For many, 2020 has been a rough year. I’ve been very lucky, in that my main hardship was being largely confined to quarters through half the year, first by an invisible virus, then by a blinding pall of wildfire smoke that enveloped Seattle. I missed my chance to get out for a summer cruise, but I was able to make a brief restorative escape with my smallest boat.

My coracle, FAERIE, is just 54″ long and built to be a folding tender for HESPERIA, one of my camp-cruising boats. She was never meant to go far, just from HESPERIA at anchor to shore and back. She’s neither fast nor seaworthy, so to take her on a cruise of her own, I needed to find a placid body of water scaled to her diminutive dimensions. Through satellite images, I searched the area north of Seattle, and I knew all of the small lakes I found—none of them held much interest for me except for a pair of ponds I had never seen before even though the park they were in was less than five miles from my home. I had passed the park’s west side by bicycle and by car countless times and years ago watched my daughter play soccer on its east side. The ponds were so well hidden by the woods that I had never caught a glimpse of them.

On a cool, overcast Tuesday morning, I packed a lunch, put FAERIE in the back of the truck, and headed for the park.

The path that leads to the Twin Ponds begins in that dark gap in the woods between the fire hydrant and the tree trunk just to the left of my truck’s cab. The only signs marking the park are set well back from the sidewalk and dimmed by the shadow of a dying willow; the road here is a 35-mph arterial, so it’s easy to race by without even catching a glimpse of them. Assembled, FAERIE fits neatly in the truck bed. The folding frame of laminated spruce is varnished, but I’ve kept the Port Orford cedar thwart unfinished. Even though it has been eight years since I built the coracle, when the sun warms the thwart, it is still redolent with Port Orford’s lemony fragrance.

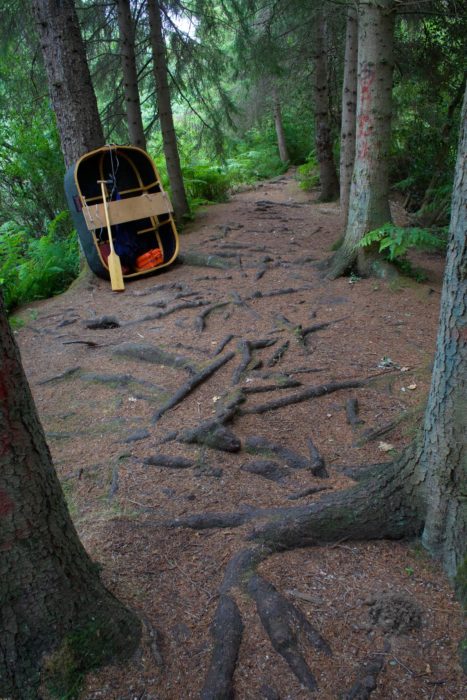

Coracles have always been meant to be carried. Mine weighs 27 lbs and I carry it as coracles have been carried in Ireland and Britain for centuries. With the seat set against my back, the rope hanging from it crosses my chest just below my shoulders and holds the coracle in place, leaving my hands free. The paddle, a dry bag holding my lunch, and my camera case hang from the painter behind the thwart.

The path swerves through the woods in gentle curves, so while its entrance and its end at the ponds are separated only by an eighth of a mile, the view ahead and behind is veiled by trees and brush in subtle variations of green. The sound of cars rushing past the trailhead was muffled into silence by the leaves until the crisp grating of gravel underfoot was the only sound. I knew from the satellite photos that residential streets run parallel to the path and there are houses only 50 yards away on either side of it, but they were hidden by a thick wall of cedars and salmonberry and as easily forgotten as if they had been miles away.

The trail led to the east side of the south pond at one of the few breaks in the brush at the water’s edge. Dead tree branches in the water with sharp broken ends kept me from trying to launch here. I continued my portage north and took the path along the 10’-wide strip of high ground that separates the ponds. I emerged from the woods and walked along the edge of the soccer field where my daughter had played some 15 years ago, then back into the woods on the east side of the north pond.

Thornton Creek trickles into the north pond after traveling from its source at Ronald Bog, a mile to the north, flowing through underground pipes for almost half of that distance. The creek approached the pond silently—its water so thin that it took the contours of the pebbles beneath it—and made its last bend around a Medusean tangle of soil-bare roots fanned out from a quadruple-trunked maple. I set FAERIE at the water’s edge and pulled her across the shallow of pale grey sand at the creek’s mouth.

I set out on my circumnavigation of the north pond on shallow water, careful to keep the tip of the paddle from fouling in the long strands of weeds on the bottom. The stroke I use is one I learned watching short movies filmed in Wales and Ireland in the 1930s. Instead of figure-eight sculling with the blade continually in the water, I slip the edge of the blade in from one side, pull it straight back, and then slip it out to the same side. With the blade slightly angled to create lift, the stroke provides propulsion through all three phases.

The shore of the north pond was crowded with lush plants either rising up from the still water or growing down into it. This web of pale-green willows dip into reflections made painterly by FAERIE’s wake.

At the south end of the north pond, I found the footbridge I’d crossed on my portage between the ponds. From the water side, its side fences were obscured by brush and the passage under it was blocked by a tangle of slender interlocked branches. To get to the south pond I’d have to portage.

There was no other break on the north pond’s perimeter, so I paddled FAERIE ashore on the same spot where I’d launched her. I made the portage around the north pond, completed a loop on foot, and continued on the path around the south pond. It was narrower and not so easily walked. Tree trunks were closer together and branches were lower; carrying the coracle, I took up almost as much room as a sheet of plywood and had to slip sideways and duck down to get through.

I found just one spot on the south pond where I could launch FAERIE. In between bracken ferns there was a 2′ drop-off where I could step into the water and lift FAERIE down after me.

Although the south pond is separated from its twin by a brushy berm no wider than a parking space, it had an entirely different character. The plants along the water’s edge were not growing in and out of one another, elbowing for space, as they were on the north pond, but distinct from one another, as if planted and tended to by a gardener. Cottonwood trees towered over the pond to the east and west, and its south end was spanned by a palisade of hemlocks with scaly grey-brown bark dusted with powdery green moss.

On the north side, long slender leaves of water iris rose in unfinished parabolic arches from patches of duckweed.

FAERIE, with her blunt square bow, can’t keep ahead of her own wake, and the silky corrugated ripples ahead of her turned the reflections of branches hanging over the water into patterns like those of combed marbled paper.

Blackberry brambles were in bloom and their berries were small and green, weeks away from turning crimson, a month from black. I doubt anyone has ever picked the berries here. By September they would have lost their firmness and their flavor and begin falling into the pond.

After I completed my loop of the south pond, I lifted the coracle to the clearing at the water’s edge and took a break for lunch. I’d only seen one person that morning, a woman jogging the path at the western entrance to the park, and my lunch was uninterrupted. Where I’m sitting in this photo is only 250 yards from the nine lanes of Interstate 5, the West Coast’s main thoroughfare. The noise of cars and trucks was so sifted by the woods around the ponds that I could easily imagine it as being the susurrus of a breeze shaking the leaves of the alders, cottonwoods, and willows. To my left, across the root-laced path, is a swamp that must have been the twins’ sibling until the press of plants surrounding tightened their perimeter and closed over it.

After lunch I packed up, strapped FAERIE to my back and threaded my way through the woods to my truck.

FAERIE and I didn’t travel far that morning, only a third of a mile on the water, and just shy of a mile if you add the portages, but, in a time when it is hard to escape the worrying news and devastating consequences of a world upended, it was far enough.![]()

A most interesting article — much enjoyed!

A thoughtful, beautifully written ode to the explorer in us. As terrible as this pandemic is, it has forced us to find pleasure and meaning in tiny expeditions aboard small craft. Thanks for giving voice to this.

Great micro adventure. Can you make one of your short videos on the paddle stroke you use?

You can find more information about FEARIE and the coracle stroke in my article, A San Juan Islands Solo. Scroll down to the last section. It includes a video I took of myself paddling FEARIE and links to the 1930s films I found that showed the strokes: Boyne Coracle, A Bygone Craft, and Peeps though a Window of the World.

How often do we overlook the beauty at hand in favor of the siren calling of a distant shore?