The Fine is a cedar-strip sliding-seat pulling boat designed and built by Rick Crook of Madeira Park, British Columbia. He describes it as “a full-body workout machine. The Fine is wider than a rowing scull, thus more stable, and is suitable for ocean rowing, in reasonable conditions.”

Rick does business as Oyster Bay Boats, specializes in cedar-strip construction, and builds double-paddle canoes and rowboats. He finishes many of his boats bright and takes care to ensure the wood beneath the varnish looks good.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorBoth the outriggers and sliding seat unit can be easily removed to lighten the Fine for cartopping and carrying across the beach to and from the water.

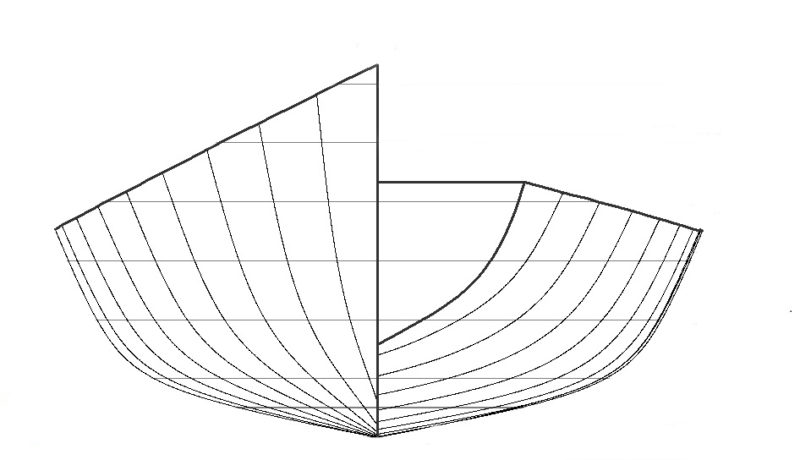

During the Fine’s construction, as with all Oyster Bay boats, its red and yellow cedar strips are glued to one another and held in place with stretchy nylon monofilament rather than staples so there are no rows of dark spots that staples leave behind. The hull is sheathed inside and out with 4-oz ’glass cloth and biobased epoxy. The gunwales are big-leaf maple. The foredeck and recessed aft deck are supported by bulkheads, and access to the resulting enclosed flotation chambers is through deck plates.

A keel runs almost the full length of the hull and provides tracking as well as protection for the hull when it’s hauled on the beach. It ends in a skeg at the stern and is topped by a transom that sits well above the waterline. The weight of the hull, without the rowing rig, is around 65 lbs (not much more than a sea kayak) and is well suited to roof-rack transport.

The Fine’s outriggers and sliding seat can be moved forward from the standard rowing position to accommodate a passenger sitting in the aft end of the cockpit.

The sliding-seat arrangement is a wooden drop-in unit with weight-reducing cutouts. Aluminum tracks support a sliding seat with ball-bearing-equipped nylon wheels. Two 1⁄4″ machine screws secure the seat unit to cleats built into the hull and it can be moved forward from its normal position to accommodate the weight of a passenger carried in the stern. At the aft end of the unit, wooden clogs with heel cups and Velcro straps provide solid bracing for the feet. The outriggers are made of aluminum and held in place on the gunwale by quick-release clamps that engage aluminum plates slipped in place under the gunwale. The outriggers support gated racing-shell oarlocks.

The Fine’s stability makes it easy for the rower to launch from almost anywhere and get aboard once it’s afloat rather than having to find a floating dock low enough to clear the outriggers.

While the Fine was already at the beach when I arrived for sea trials, the bare hull, at 65 lbs, would be a heavy shoulder carry but manageable for short distances. A cart would be the most practical way to get the boat and the rowing rig in one haul from a parking lot to the water’s edge.

As I stepped aboard the Fine, afloat in the shallow water, it had more than enough stability to support me and stay upright as I brought my weight over the gunwale. Once I was seated, the initial stability was very good and didn’t require the help of the oars to put me at ease. I leaned on the gunwale and the secondary stiffened up reassuringly, even as the sheerline dipped within 1″ of the water.

With designer and builder Rick Crook at the oars, the Fine slips along at a good clip, leaving nearly smooth water in its wake.

The clogs are set at a comfortable angle, and I could keep my heels planted in them when I moved to the aft end of the slide for the catch. I’m 6′ tall, and the tracks extended 10″ farther aft than I needed; shorter rowers will have plenty of room on the slide. At the finish of the stroke, I had just enough room at the forward end of the tracks to avoid hitting the stops; taller rowers may need a longer sliding-seat frame.

I got underway with the carbon hatchet sculls provided by Oyster Bay Boats. The height of the seat and the riggers was right on the mark for me: at the finish of the stroke, the handles were even with the bottom of my sternum. In the middle of the recovery, the handles had a 4″ overlap, which gave me the hand-over-hand position I’m used to. The Fine has excellent tracking, and I didn’t need to keep my gaze over the transom to make adjustments to keep on course. Turning is a little stiff—it took 12 1⁄2 strokes to spin through 360 degrees—but appropriate for a boat meant for aerobic exercise and passagemaking.

The Fine’s full-length keel and deep skeg give it excellent tracking.

Measuring speed with a GPS while I was rowing in water protected from wind and current, I could maintain 4 knots with ease and an exercise pace brought the Fine up to 5 1⁄2 knots. It was hard to get a good reading on the GPS in a short all-out sprint as the numbers on the display fluctuated when the boat accelerated as I moved aft at the recovery and then slowed as I moved toward the bow, pushing the boat back, at the drive. The readings averaged out at about 7 knots—the Fine is a fast boat for its size. During the sprints, when I was pulling hard, I didn’t feel any flexing of the outrigger.

Many fast sliding-seat boats with outriggers rely on their oars for stability. The Fine’s 34″-wide hull has enough inherent stability to allow the rower to take a break from holding the oars.

When I finished my rowing trials, I stopped in about 6′ of water to do a capsize drill. I pivoted the port oar parallel to the Fine and leaned over the gunwale. It took a lot of effort to get the boat up on edge, and I fell out before it turned turtle. The boat flopped back on an even keel, and I was able to crawl back on board over the side without any concern that the Fine would roll over on top of me. It stayed upright, and once I was back aboard I could move about in the swamped cockpit without feeling unstable and make my way back to the rowing station.

The seat had floated off the tracks, and it was difficult to get it back in place and then sit on it to keep it from floating off again. Sitting on the tracks was painful and put me too low to row effectively, so I had to get the seat back where it belonged, in its tracks. The tracks have flanges that are meant to engage retaining clips on the sliding seat to avoid this situation. The seat should be outfitted with those clips.

Rick Crook

Rick CrookEven when fully swamped after an intentional capsize, the author could still easily row the Fine, albeit slowly.

Once I got the seat on the tracks and pinned it there by sitting on it, I was able to row. The Fine floated with the gunwales just awash amidships, so bailing would have been futile, but I was mobile. After I rowed around just to see how the boat moved and maneuvered when full of water, I returned to the beach, where I had some help getting the water out. It was discovered that the stern compartment had a lot of water in it. The deck plate may have been loose. If the Fine had had the full benefit of its buoyancy compartments, there may have been a better chance of bailing it out after I’d climbed back aboard.

Rick has built Fines for several customers, and photographs of those boats show decks of different lengths to suit the needs of their owners. Opting for sealed-end compartments with more volume would be prudent for rowers intending to take on challenging conditions. A smaller stern compartment with a longer open cockpit would provide room for taking a passenger out in pleasant conditions. With large access ports on top of the compartments, gear could be safely stowed. The open gunwales provide convenient places to secure any gear stowed in the open cockpit. I didn’t row the Fine with cargo aboard, but a photo of one being rowed with a passenger seated in the stern shows that the boat can take the additional weight of a companion or cruising cargo without giving up too much freeboard or dragging its transom through the water.

Sliding seats and outriggers are often associated with slender hulls designed for speed at the expense of stability, but the Fine combines that rowing rig with a hull that can take care of itself and allow the rower to enjoy full-body exercise and still take in the scenery whether it’s drifting by at a snail’s pace or zipping past at 7 knots.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine.

Fine Particulars

Length: 18′

Beam: 34″

Weight, without riggers and sliding seat: 65 lbs

The Fine is available from Oyster Bay Boats as a finished boat, built to order, for $6,800 CAD. Carbon-composite oars are included.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.