Skimming across Copper Harbor, the Manitou 18 summons memories of lazy summer days in the 1950s on waterfronts across America. Built for coastal running on the Great Lakes and the region’s large inland waters, the eye-catching runabout—18′ LOA, with a 6′ 7″ beam—features a deep-V hull, substantial deadrise, and a sweeping sheer. Based on the Downeaster 18 by Charles W. Wittholz, the boat is a contemporary rendition by Copper Harbor Boat Works, a small shop on the tip of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, which juts into Lake Superior.

After building two small runabouts, the Boat Works sought a design that was better suited for the often choppy waters along the Lake Superior shoreline. Research led the shop’s founder, Ray Chamberlain, to the Wittholz runabout. In 1986, WoodenBoat Publications commissioned Graham Ero to build a Downeaster 18 (see WB Nos. 73, 74, and 75). Contacting Ero in Still Pond, Maryland, Copper Harbor boatwright Jeff Coltas inquired about the boat’s performance and solicited suggestions regarding its construction. Satisfied with the design and Ero’s feedback, Chamberlain decided to move ahead with the Manitou 18 project.

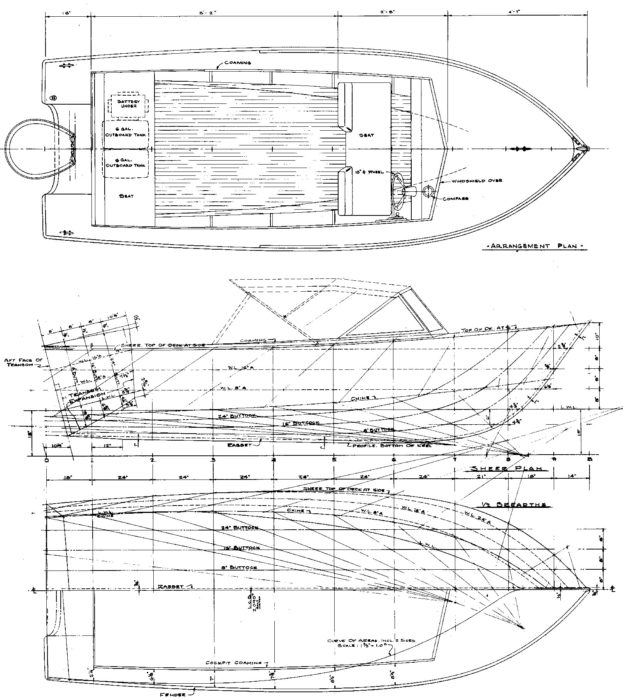

On a blustery midwinter day, with snow swirling in the north woods near the Lake Superior shore, the three-man crew commenced lofting the Manitou 18 in the shop’s snug confines, a small barn warmed by a fire crackling in the wood-burning stove. Lofting proved to be the most difficult step in the process, according to Chamberlain. The plans contained a table of offsets, but no patterns, requiring full-sized plywood templates to be fully developed for each part. While working straight from offsets may seem daunting to some, a builder with intermediate skills or an amateur who is very dedicated can build this boat. Of course, familiarity with lofting is also a good idea.

George D. Jepson

George D. JepsonA storage compartment separates the two stern seats providing space for the fuel tank.

With Wittholz’s plans to guide them, the team began the hull’s plank-on-frame construction. Frames sawn from 3⁄4″ marine plywood and secured to the strongback hinted at the hull’s eventual shape. The frames were paired with pieces of red oak, providing a better surface on which to fasten the planks. The builders cut the 13⁄8″ keel and the keelson from mahogany, the stem from ash, and the sternpost from red oak. While white oak is generally accepted as a better boatbuilding wood than red oak, because of red oak’s known porousness, Chamberlain reasoned that encapsulating the wood in epoxy should provide sufficient protection against decay. Some builders will feel safer using white oak instead. They laminated two layers of 3⁄4″ mahogany plywood to form the transom.

Coltas reported that the Downeaster 18’s hull had a tendency to flex with the 9mm plywood planks specified in the plans. To strengthen the hull, the crew added one more frame and hung thicker, 12mm okoume side and bottom planks. Two additional Sitka-spruce stringers—six in total—further stiffened the bottom. Turning the hull upright, they noticed that the bow was a little high, but Coltas and crew liked the look, so rather than cutting it back they simply put a little more sweep in the sheer than was called for in the plans.

George D. Jepson

George D. JepsonThe runabout handles Lake Superior nicely, providing a dry, comfortable ride.

Once work began on the interior, the builders adjusted the seating plan. Moving the forward bench aft a few inches provided greater legroom and comfort for the helmsman and a passenger. Two stern seats, separated by a storage cabinet, completed the arrangement. Outboard fuel tanks are stored under the seats, which were fabricated from mahogany plywood. Most internal parts, including the seats, are fastened with stainless-steel screws, making them easy to remove. The sole is attached with bronze screws. This simple helm-forward plan provides ample space and storage for one to six on a daylong cruise.

The Manitou 18’s elegant interior and decking are among its most stunning features. Pinstriped fore and aft decks, built with 1⁄4″ bird’s-eye maple over 6mm okoume, add to the boat’s charm. The builders made the ceiling from quartersawn red oak and the sole from black walnut and red oak, and framed the windshield in maple.

The Boat Works sealed everything in epoxy before finishing, and paid careful attention to details when they applied the finish. They gave the entire boat—inside and out—two to three coats of clear epoxy, then painted the topsides with four coats of pale yellow, two-part polyurethane. Below the waterline, they applied four coats of white Teflon bottom paint. Interior surfaces and the decks were finished bright, with at least five coats of varnish. The team expended over 700 hours on this project.

In addition to the helm-forward layout, the boat is also available with a center-console configuration. The versa tile design accommodates multiple power options. This particular boat is driven by a 90-hp Evinrude E-Tec outboard, but was designed for 40- to 100-hp outboard motors. Other alternatives include an inboard/outboard or jet drive, as well as an inboard engine. Instrumentation includes a speedometer, tachometer, fuel gauge, and ammeter.

The seating and propulsion options will meet a variety of boating needs, from coastal cruising to pulling water skiers to picking up groceries at the local marina market. Easily trailered and simple to launch at public ramps, the Manitou 18 can be kept dry and under cover on its custom trailer—a good idea for any fine boat—or moored in front of the family cottage.

George D. Jepson

George D. JepsonThe Manitou’s attractive lines should earn some second looks at the launching ramp.

On a late-summer morning, I drove northeast on U.S. 41 toward Copper Harbor, a small, picturesque town. Under a brilliant clear-blue sky trees already displayed splashes of color, a sure sign that the boating season on Superior—called the “Big Lake” by those living near its shores—was nearing an end. At Copper Harbor Boat Works, the Manitou 18 sat on her trailer near the boat ramp. Less than five minutes after I saw her, she slid into the crystal water, reflecting her lustrous natural woods under the northern sun.

This is a charming little showboat, displaying impeccable workmanship from stem to stern. Chamberlain chose to trim the Manitou 18 with these special woods and the bright finish, but, in my opinion, she would also look comely with less brightwork and a painted finish. The latter option would hold up better against heavy use, too.

As we stepped aboard the runabout at the Boat Works dock, a light zephyr rippled across the water’s surface. Otherwise, all was still in the vast harbor, which stretches for nearly 3 miles and opens into Lake Superior. The Manitou 18’s chrome wheel and steering knob are throwbacks to the days of rock-and-roll and hot wheels, from customized roadsters to the early muscle cars, and reflect Chamberlain’s passions for speed and music with a classic ’50s beat.

As I edged the throttle forward, the boat literally flew over the water, streaming a clean wake. Momentarily, my mind drifted back to the late ’50s and early ’60s. Strains of Doo Wop tunes played in my subconscious, recalling endless summers on the water, pulling skiers or cruising along the beach. I was at the wheel of our old family runabout again, with the wind in my hair and Superior’s blue water spread before me.

The ride was smooth, even as we approached 40 mph. The boat and motor were relatively quiet. Powering into turns, the Manitou 18 responded with ease. As we accelerated on the straightaway, the stern barely squatted and the boat once again rose up on plane. It sliced through a building chop with minimal buffeting. At cruising speeds, the Manitou 18 is level and balanced. Chamberlain plans to add trim tabs to further balance the relatively light boat when there is just one person aboard.

Conditions were nearly perfect on this day, hardly challenging the Manitou’s capabilities. During earlier sea trials, the boat proved her mettle, powering through 2′ to 3′ seas in Lake Superior with her V-bow. The boat’s narrow entry makes her a bit tender side-to-side, but that’s the trade off we make for speed. The runabout is well suited for coastal waterways, whether fresh or salty. She handles Lake Superior nicely, providing a dry, comfortable ride.

George D. Jepson

George D. JepsonThe Manitou is rated for 40- to 100-hp outboard motors. With a 90-hp Evinrude E-Tec outboard, she flew across the water, giving a smooth ride at speeds up to 40 mph.

Overall, the Manitou 18 is simple to operate and is roomy enough to fit two additional seats just aft of the forward bench seats. Custom-made seat and back cushions give added creature comfort to the helmsman and passengers. Storage cabinets behind the forward seats are handy and suitable for towels or extra gear, such as binoculars. The boat is an extremely versatile modern classic, offering years of enjoyment with minimal maintenance.

Whether viewing the Manitou 18 moored dockside or sweeping through a sharp turn, boaters with a touch of gray will recall the time a half century ago when vintage wooden runabouts turned heads on waterfronts from coast to coast.![]()

Plans for the Downeaster 18 can be ordered from The WoodenBoat Store.

Copper Harbor Boat Works is no longer in business.

These plans by Charles Wittholz appeared in WoodenBoat No. 73 as the first part of a three-part article by Graham Ero called “Building the Downeaster 18.” Copper Harbor’s modifications included raising the sheerline at the bow, using 12mm planking, and installing two additional stringers and one more frame. Particulars: LOA 18′, Beam 6’7″, Draft 1’1 1/2″, Displacement 1765 lbs (dry), Power 40-100 hp

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.