Lukas Schwimann’s home is in the village of St. Gilgen, Austria, at the top end of Lake Wolfgang—Wolfgangsee in German. A friend who lives near him owns a 16′5″ rowing skiff that has been in his family for about 100 years. The boat is not in great condition, but it is still serviceable. Over the years it has been patched up with chopped-strand mat and polyester resin. Lukas has had several opportunities to use it and has found it to be an enjoyable boat to row. He already has three sailboats, and his wife, Irmfried, insisted that if he were going to attend the Boat Building Academy at Lyme Regis and build a boat there, it would have to be a rowing boat. Lukas decided he would build a replica of the skiff.

Lukas Schwimann

Lukas SchwimannNew and old: the reproduction, here rowed tandem, has the same flat sheer as the original skiff behind it.

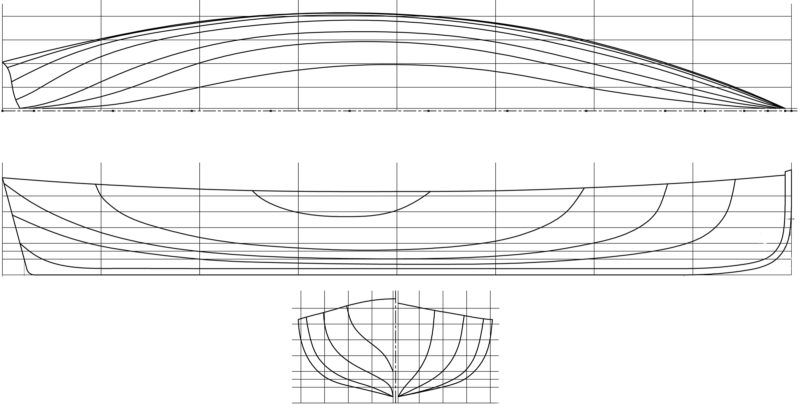

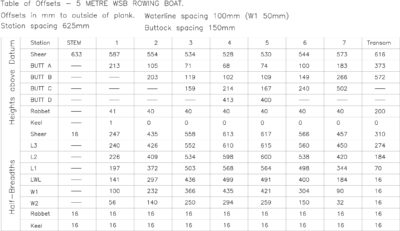

Lukas’s starting point was to take the lines off the old boat, although this proved particularly difficult as its shape had distorted somewhat over the years. “It was kind of hogged and sagged all at the same time,” said course tutor Mike Broome. When Lukas arrived at the Academy, he gave Mike the information he had. “It was a bit like a fairground ride,” said Mike, “but I breathed on it a bit with CAD and produced a table of offsets.” From this, Lukas and his fellow students lofted the boat full size and then “tweaked it here and there.”

Despite the distortion in the original boat, Lukas recognized that it had a fairly straight sheer and that was one characteristic that he was keen to retain. Although it is thought that it was originally used as a leisure boat, Lukas thinks it is a “workboat type and doesn’t have any fancy features” and he was also keen to replicate that. When he measured the skiff’s scantlings he kept coming across the figure of 44mm (1-3/4″) or neat divisions of it and used that as a guide through the lofting details.

Nigel Sharp

Nigel SharpThe cleats below the oarlocks have a hole to brace the bottom ends of the oarlocks and to slow the wear on the sockets. The feature was built into the original boat. Removable, adjustable heel braces anchor the rowers.

The boat was built upright, and before construction could begin, a strongback was set up with its top about 2′ off the workshop floor, and directly below an overhead beam. These were put in place with great care and accuracy—partly with the aid of a laser—to ensure the centerline components would be exactly in line. Assembly of the boat’s sapele backbone components could then proceed, beginning with the perfectly straight keel (1-3/4″ thick at its maximum) and hog (3 1/2″ x 7/8″). The stem was composed of a grown outer part in two sections scarfed together and with the lower section scarfed to the keel and hog; and an inner part, or apron, which was laminated from 11 layers to give a thickness of 1-3/4″ and which overlapped the top of the hog over a length of 16″. The 7/8″-thick sapele transom was supported by a 1-3/4″-thick sapele stern knee. All of the centerline components were glued together with epoxy and fastened with bronze screws.

The seven plywood molds produced from the lofting were temporarily fastened to the hog and braced with cross spalls and struts going up to the overhead beam. Battens secured to the stem head and cross-spalls held the molds in their vertical positions.

Lining off the eight strakes was done with a 13/16″ x 1/4″ batten, the same width as the planking laps. The rabbets for the planking had been cut into the keel, hog, and stem as part of the lofting process and had now been faired, so with the laps marked on the stem, molds, and transom, now everything was ready to fit the 3/8″-thick khaya planking. The garboards were dry-fitted, checked for accuracy, and then permanently installed with silicon bronze screws and butyl rubber mastic as a sealant.

The rest of the planks followed, riveted together at the lapse with copper rivets spaced at 2-5/8″ intervals, skipping where the steam-bent frames would be installed later and fastened with longer rivets. All of the planks needed some steaming to cope with the twist at both ends of the boat. Lukas found the mastic “messy to work with and I am not sure if it was necessary apart from with the garboards and the hood ends. The garboards are obviously a critical element and as they were the first planks we fitted, we were learning fast then, so I am glad to have mastic there.”

Lukas Schwimann

Lukas SchwimannThe solo rower can choose between the two rowing stations, aft for downwind work, forward for rowing to windward.

The molds and their supporting struts were removed, leaving struts from the transom and stem to the roof beam, and adding two new temporary braces across the boat and notched over the sheerstrake.

Oak frames, milled to 7/8″ x 7/16″ and tapered to 5/16″ at the ends, were steamed into place at 8″ spacings and riveted to the planking. They were continuous from one side of the boat to the other, except for the forwardmost three, which were taken down to the outer faces of the apron, and the aftermost two, which were taken down to the top of the hog where the garboards are nearly vertical. The framing started amidships and worked toward the ends. A few of the amidships frames broke as they were being fitted, and a piece of that was used to make a shorter rib at one end of the boat.

After the frames were installed, their ends were cut a little below the sheer. The sapele inwale was notched to fit over the frame heads, then steam-bent into place. Mastic sealed the frames’ end-grain. The sapele outwale was not steamed but left overlength initially to help with the bending. The finished gunwale, perhaps not surprisingly, has an overall gunwale thickness of the “magic” 1 3/4″.

Ten 7/8″-thick sapele floor timbers were fastened with bronze screws through the planking. The 1/2″ khaya floorboards bear on the structural floors; both rowing positions have adjustable stretchers. The khaya thwarts had individual end supports rather than full-length risers. The sapele breasthook, transom quarter knees, and thwart knees were each made from two pieces with a half-lap joint between them.

Part of the course at the Academy involves making spars and oars, and Lukas managed to persuade three other students to make oars in the same size and style as the one he’d made in spruce with a sapele inlay, giving him a matching set of four oars.

Lukas Schwimann

Lukas SchwimannWith two rowing, the bow trims well when the rowers lean aft at the catch. When their weight moves forward at the release, the bow dips a bit.

A long time ago, I spent several years sculling and rowing competitively in everything from single sculls to eights on various English rivers, and I have always enjoyed rowing my own yacht tender. With Lukas happily leaning against the transom keeping watch forward, I took the bow rowing seat in his newly launched Wolfgangsee skiff. A fellow student, Will Mackie, set the pace from the stern station. The boat felt like the best of all compromises. It was more stable than a river-racing boat, of course, but at the same time considerably faster and easier to row than the average yacht tender; it really was a joy.

There was practically no wind, so we were lucky enough to enjoy flat water, but even the wash of a passing speedboat did little to concern us. The new boat has a beam of 4’ and the oars are 8’ long, proportions that felt just right, as did the relative heights and fore-and-aft positions of the seats and rowlocks.

Nigel Sharp

Nigel SharpWith the builder rowing in the stroke position, the skiff carries a passenger without sousing the stern.

On its home waters in Austria, Lukas was able to report further on its performance. “Interestingly enough there is not much difference in the speed with one or two rowers,” he said. “The maximum speed is somewhere between 6.3 and 6.8 knots, and it depends more on the wind and waves. When crossing the lake with some side wind you feel the boat going off to one side, as is to be expected, but it can easily be compensated when pulling a few strokes stronger on one side. To turn the boat, by pulling with one oar and pushing with the other, it takes about four strokes to turn around. It is also interesting how the boat sits in the water: it is best with either one rower or with two rowers and a passenger. With two at the oars and no passenger, the bow dips a little bit with the rowers’ layback at the finish of the stroke.”

Irmfried is particularly keen to use the boat to row across Wolfgangsee to their favorite restaurant. Lukas plans to set up as a boatbuilder and he is very much hoping that the original boat’s owners, when they see his reproduction of it, will be eager to have him build a new one for them.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry, and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Wolfgangsee Skiff Particulars

[table]

Length/16′5″

Beam 48.8″

Depth amidships/20.75″

[/table]

For more information about the Wolfgangsee skiff, email Mike Broome at the Boat Building Academy, or the builder, Lukas Schwimann.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Hello,

Beautiful boat. Was the Sapele stained, or is that the natural colour? Loving how yours glows. I’m currently doing research on how to finish Sapele planking on the deck of new build.