I don’t think Lao Tzu got it right when he wrote in the Tao Te Ching: “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” All my long cruises began with a daydream, an idea that captured my imagination and made every step possible. Those that kept their hold on me pleasantly occupied my thoughts for months if not years and carried me through whatever work I had to do to bring that daydream to life, even if it meant devoting the best part of a year to building a boat, carving oars, and sewing sails.

It’s not likely that I will take any cruises as long as those I did in my late 20s and early 30s, but even the least ambitious of my boating endeavors now begin with daydreams that knit ordinary days and weeks together with a sense of purpose.

It was late in the afternoon of the last day of October last year when it first occurred to me, here on a backwater of Lake Washington, that my recently acquired Piccolo canoe could be a very pleasant place to nap or even sleep on an overnight cruise.

Six months ago, when I first took out the Piccolo canoe I’d been given, I lay down in it for a few minutes before I landed and hauled out. It was very relaxing and, if I added floorboards to keep me out of the bilge water fed by my feet and paddle, I could sleep in the canoe perhaps even on an overnighter.

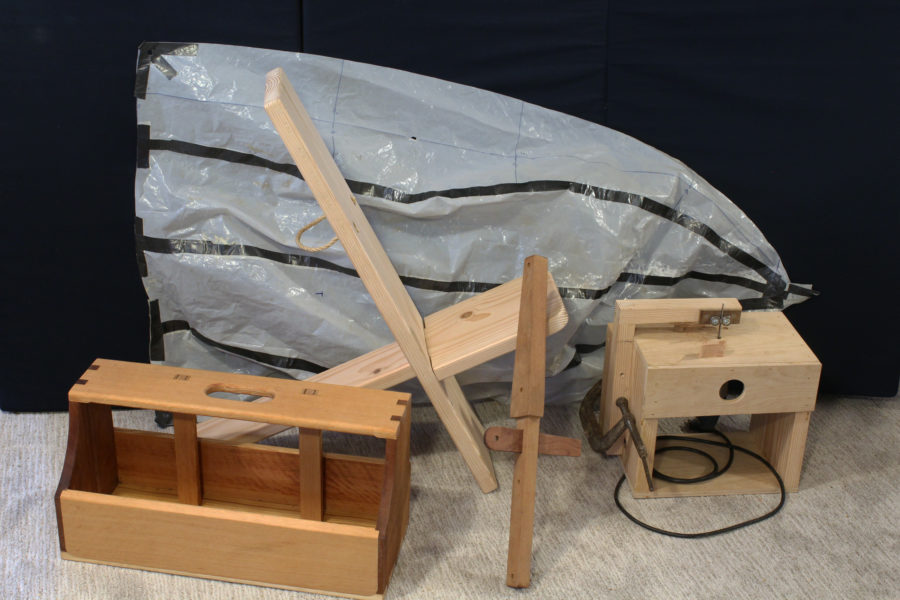

I brought the canoe into the basement and spent the winter working on it, installing floor timbers, refinishing the hull inside and out, and making a pair of floorboards. The canoe stayed in the basement while I made a cart for it and fussed with an arrangement for a canopy. During that time, I often set a camping pad in the hull, lay down on it, and pulled a sleeping bag over myself. It made a very comfortable nest, and I imagined falling asleep as a light rain fell on the vault of forest-green nylon stretched over me.

To photograph the canoe’s relaunching and my first onboard nap with my GoPro camera, I would need a floating monopod. On my second cruise up the Inside Passage I used my faering’s mast, rudder, and anchor chain to cobble one together to float like a spar buoy and support my 35mm SLR. For the GoPro, I made a much smaller one of plastic pipe, lead shot, and a piece of pool noodle to float vertically, in spar-buoy fashion, and support the camera in the middle of the pond I’d chosen for the outing.

I picked a drizzly Wednesday afternoon to take the canoe to Twin Ponds. I parked a few yards from the head of the trail that leads to the south pond. I was on the street side of my car casting off the rope that I’d used to tie the canoe to the roof rack when a panel van approached. I stepped quickly around the back of my SUV to get out of the way, but I failed to duck under the stern of the upturned canoe. I hit the left side of my head just above my ear. If it had been somewhere along the length of the outwale, it wouldn’t have been so bad, but I was hit by the rounded corner at its end, which had the shape and effect of a ball-peen hammer. Bent double by the blow, I stepped to the grass strip paralleling the sidewalk and, with my elbows on my knees, pressed my palms to the sides of my head until I could unclench my eyelids.

There is a place to park closer to the Twin Ponds, but I much prefer walking this winding path through the woods.

The cart rolled smoothly along the eighth-mile gravel walkway to the edge of the pond, but I had to haul the gear in several trips along the narrow, windfall-strewn path to the south end of the pond where I would put in. I finished the carry by hoisting the canoe overhead and picking my way through the maze of pewter-gray pine-tree trunks. With my last step to the bank at the water’s edge, I tripped on a root and twisted my left knee, the fragile one with the torn and surgically excised meniscus.

The pond was as tranquil as I had hoped it would be. There were even occasional sprinkles of light rain, just the thing to doze off to once I tucked myself under my tarp.

After I got the canoe afloat, I loaded everything in its ends and got aboard. I tried to push off, but it wouldn’t budge—it was high-centered on a root that had been invisible on the dark-silt-covered bottom and hemmed in by a fallen tree at the bow and the overhanging bank at the stern. I had to get out and stand in the muddy shallow to swing the bow away from shore and step back aboard over the backrest. As I did, water, pouring from my neoprene bootie, pooled in the hollow of the seat.

Underway finally, I paddled around the pond for a few minutes before setting up the GoPro on its floating monopod. I had thought that the bolt I’d threaded into the cap would be okay without a locknut to hold it there, but it wasn’t, and the camera flopped around like an inflatable tube man at a Jiffy Lube. I’d planned on operating my GoPro from my phone, but I spent 20 minutes without making the necessary connection, stuck on endless command loops on Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. (I found out later that day that my old GoPro 3 is no longer supported by the app.) I gave up after I drifted into the water irises on the north side of the pond and set the camera to take a photo every 5 seconds while I paddled back and forth in front of it hoping I’d get some useful frames.

I was worn out by the time I got to setting the canoe up for a nap and rolling the pad out under myself exhausted me further. Imagine making your bed while you’re on it…you can only lie on your back or sit up. During one of my contortions to get the pad under me, I pressed my left elbow against the upright that holds the seat back in position and there was a loud crack on the port side. I’d pried the gunwale apart, splitting five of its spacers as easily as if I’d jimmied the inwale and outwale with a crowbar.

This was as close as I got to the vision I’d had for the canoe. It was far from restful.

The outing was off to a bad start, but I was determined to get the photo of “napping” in the canoe. I pulled the tarp over myself and held the GoPro up high with the monopod.

I paddled back to the south end of the pond, dragged the canoe out of the water, and carried everything to the unobstructed part of the trail. With the cart reassembled and the canoe strapped on it, I loaded up and limped back to the car.

That day certainly didn’t bring the daydream to life. I wound up with a knot on my head, an aching knee, and a busted gunwale. But even if I ultimately have to abandon the idea of spending an afternoon napping or a night sleeping aboard the canoe, the five months that I have been happily occupied with the vision were their own reward; the success of each of those days well spent won’t be diminished by an afternoon gone wrong.![]()

“But, Mousie, thou art no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain;

The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

Robert Burns, “To a Mouse”

First thought: rigging, launching, rowing, and sailing a small boat seems to have endless opportunities for head injuries. I came within a whisker of buying a climbing helmet a few weeks ago. Perhaps these might warrant consideration for a review article?

Second: as a very green boat-owner, I had a friend help me get my Catalina 21 off its mooring and onto the trailer. My friend showed up in his 40’s era Internal Harvester pickup truck, not his Toyota Highlander. It was a calamity-filled day that included (but was in no way limited to) a parking brake failure on the ramp, a dead battery on the ramp, a cracked cabin top when lowering the mast, and ultimately a rear wheel flying off the when the axle broke.

When I saw him the next day I commented that it was quite an experience. He replied, unruffled, “Naw, just a typical day boating.”

And yet, we keep coming back.

Ahh, the real world… easy does it old man.

Pretty soon Washington will have us in HELMET IN THE SHOWER. I have paddled Interior Alaska in the bush for years and seldom came across people. Common Sense will beat a helmet any day.

Reminds me of the time….. Oh, so many times.

Yet we go back out.