Boat nuts of a certain age still shiver with pleasure at the recollection of perky technicolor blondes in old Chris-Craft ads. A generation of boomers learned how to water-ski behind varnished runabouts, and these days they turn out at classic boat shows in big numbers to admire the restored beauties.

Already a monumental success in 1950, Chris-Craft thought to use up their mountain of mahogany scrap by cutting kits for handsome plywood power skiffs. It must have been some mountain; Chris-Craft claims that between 1950 and 1958 they shipped 93,000 boat kits in 13 different models sized from 8′ to 31′.

There’s only so much patience and money in the world for major restorations, and the pool of restorable Chris-Crafts is dwindling. Meanwhile, the people who grew up in mahogany runabouts are at retirement age and casting about for affordable projects. Captain Jim Shotwell, boatbuilder and activist member of the Antique & Classic Boat Society, sought to breed a new generation of classics by reviving the Chris-Craft kits of the 1950s.

Photo courtesy of James Craft Marine Services

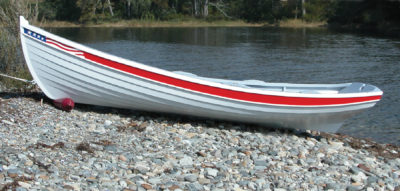

Photo courtesy of James Craft Marine ServicesJames Craft Marine Services offers reproductions of the highly regarded Chris-Craft kit boats from the 1950s. The single-cockpit Comet GR is a “Gentleman’s Racer.”

Shotwell tracked down two 1950s Chris-Craft kits in the garage of a New Jersey yacht broker, still in the original packing crates. Research at museums and reverse engineering of completed Chris-Craft kits ultimately gave him a catalog of 12 kits from 8′ to 16′. He obtained permission from Chris-Craft to reproduce the designs, and set up a company called James Craft at his Nescopeck, Pennsylvania, shop on the banks of the Susquehanna River. So authentic are his kits that the Antique & Classic Boat Society accepts finished James Craft kits as “contemporary reproductions” for competition judging.

A 14-footer is one of Shotwell’s most popular models, and like the originals it’s available with several deck schemes. There’s a utilitarian open hull, the Dolphin, meant to be steered with the outboard’s tiller, and suited to fishing. Two decked-in versions, the Hornet and Zephyr, have wheel steering and speedboat styling, and look especially smart.

The Zephyr has a shapely single-chined hull with tumble-homed stern quarters, a shallow V amidships with noticeable compound curve in the sections, and as fine a bow as you can get by twisting plywood bottom panels onto a stem. Such shapes are meant for protected waters, but a 15-horse outboard (preferably a restored 1955 Evinrude) will pull a water-skier at speed.

Photo courtesy of James Craft Marine Services

Photo courtesy of James Craft Marine ServicesJames Craft Marine Services offers reproductions of the highly regarded Chris-Craft kit boats from the 1950s. The 14′ Zephyr is a double-cockpit runabout.

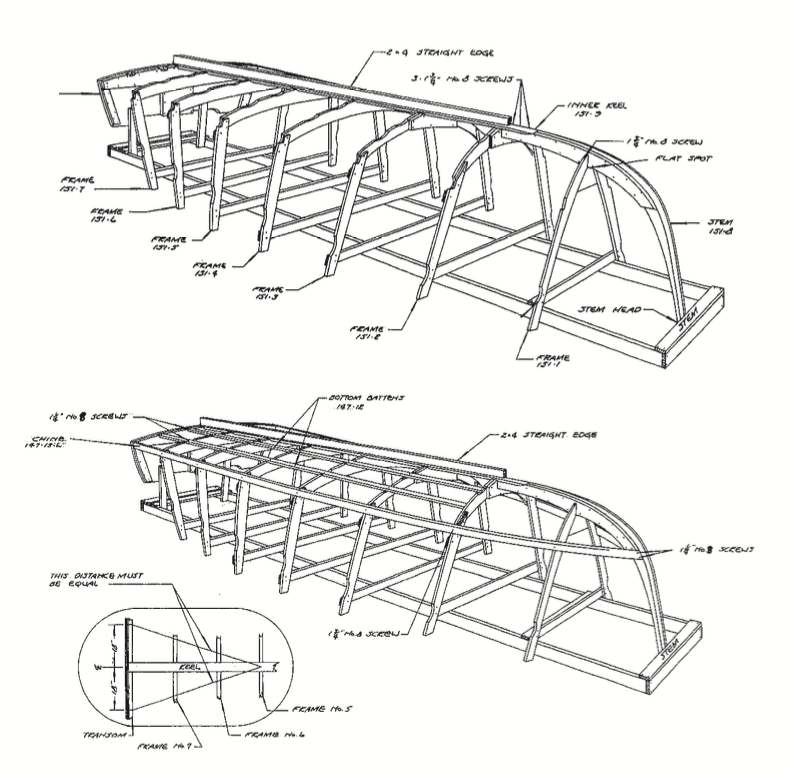

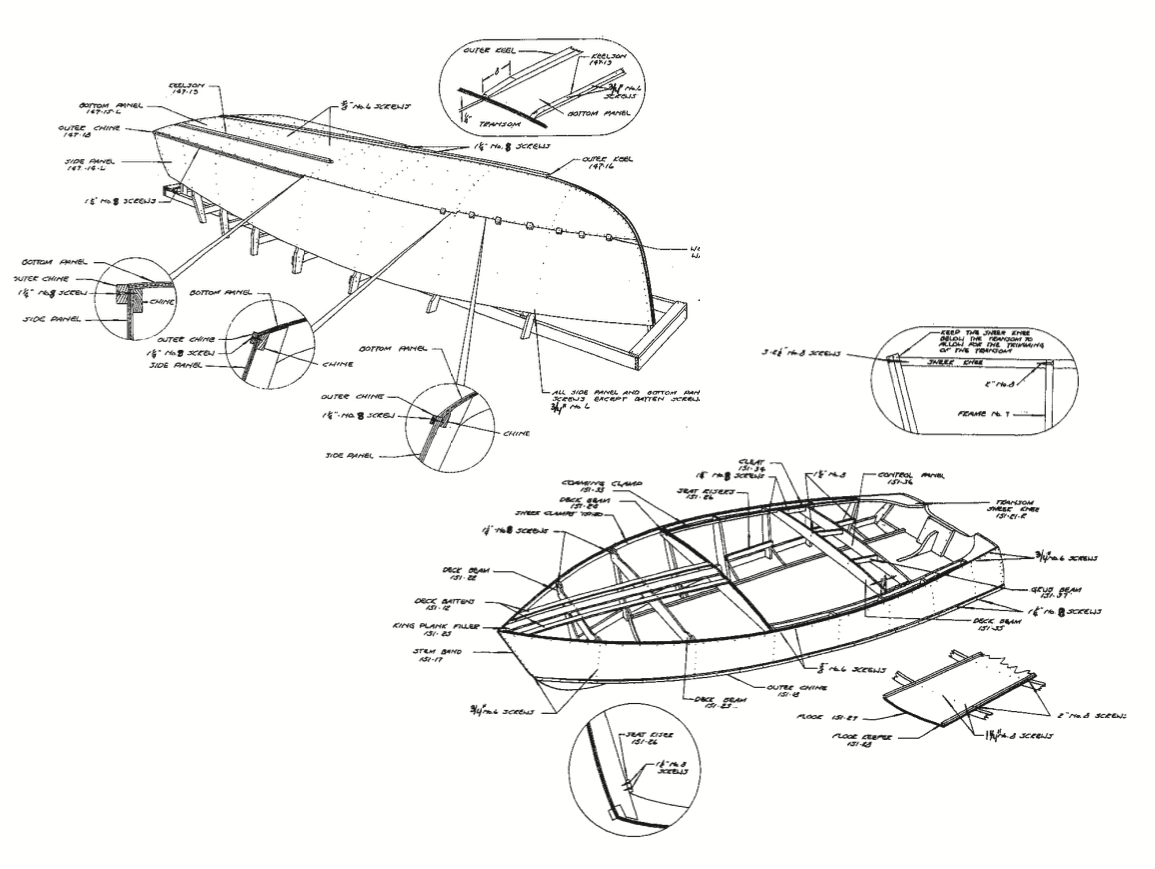

I have a huge collection of mid-century “Build Your Own Boat” publications put out by Mechanics Illustrated and Popular Mechanics. I love the beautiful inked isometric views of keels and stems and gusseted frames that, the old magazines promised, “Any weekend carpenter can build!” I wonder how much imprecation and salty language was invented by the average weekend carpenter as he beveled all of those frames and stringers. With an army of production-oriented workers at their disposal, Chris-Craft had the wherewithal to prefabricate frames and prebeveled components in their kits. The availability of a kit in which the multitude of bevels is already conquered for you must explain the staggering success of the kits at the time.

In his Pennsylvania factory, Shotwell has faithfully recreated the kits, including accurately beveled frames, stems, and knees. Frames and transoms are already glued up. Even chine logs and sheer clamps, which have rolling bevels, are machined in advance. With Shotwell’s pre-cut parts, construction techniques that were state-of-the-art in the 1950s are accessible to the average 2006 builder. All a Zephyr builder needs are a couple of 2x6s for the traditional ladder-frame building jig. Seven frames, a stem, an “inner keel,” and transom are set up on the jig within an hour or two of opening the box. Frames are made of fir, as are the numerous stringers. Bronze screws are used throughout construction.

Photo courtesy of James Craft Marine Services

Photo courtesy of James Craft Marine ServicesThe box the boat comes in contains beveled frames, which save the builder time and ensure accurate fit.

The plywood hull panels are cut to shape but will require trimming and beveling. Arguably the trickiest step in the entire assembly will be joining the bottom panels to the side panels. The bottom panels sit atop the side panels from the transom to about Station 2. At that point the builder cuts a jog in the panels and the lap joint becomes a butt joint. This is a neater way to build single-chined boats. The alternative is to expose as much as an inch of plywood end-grain in grinding the bottom panels smooth with the side at the bow. This challenging transition is largely ignored in modern stitch-and-glue boatbuilding but was a rite of passage for plywood boat builders for decades. It’s good to see this craftsmanlike approach back in circulation.

Photo courtesy of James Craft Marine Services

Photo courtesy of James Craft Marine ServicesIntended for amateur assembly, these kits make fine projects for youth groups.

The original Zephyr was skinned with fir marine plywood, but Shotwell has substituted okoume, or sapele for those who want a varnished hull. The high-quality marine panels of 2006 are an unqualified improvement over the originals. So are the adhesives. In 1955 the kits were assembled with Dolfinite bedding compound between parts; 6 to 10 years was the stated span in which this goo would keep the water out. Unless the planking was protected with fiberglass, or completely rebedded, your Chris-Craft kit would begin to leak, and if not maintained, it would slowly dissolve into mulch. I’m guessing that’s what happened to most of the 93,000 kits. Modern Zephyr builders will use epoxy wherever wood meets wood. So strong is the epoxy that the bronze screws are largely vestigial; Shotwell suggests that temporary drywall screws could be used to hold parts together, removed when the epoxy cures, and the holes plugged.

Hulls are sheathed on the outside with fiberglass set in epoxy. The 7.5-ounce fiberglass cloth will resist dings and abrasion and provide a hard, smooth surface for paint or varnish. If you pickle the interior of the boat with epoxy, water will never touch wood and maintenance will be reduced to near zero.

Planked mahogany decks finished with varnish are part of the iconic look of the mid-century Chris-Craft, and are included in the James Craft kits. The planked deck is supported by frames, a kingplank, and battens backing up every plank seam. Bonded with epoxy, this scheme will never leak. A covering board sawn from solid mahogany sustains the look. Staining the mahogany is the best way to achieve the even coloration beneath varnish that distinguishes a real Chris-Craft.

Builders have the option to add an authentically styled windshield to their Zephyr; the frame is produced for James Craft in chrome-plated bronze. James Craft can supply, or help you track down, other bits of period hardware to complete the nostalgic reproduction of a 1950s nautical icon.

These construction drawings from the original Chris-Craft packages are included with all James Craft kits. They describe traditional plywood construction with a robust backbone and plenty of transverse frames: light, tight, and strong. Built of better materials than the originals, the James Craft boats should outlast their predecessors.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2007 and appears here as archival material. If you have more info about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Outstanding !!!

This is the kind of boats that we “flatlanders” like.

I believe they went out of business. Too bad.