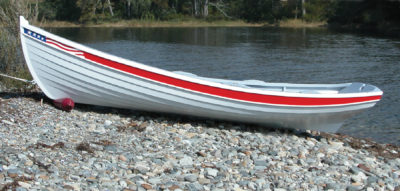

Boats don’t always need to have pointy forward ends. Here we have two easily built, square-ended workhorses that will handle all sorts of waterfront chores—and look just fine while they’re about it. Designed by Maine boatbuilder Doug Hylan, the 15′ 9″ and 19′ 0″ Ben Garveys will earn their wages.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzDesigner-builder Doug Hylan and his daughter head out across the Benjamin River in his Ben Garvey. The stable boat is easily built with plywood and epoxy, and requires only modest power.

During the 19th century, garveys evolved as modified scows (square-ended boats) on the paper-thin waters of southern New Jersey’s coastal lagoons and bays. Because these boats were meant to be rowed and/or sailed, their flat bottoms curved upward back aft to clear their runs and make for easier propulsion at low speeds and/or while carrying heavy loads. The hulls’ sides flared outward, almost in dory fashion. In all, these early garveys showed considerable shape; they were mighty handsome, as scows go.

By the middle of the 20th century, garveys had changed to accept the substantial, predictable, and noisy power supplied by internal-combustion engines (inboard and outboard). The newer boats generally showed more breadth than their ancestors, and their bottoms ran aftalmost in straight lines to the sterns. This configuration allowed them to “plane” readily—that is, to skip across the water like shingles at relatively high speeds. Their bow transoms had disappeared, and the hulls’ bottoms swept up forward all the way to the rails at deck level.

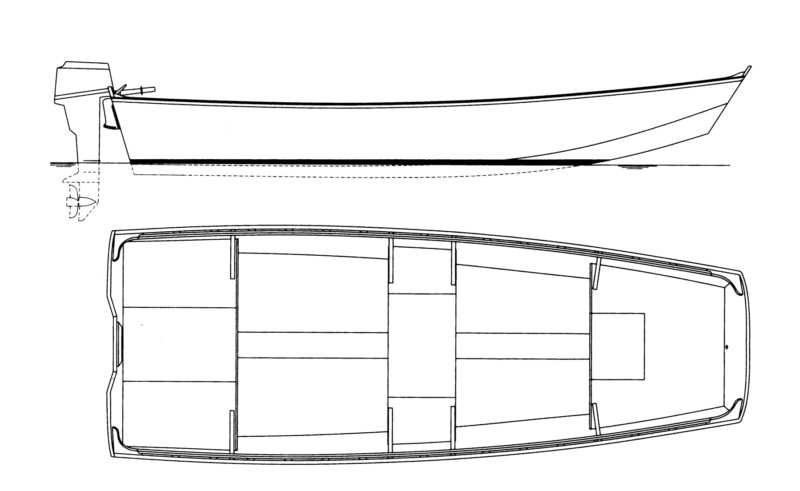

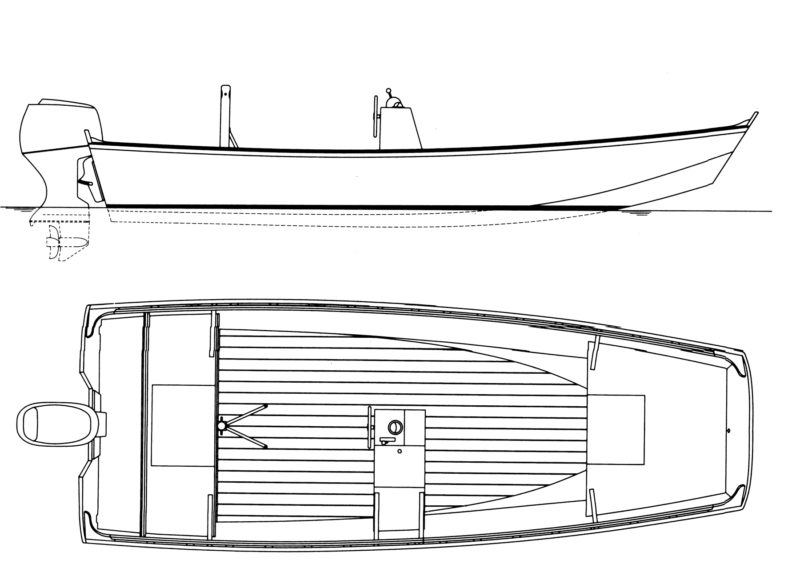

While drawing the Ben Garveys, designer Hylan looked to the future and to the past. He specified modern, perpetually leak-free plywood-and-epoxy construction; but he resurrected the bow transoms, greater flare, and stronger sheer (profile curve to the upper edges of the hulls’ sides) of the old boats.

Photo by Doug Hylan

Photo by Doug HylanThis Ben Garvey has its outboard motor mounted in an inboard well. Designer Hylan lobbies against building that well for general use as it reduces the boat’s efficiency, occupies space, and adds construction time.

Unlike many garveys, Hylan’s boats show some deadrise (V-shape) to their bottoms, and that deadrise increases as the bottoms sweep forward in gentle curves to meet the bow transoms. Deadrise adds complexity, but it gives advantages in structure and performance. For similar hulls with comparable scantlings (dimensions of structural members), V-bottomed boats tend to be more rigid than their flat-bottomed cousins. A V-bottomed hull likely will provide a smoother ride in a moderate chop and more predictable handling at speed.

A few years back, I borrowed a Ben Garvey in order to scoot across the Benjamin River for a visit with a large ketch. The spring tide was running close to high on a full moon, which allowed the fading sea breeze to push onefoot-tall waves across the bar near the river’s mouth. Riding on an easy plane, little Ben worked smoothly through this harbor chop and left behind only a barely perceptible wake. As we turned to circle the big sailboat at a respectful distance, the light garvey banked like a wellpiloted aircraft and went where she was pointed. Her ancestors were not always so well behaved. They pounded when traveling fast across anything taller than a ripple, and their flat bottoms often skidded through highspeed turns. If driven too fast with the tillers hard over, they sometimes “tripped” (capsized rapidly toward the outside of the turn). Compared to the old boats, the Ben Garvey’s handling is comfortably predictable and reassuring.

Photo by Bill Thomas

Photo by Bill Thomas“They can perform every manner of waterfront task with easy competence and honest grace.”

Doesn’t that forward transom slap and pound? Well, yes, if we push too hard and fast into steep and tall waves. Ben is no press-on-regardless ocean racer, but with the throttle eased she’ll punch along well enough. We should note that even the pointiest of pointy-bowed boats of this length, no matter their design, cannot blast to windward in all weather. When running off (that is, traveling in the same direction as wind and waves), a course that causes some pointy-bowed boats to root and otherwise act up, Ben’s manners are impeccable. In fact, Ben’s square front-end offers some advantages. It gives the spunky little boat greater stability and volume. Many a dockside capsize occurs when someone stands tall on the short foredeck of a lightly loaded, pointy nosed skiff. The hull’s sharp and narrow forefoot sinks deep into the water, and its after end lifts clear of the water. The resulting geometry is obvious, and inversion is close to inevitable. With Ben’s greater bearing and buoyancy forward, she will tolerate our exiting over the bow. If we run her up to a sandy beach head-first, the broad overhanging bow will let us step ashore dry-shod.

Photo by Bill Thomas

Photo by Bill ThomasDenny Robertson, a Maine waterman, built a house way aft on his 19′ Big Ben Garvey. The boat ferries people and supplies to an island camp in Blue Hill Bay.

We’ll build the Ben Garvey using plywood planking, epoxy-fiberglass taped seams, plywood bulkheads, and traditional structure (such as quarter knees, which connect the sides and transom). The hull goes together upside down over temporary molds on a ladder frame. This project offers an education to beginners or will go together quickly with experienced hands. In either case, the results should be light, strong, and tight. Unlike traditional plank-on-frame boats, a Ben Garvey will live happily on her trailer. She won’t leak when first put in the water or suffer structural damage if driven hard too soon after launching. Should the worst happen, built-in flotation compartments will keep the expensive motor’s head above the water.

As the drawings suggest, little Ben’s layout is plain as can be. We’ll steer from the stern seat by grabbing hold of the motor’s tiller—simple, direct, inexpensive. For Big Ben, the plans tell us to build a console amidships, which we’ll rig with remote controls and perhaps some electronic navigation paraphernalia.

Photo by Mike O'Connell

Photo by Mike O'ConnellMike O’Connell built this center-console Big Ben. The husky boat earns its keep by assisting rowing crews near Pittsburgh and working for the local Riverkeepers.

To ensure reliable power and to reduce pollution, we’ll hang a four-stroke outboard motor on the transom of our Ben Garvey. Designer Hylan suggests a 15-hp to 35-hp engine for little Ben and 25–85 hp for Big Ben. Talking about the larger boat, he adds: “Unless frequent heavy load is anticipated, 40 hp will be adequate.” The plans for the smaller garvey show a motorwell option, which would allow us to install our outboard motor inboard. But Ben’s creator lobbies against our building that well:

“For general use, this version is not recommended as it reduces planing efficiency, has less usable space and allowable capacity, and is more difficult to build.”

Boats that are similar to each other tend to increase in “size” approximately as the cube of their lengths. Big Ben, at 19′ 6′ 11″, is not simply 3′ 3″ longer than the 15′ 9″ 5′ 7″ Ben. Indeed, she is huge by comparison. Denny Robertson, a Maine coast waterman, made good use of that extra volume and capacity by building a small house way aft on his 19-footer, BERT FRIEND. Powered by a 90-hp Johnson outboard motor, that boat carries supplies and gear, including small vehicles, to an island camp in Blue Hill Bay. Another Big Ben tends to the needs of rowing crews near Pittsburgh and works for the local Riverkeepers.

Built as drawn, these Ben Garveys are tough boats that will be at home in almost any harbor. Boatyard chores, harbor ferrying, recreational fishing, entry-level lobstering or shellfish harvesting…. They can perform every manner of waterfront task with easy competence and honest grace.

Ready to Build Your Own Ben Garvey?

The Ben Garvey design is easily built with plywood and epoxy, and requires only modest power. Review our study guide for the Ben Garveys, then find plans for the 15′9″ and 19′ designs at the WoodenBoat Store.

Ben Garvey Particulars

[table]

LOA: 15’9″

LWL: 11’9″

Beam: 5’7″

Draft: 4″

Displacement: 460lbs

Power: 15-35hp

[/table]

The Ben Garvey

Big Ben Garvey Particulars

[table]

LOA: 19′

LWL: 14’3″

Beam: 6’11”

Draft: 6″

Displacement: 810lbs

Power: 25-85hp

[/table]

The Big Ben Garvey

Plans for the Ben Garvey and Big Ben are available at The WoodenBoat Store

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Nice revived interest in the garveys. Had a fun 15′ Jersey-built one, with 25 hp in the late ’50s. Was even a racing bunch active then. Handy little craft.

The March/April 1998 issue of Boatbuilder has a plan for a nice 20′ X 6’3″ garvey. It also has a V bottom, is built of plywood, and has a center console. Looks like a good boat. That design is by Dave Gerr.

As for the tendency to pound, I rode on Puget Sound waters in a good size garvey that belonged to the Washington State DNR and was used for tending marine parks in the northern PS region. We made good speed (18 to 20 knots, maybe) over a fairly lumpy chop, and the ride was surprisingly smooth, especially compared to other boats I’d been on, such as a 17′ cruiser (name of which I can’t remember) that gave a very harsh ride over a 4″ ripple. I’m not sure how long that garvey was, but we were able to carry 2 or 3 kayaks 16′ to 17′ long aboard. It also had the aft pilot house.

I’m thinking I’ve got one more boat build in me and the Garvey could well be the one. I have been leaning heavily towards the Atkin’s Ninigret for a number of reasons, not least of which is motor in a well that is protected from waves over the transom. Many otherwise fine power boats have gone down because the motor conked out in a storm, the boat weathercocked facing downwind and took one too many over the stern.

So I’m wondering if the Garvey could have some kind of protection added back there for that potential event? And maybe a bit higher freeboard for that feeling of safety even if it’s never really put to the test?