Shetland boats caught my fancy a long while ago, and Ian Oughtred’s careful interpretations of them retain their heart-catching beauty of line and also their incredible ability in turbulent water.

I remember trying to photograph boats at the delightful Scottish Traditional Boat Festival at Portsoy on Scotland’s Moray Firth, when a short steep sea had built up with wind against a four-knot tide. Every small boat there, every skipper, was frustrated, stopped in their tracks, sails and spars lurching—except for one. Iain Oughtred appeared in his lovely Ness Yawl, JEANNIE II, and slithered over the tops of the waves as if on some sort of buoyant magic carpet. Iain left the other boats standing, sailed rings around them, came back to see what was holding them up, like an irritating youngster who has completely outpaced the oldies. She was the only boat that day that photographed well, with hull, rig, and sails doing her credit. If I needed to get back to harbor in a turbulent sea and didn’t want to spend all afternoon doing it, I would feel confident that a Ness Yawl would not disappoint me.

Photo by Kathy Mansfield

Photo by Kathy MansfieldIain Oughtred has made a practice of designing—and using—lightweight, glued-lap plywood rowing and sailing boats inspired by the Nordic tradition.

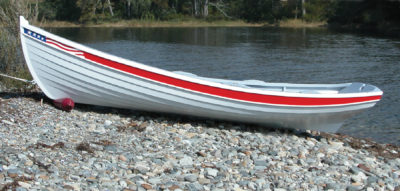

The historic type on which the design is based, the Shetland Ness Yole, was known to do the same, never happier than in a tide race where the sea was tricky but the fish were running. The shape is so buoyant at the ends, so built like a fish with her rounded bilge and clean double-ended lines, that she bounces over the waves and picks up less friction than a heavier, deeper, or less shapely boat. The Ness Yawl is a different boat, without the shallow long keel and the very low freeboard for rowing, but her hull shape still has similar characteristics. She may crash down on a wave, but she doesn’t dig in. And she’s fast. That was important to a Ness Yole fisherman: his boat needed to help him retreat to harbor quickly before an Atlantic gale hit, and even these traditionally built boats would surf well above their hull speed. The fishing grounds were mainly to the west, so the boats rowed upwind into the prevailing winds, and sailed back either with a load of fish—or with that ballast being shed before the greater urge for self-preservation. The Oughtred Ness Yawl is even lighter, and her 15′ 8″ waterline length gives her speed and also safety. Even as she comes up to a beach, her pointed stern will lift to and split the following waves, tracking well and in control. A good small boat can manage in ideal conditions: it’s her ability in those other situations that can materialize despite the best planning that are the deciding factor in my choice of a boat.

Photo by Kathy Mansfield

Photo by Kathy MansfieldIan Oughtred’s own Ness Yawl, JEANNIE II, is rigged as a gunter sloop, one of several rig variations he has designed for the boat.

I can’t think of a better sail-and-oars boat. It’s the philosophy of the boat, the idea behind her. To go back again to her origins, no Shetlander back in the 19th century planned to sail her upwind with a square sail, and when a more weatherly rig came along, she still moved so fast with a pair or three of oars that precious time was saved. Her stern doesn’t take kindly to an outboard, and the extra weight would be wrongly placed. As with all boats, you work your sailing around the boat’s abilities. She’s a bit lean, you might think, for sailing, but in fact like all Shetland-style boats she stiffens up as she heels. The waterline beam is considerably less when upright than when heeling toward the gunwale. In steady winds she’ll quite safely sail heeled somewhat over, her crew central and sitting up to windward, though I prefer not much more than 30 degrees. Iain Oughtred sailed to windward in 18 to 20 knots of wind under full sail and found she did remarkably well on her ear, beating her main competitor at the finish line, and it saved him tying in reefs. Some of us might not be so keen, or so adept, but it’s good to know it’s possible.

It’s here that the mizzen could come in handy, which is one of Iain’s possible rigs, but she heaves-to nicely without the mizzen, and the extra sail area is so small, it doesn’t really have the drawing capacity. A sloop rig might be good, but it’s less amenable to carrying passengers with its boom and kicking strap (as a vang is called here) taking up valuable space. A yawl configuration could be nice, the jib and mizzen making a good combination in heavy winds, or a jib could be put up instead of the lug in worsening conditions. But the balance-lug rig that Iain suggests is such a satisfying sail, so user-friendly and simple, I’d be tempted to just stick with it. Even the owner of WAHOO, built with a standing lug and mizzen, concurs in that. The lug sail goes well to windward, pointing up about 45 degrees and much further in gusts, so there’s no real need for a jib. In almost no wind at all, the Ness Yawl is apt to drift downwind, making more leeway than headway. That’s not what she was designed for; why not get out the oars?

Photo by Kathy Mansfield

Photo by Kathy MansfieldThe yawl rig, with a balanced lug foresail, keeps things simple in the cockpit but, in this case, necessitates a bentwood tiller to clear the mizzenmast.

I can speak with some considerable experience of rowing Iain Oughtred’s Ness Yawls, sometimes under racing conditions, sometimes beating every other boat. This is more a feature of the Ness Yawl than my own prowess: she rows cleanly and quickly, tracking well. Just look at the boat shape: she’s lean and long, shallow draft with low freeboard, easy lines giving no turbulence. It’s good exercise and good fun, much greener than an exercise machine, and adds variety to a day out on the water. Not many dinghies will row this well, and it’s an added pleasure to owning a Ness Yawl.

Photo by Kathy Mansfield

Photo by Kathy MansfieldFor the Ness Yawl he uses as a “Raid” boat and for light-air lakes, builder Wolfgang Friedl of Vienna, Austria, increased NO NAME 3’s sail area by adding a jib set on a short bowsprit.

Few boats developed from a traditional working boat are as adaptable to small boat sailing as a Ness Yawl, and few are as much fun. It’s worth remembering, however, that it can be adapted to different requirements. The ALBANACH is a Ness Yawl that has been half-decked with built-in buoyancy fore and aft and movable lead ballast. She’s steady in most winds, and can be sailed that much more as a consequence. The ballast is removable for rowing or for light-wind sailing. Again she’s a beautiful boat, and that again is a joy of the Oughtred designs. They sail really well, but the delights of ownership are many and varied. It’s no surprise that the designs sell so well.

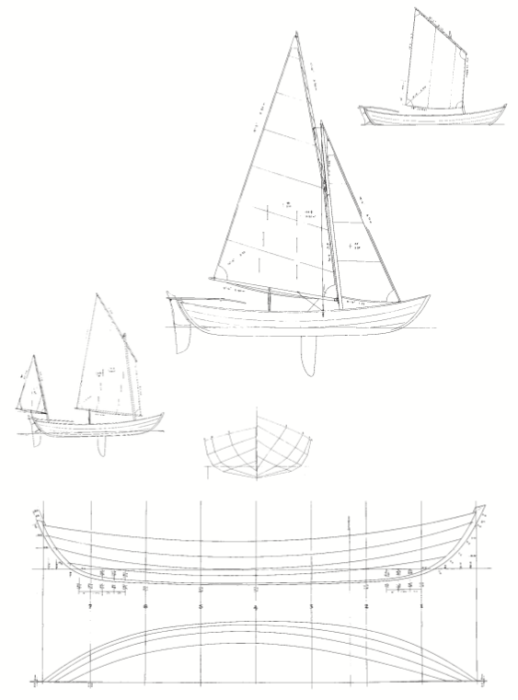

Iain Oughtred’s plans for the Ness Yawl are intricately detailed and thoughtful, and he offers enough variations on the sail plan to keep any builder thinking.

Plans for the Ness Yawl are available from Oughtred Boats.

This is one I’ve been thinking about, but I would be very tempted to put an outboard well in to use an electric trolling motor when I’m not feeling up to rowing. My sailing abilities put me firmly in the “less adept” category.

Jeff

You couldn’t find a better boat. I completed my Ness Yawl, WEE BIRLINN, ten years ago and have had so many great adventures aboard. I, too, thought about the outboard well but am glad I didn’t fit it, she rows so well but you hardly ever need to motor. Kathy Mansfield’s comment about drifting downwind in almost no wind and loosing steerage way is the only comment of hers that I would argue with. I have rarely found this a problem, in fact in such really light conditions I can sail rings around boats like the Bayraider 20s.

Given your “less adept” comment, one thing I would recommend is my compromise of using a 32kg (70lb) 1/2″ galvanized mild-steel centerboard (with ply cheeks to take up the full width of the standard centerboard case). We sail in all conditions here on the Western Australian coast, and after my first few sails getting to know her capabilities I would trust the Ness Yawl at sea over and above almost any other small boat.

Check out The Old Gaffers Association of Western Australia to see us in action.

Happy to talk to you more if you do go ahead to build the best ever little ship.

Jim

I would like to row solo … is this do-able with this boat? The lines MAKE this vessel!

A bit late to be making a Comment on this one, but one glaring mistake should be corrected. Kathy’s story is very good; she obviously appreciates the Ness Yawl, having sailed my first one, and another in the first Great Glen Raid. However, her excellent photos show a different design! – this is the prototype of the Arctic Tern, which is 18′-2″ OA, and a beam of 5′-1″ instead of the final design at 5′-4″. I wanted a slightly smaller boat, with 6 strakes a side instead of 4, for a maybe more traditional look. (Now there is also a stretched version at 19′-8″). And a more complex sloop rig, to see how it would compare with the balanced lug.

There was a slightly awkward statement about the centerboard; an early editor revised it, and somehow decided that the boat did not sail well close-hauled in a very light breeze. Suggested it’s time to get out the oars. Wrong. Both designs sail remarkably well in barely perceptible breezes.

Hi Iain,

Of your designs what do you consider the best balanced sail/oar boat for camp cruising for one or two people for a few days?

What are the Ness Yawl’s dimensions?