Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyHarry Bryan’s 12’ Thistle is powered by a large rudder shaped like a fish’s tail and driven by foot pedals. With steady pedaling you can keep pace with about any rowboat of the same length.

At the beginning of a family cruise to Tasmania some 25 years ago, our friend and frequent Wooden Boat contributor Harry Bryan became intrigued with pedaling a small boat with one’s feet as an alternative to rowing or paddling, leg strength being greater than that of the arms and hands. While at sea, and after having earlier tried out a little foot-powered paddle-wheel craft and finding it enjoyable but inefficient, he began studying how fish moved through the water with such speed and with seemingly so little effort. He caught and examined a number of fish, bending their tails back and forth so he could better understand how they worked. And, as is often his custom, Harry soon started planning how to build a practical version. Long periods of time while standing watch in the Pacific, it seems, got those creative juices really flowing.

Back home again in his New Brunswick shop after the voyage, the ideas for a fish-tail drive generated during those watches began to come to fruition. After building some full-sized prototypes and trying them out, Harry perfected his so-called fin drive.

In its first iteration, Harry tells me, it worked like a rudder in that its big blade, operated by foot pedals, simply swung back and forth. But as the concept evolved (and became more like a fish’s tail), a second pivot came into being partway back on the “rudder” that provided more articulation and increased the forward drive. This worked much better—well enough, in fact, for Harry to draw up detailed plans for sale. He also designed a boat specifically for the fin drive, the 12′ Thistle.

As you can see from the photos, the blade itself is made of thin Lexan sandwiched between a leading edge of the same (but thicker) material, both chosen for their ability to flex. In use, the fin hangs down about a foot below the surface to get a good bite on the water. But it can swing up if it needs to when striking bottom or to make the unit easier to deal with when removed from the boat. The fin assembly is demountable (a threaded hinge pin hangs it onto the transom bracket, and a couple of snaphooks connect the foot pedal ropes), but in use it extends well beyond the boat’s stern; it has to in order to perform so well. After all, it’s supposed to simulate a fish. It’s this streamlined piece of Lexan, bending as it swings back and forth, that pushes the boat ahead.

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyA spring and pin allow the fin to pivot forcefully through the water.

The mechanism between the fin and the boat that does the articulation rides clear of the water. This apparatus is very critical in that, besides supporting the forward tip of the Lexan fin, it has the pedal-driven yoke mounted at the front, along with the gudgeons and pin that make the connection to the boat’s transom. In between, there’s a second set of rudder-like hangers and a tiller (called a top piece on the drawing) that uses a tensioned coil spring instead of a human hand for its operation. By means of this device, the fin bends back and forth somewhat in concert with the forearm unit. In operation, the fin can really push on the water without stalling out, and shoots the boat ahead with remarkable speed.

It really works well, we’ve found, and leaves your hands free for holding a fishing pole, a camera or binoculars, or simply for waving as in, “Look, Ma, no hands.” You can alter course by pushing harder on one of the pedals than the other. Or you can simply stop pedaling and coast with the fin drive in the hard-over position, wherein the fin acts like a simple rudder. Either way works okay for a gradual turn, but for the tightest possible turning circle (and it’s still a pretty big one compared to most oar or paddle-driven boats), you keep the boat’s waggling “tail” toward one side and use rapid short strokes to kind of push the stern around.

Sculling by moving a boat’s rudder from side to side has always worked, but not efficiently. In a Beetle Cat, for example, this technique will get you home when the wind dies, provided home is not too far away. But with Harry’s fin drive, you can pedal for miles and go much, much faster without wearing yourself out. With steady and energetic pedaling, you can keep pace with about any rowboat of the same length.

The propulsion efficiency comes from the fin’s flexibility; it bends naturally as it swishes back and forth and pushes a lot of water aft, just the way a fish swims. With a combination of pivots, a yoke, and a centering spring, Harry has come as close to simulating a fish’s tail as you’re likely to see. While this device has a number of moving parts and may seem fragile, rest assured that Harry, his family, and others as well have proven it through many hours of use. I remember Harry’s daughter Sadie scooting around Mystic Seaport’s waterfront almost continuously during one of the three-day Wooden Boat Shows there.

The materials are commonplace, although there’s some machining and welding to contend with. There’s the Lexan fin itself (three layers, riveted together), some small pieces of plywood to contain it and make up the fin’s “tiller,” a bit of oak or locust for the yoke and forearm, and a few pieces of stainless steel to make the connections, pivots, and reinforcements. But all this is well detailed on the fin drive drawings.

Maynard Bray

Maynard BrayThree sheets of Lexan riveted together give the fin both strength and flexibility. The articulated plywood bracket pivots at the boat’s transom, while the fin pivots independently.

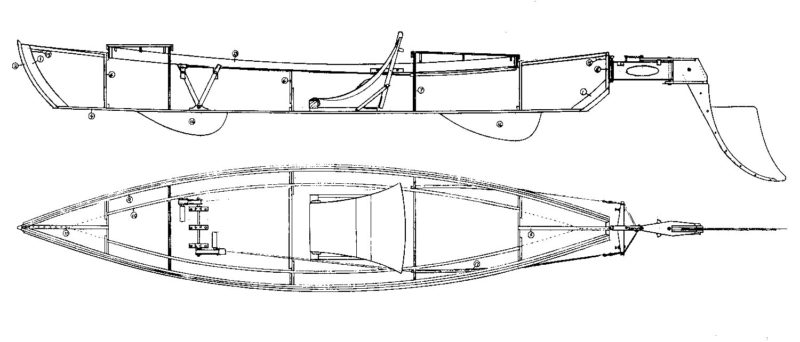

Now for the 12′ × 31″ boat that Harry designed especially for the fin drive and which he calls Thistle. The hull is built dory style with sawn frames, a flat bottom, and lapstrake sides. Like most of his boats, it’s designed for cedar planking, but one could adapt the design to lapstrake plywood construction. It weighs 65 lbs and carries only a single person within the cockpit. The bulkheaded stowage compartments in each end are accessed through deck hatches.

You sit facing forward in a comfortable canvas seat that is reminiscent of an early wood-framed lawn chair. The seatback can be adjusted fore-and-aft to fit various leg lengths and make the pedaling comfortable and effective. The pedals swing on a common rod held by three wooden cleats close to the boat’s bottom, and interact with each other by means of the 5⁄16″ braided ropes that run aft and connect each foot pedal through the yoke and finally to the oak forearm of the fin-drive unit.

To dampen the boat’s sideways wiggle as the fin swishes from side to side, Harry added a couple of permanent external keels to the boat’s bottom, one near the bow and the other aft. While these 6″-deep keels keep the boat from wiggling so that most of the energy you put into pedaling drives the boat forward, they are a bit of an impediment ashore. They’re thin and appear a little fragile, so you have to be careful to not damage them when launching off the shore or beaching.

As mentioned earlier, because of these two keels, maneuvering is trickier than in boats using oars or paddles. The turning circle is rather generous, and backing down isn’t an option. There’s no reverse. Either you coast to a stop, or you grab the single paddle that you hope is at hand, and bring the boat to a halt with it.

That said, the fin drive is a blast to use. The boat really moves fast; aiming it is intuitive; you’re comfortably seated in a canvas chair with your arms resting on the side deck; and you’re set for an all-day experience, if you choose. As Harry says on his website, “Although capable of keeping up with any oar or paddle propelled boat of her length, she is at her best silently swimming close to wildlife or just enjoying the waterborne equivalent of an afternoon walk.”

This same fin drive unit, I suppose, could work on other narrow lightweights as well, provided they have a strong flat vertical transom on which to mount it, and are fitted with keels or have some other means of dampening the side-to-side wiggle. My advice is to stick with the Thistle. It’s easy to build, looks good, and has proven to work. Granted, the fin drive is a bit of a gimmick, but a very enjoyable one that you can build yourself of readily available materials using Harry’s very detailed drawings. ![]()

Plans consisting of seven sheets and a 36-page instruction book can be purchased directly from Harry at Bryan Boatbuilding, 329 Mascarene Rd., Letete, NB, E5C 2P6, Canada; www.harrybryan.com.

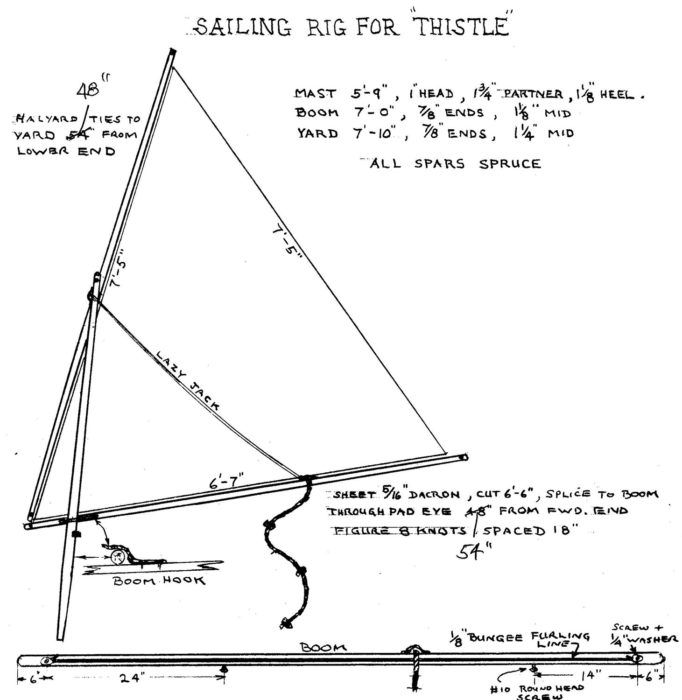

Harry Bryan

Harry BryanThe seven sheets of plans for the Thistle include extensive details on how to construct the fin assembly. Bryan also offers a sail plan—a nice feature for long distance runs.

Harry Bryan

Harry BryanParticulars:

LOA 12′

Beam 2’7″

Weight 65 lbs

Propulsion: pedal-powered fin or sail

Sail area: 22.5 sq ft

Just launched our Thistle last month (5/23) A fun build with lots of challenging parts. I opted for glued-lap construction and it works fine. I can’t quite keep up to a kayak but it takes little effort to keep it moving at a reasonable speed.

I bought the plans and I love the idea behind the fin drive. So please forgive me my following remarks. The boat could be nicely fit with a Mirage drive. There are two possible positions for that. Either, and most simple, in front of the seat, instead of the pedals, or behind the seat. In that case the pedals remain in place and connecting ropes go back to the mirage drive. Add a rudder and remove the fins. For sailing, attach leeboards.

I wonder what the relative efficiency would be. A drawback to the Mirage drive units on Hobie tris is that it is vulnerable to hitting the bottom, being located under the hull, and features more complex engineering.

I have converted two canoes with the classic Mirage Drive. The efficiency is excellent. The boat does not wiggle like the fin drive of the Thistle. If you ever hit the bottom, the draft of the short Mirage fins are roughly 12″, it stops the boat, thats it. No damage.

But there is a newer model with fins that swing up longitudinally, if one is concerned. I think use in coral waters might be the reason for that. The Mirage Drive unit itself is a well-thought-out piece of engineering, but installing it on a boat is not complex at all. (I am not paid by Hobie Kayak, nor am I an agent. I am a strict amateur and I love that drive.)

If I were to build a Thistle, I would probably substitute the fragile-seeming keels for a pair of short daggerboards. They would make for better handling ashore and in the shallows.

As for the fin drive, I bet an old scuba diver’s fin would work well too and simplify construction and use over the twin articulated joints and the Lexan. Of course, as Axel pointed out, the Mirage drive makes for a better, if more expensive alternative.