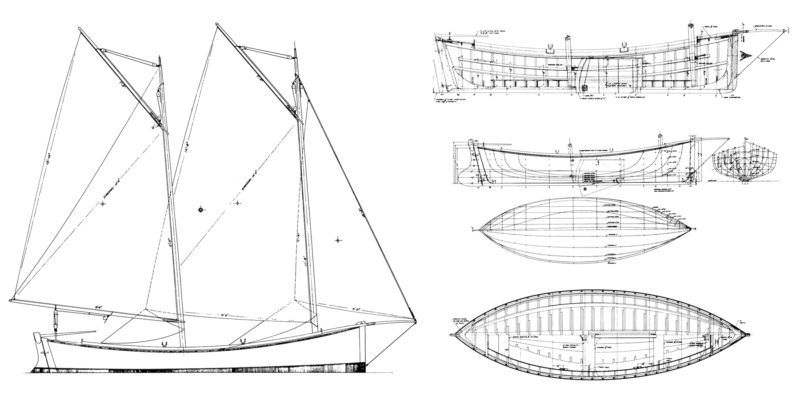

This boat is a pint-sized version of a well-known and respected type that worked Lake Michigan from the late 19th century until the beginning of World War I. It’s called a Mackinaw boat—though historically that name applied to a range of boats that have only tenuous family connections.

The plans for this 18-footer, designed by Nelson Zimmer, appeared in WoodenBoat magazine in July 1978. The first example was built as an exhibition in the lobby of a bank. Subsequent accounts of that project suggest that it remained on display there, never to be launched.

The WoodenBoat design review stated that “The spars and gear are simple, inexpensive, and not particularly finicky. An unusual detail is the main and mizzen halyards’ arrangement, combining peak and throat into one line for each sail.” A single halyard for a gaff-rigged boat cuts the volume of spaghetti in half.

Photo by Matthew P. Murphy

Photo by Matthew P. MurphyA Mackinaw in Maine. The 18’ Nelson Zimmer–designed Mackinaw boat, with her ample sail plan, takes full advantage of a dying southwesterly. Although the plans specify a single halyard for each gaff sail, the boat shown here has both throat and peak halyards.

The boat we sailed for this review was launched by Doug Hylan, a designer-builder and frequent WoodenBoat contributor, in 1982. (In a way, the boat launched his career.) Hylan did not use the single halyard specified, instead opting for separate throat and peak halyards. Twenty-five years later, he says he’d revert to Zimmer’s rigging plan, jokingly calling the boat the “world champion for number of feet of line per foot of boat.” There are other complications, too, though they are easily remedied. “I think the rig made sense,” said Hylan, “when the boats were 26′ long.”

Why?

“Because they had half the complications per pound of displacement.”

Hylan’s boat is now in the fleet at WoodenBoat School. I’ve long been fascinated with the type, and finally sailed WoodenBoat’s in August, trading the helm back and forth with my colleague Aaron Porter, an editor with Professional BoatBuilder magazine and a veteran schoonerman. The boat went like a freight train in a 7–10-knot breeze. She was also a handful, which I’ll describe in the form of a short digression into nomenclature and sheet leads. First, this boat is a ketch, though it looks like a schooner. The masts are of equal height, but there’s a few square feet of difference between the mainsail and the mizzen. The mizzen is set on a boom, and its sheet leads to the helmsman’s hand—sort of like a mainsheet would, except it’s a mizzen sheet. There is no cleat for it, though there’s archaeological evidence of one, in the form of four screw holes in the sole. Hylan’s boat sat for several years before coming to WoodenBoat, and the fate of the cleat (a swivel-based cam cleat, Hylan said) is lost in the mists of time. Its presence seems to be a linchpin to good solo sailing: you need a place to belay the mizzen while tacking the boat.

Back to nomenclature: The mainsail, then, is the forward gaff-rigged sail, and it is boomless. It has two sheets, as would a jib, and these lead to jam cleats near the helmsman, and are meant to be controlled by the crew. The reach to them is awkward for a solo sailor. A turning block and an ergonomic lead across the boat—and a means of easily belaying (and casting off)—would ease the job of tacking.

The jibsheets lead to jam cleats on the side decks, and need no further comment—except to say that the reach to them would be awkward, but manageable, for a solo sailor. This boat is set up for two or more.

I’ve gone on a bit about the shortcomings of the running rigging of our example boat. None of this is meant as a criticism of Hylan, whose catalog of designs and list of new builds and restorations speaks for itself. This boat sat for several years after Hylan had been using her regularly (and singlehanding with ease, he recalls), and a critical cleat has gone missing. As a school boat, she usually has ample crew, and so-staffed, the sheet leads as-rigged are not an issue. But for the solo sailor, they matter. I’m glad in a way that I experienced her like this; the absence of these things clearly defined the need. Once tacked and settled down, the Mackinaw sailed beautifully. Did I mention that she goes like a freight train?

Photo by Matthew P. Murphy

Photo by Matthew P. MurphyThe Mackinaw has a boatload of sheets to tend. But, rigged efficiently, the design can be singlehanded. Note that the mizzen halyards are belayed on the mast. If they led to the thwart instead, they’d add some security to the rig.

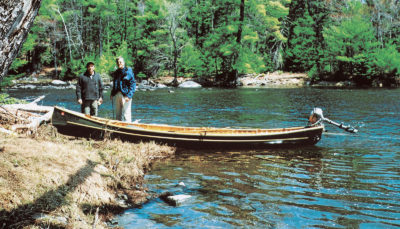

This paragraph from the old WoodenBoat review sums up the 18′ Mackinaw boat’s niche: “Anyone looking for a roomy, shoal-draft boat which would give a good account of herself in a broad range of wind and sea conditions, and with a variety of loads, would do well to consider this boat. She would be great fun for several people to sail or row, and she could also be a good friend to one seeking solitude. With her shoal draft she could sneak into some pretty tight places, or ground out at her mooring at low water without trouble. She wouldn’t be too big to haul up the beach when winter comes, either.”

Doug Hylan, however, questions the boat’s utility as a camp-cruiser. “She’s too heavy,” he said. “You get tide-nipped, you’re there.” He’s right about that, of course. There are many boats on the market that have this kind of volume—or even more—and yet are lighter. A sailor shouldn’t be completely swayed against camping in this boat, however. A properly rigged outhaul anchor will get it to deep water for the night.

Twenty-five years of hindsight have helped Hylan form another opinion about the boat: He thinks it should be a sloop, rather than a ketch. He’s had more experience with the boat than most people around here—indeed, he nearly dumped her in a sudden squall. I must say, however, that I’m rather taken with the rig (sheet leads aside) as configured—and not just because it looks right. The colossal sail plan would be a delight (is a delight) in evening zephyrs, and shortening options are numerous. Here they are, gathered during a conversation with builder Hylan: For the first reef, you reduce the mizzen. For the second reef, you douse the mizzen entirely, and proceed under full main and jib. For the third reef, you douse the jib, sailing under mainsail alone. A quick study of the sail plan suggests that the boat will remain balanced. Finally, you can reduce and then dump the mainsail, proceeding under bare poles.

Those masts, by the way, are unstayed, and this simplicity of standing rigging provides a great counterbalance to the relative complexity of the running rigging. But, sailor beware: WoodenBoat’s waterfront director reports that the mizzen has jumped its step in the past, on the mooring in a lumpy blow. The remedy for this behavior is simple: cleat the halyard on the partners (the after thwart) rather than on the mast, as it’s done now. The tension of the halyard will keep the mast put.

Photo by Matthew P. Murphy

Photo by Matthew P. MurphyThis 18’ Mackinaw will sail in a range of conditions, though the first reef must be taken early. The reef nettles seen flying here are on the mainsail; they’re the last of four options, before dousing everything and proceeding under bare poles.

Here’s another quote from the 1978 design review, addressing the matter of construction: “She would be a moderately easy boat for the experienced amateur to build, with no particularly complex structures to deal with, and no need to be very concerned about saving weight.”

Which brings us to ballast. My colleague, after being surprised at the boat’s short “carry” when shooting the mooring on his first attempt, reckoned our example could use several hundred pounds more ballast. Hylan concurs; years ago, when he still owned the boat, he removed a portion of her inside ballast and melted it into a shoe that he bolted to the keel, freeing room inside for more lead pigs.

Doug Hylan reckons the boat would take a professional builder 1,200 to 1,500 hours, and thus cost about $40,000 to $50,000 to have one built. As great as this design is, that price has some stiff competition in the marketplace. A professional builder is not likely to make a career building Mackinaw boats. But this should be an inspiration, and not a deterrent, to would-be amateur builders. This figure supports John Gardner’s notion that the survival of traditional small craft like the Mackinaw boat rests in the hands of amateurs. (Gardner was a boatbuilder, a teacher, and the Curator of Small Craft at Mystic Seaport Museum. His writing and teaching inspired many builders to the profession—and many more amateurs to the avocation.) Boatbuilding is fun and rewarding, and to re-create a Mackinaw boat in one’s garage would be a wonderful way to spend 1,500 hours—far more wonderful than two or three years’ worth of sitcoms, in my opinion.

I’m reminded of a story I was told once of a woman who’d built a boat, and was asked how long the project took. The questioner expressed surprise at the hours, and at her dedication. Her simple retort: “It would have taken that long not to build it, too.”

With the after sail a few square feet smaller than the forward one, the Mackinaw is labeled a ketch. The plumb ends and deep forefoot are hallmarks of the type, as is the straight keel with no drag (or slope).

Plans for the Mackinaw are available from The WoodenBoat Store, P.O. Box 78, Brooklin, ME 04616; 800–273–7447.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

There’s another option for rigging this. Conor O’Brien had an 24′ boat he rigged as a Gunter Sprit.

The boat, as rigged with the many sheets, was a great teaching tool when I taught small boat sailing at WoodenBoat. Plenty for people to do. I recall a couple of turning blocks for the mainsail sheet that allowed the lead to go forward. And I recall it having ballast, but not sure if that was normal or not. Lots of sail moved it well in light air.

A good-sized boat for camp cruising on the Great Lakes. Weight not a problem with no tide, and lots of lines and complexity to play with while sailing.

As a sailmaker of small traditional sails, I am very interested in your comment that the peak and throat halyards were combined into one. Looking at the line drawing it shows that they are, as normal, two separate halyards. I realize that in Conner O’Brien’s book he suggested a single halyard system, but as such it was only a theoretical suggestion. If possible, please can you supply me with more information on this ‘single halyard system’?

Thanking you

Hi Richard,

Maybe your question has been answered, but in case not: it is actually one halyard if you zoom in on the drawing in the article. There is historic precedence for the single-halyard gaff rig. I remember reading about it in American Small Sailing Craft. It might have been in Mackinaw boats, but my recollection was that it was an East-Coast type. Anyway, in the drawing, the halyard starts at the becket of the peak block, thence around the upper mast block, back through the peak block, down along the top of the gaff, through the throat block, and up and through the lower mast block, and finally down the mast. Getting the proportions right are, I imagine, key to getting the right tension split between throat and peak. It struck me as such a clever arrangement years ago, and was surprised it wasn’t more common. I didn’t know it was in use in a “modern” design until finding this article just now! Hope that helps.

I have a 28′ Egret sharpie, cat ketch rigged, built by Geoff Kerr. This boat has the single halyard gaff on both main and mizzen. It is simple and easy to rig and sail single handed.

Dr Jones, may I ask you to explain how this vessel was reefed? When easing the halyard, doesn’t the peak tend to drop first?

Thank you

I own a Crotch Island Pinky designed and built by the late Peter Van Dine. I’ve often thought that a rig similar to this, possibly without the headsail, might be better looking than the spritsail sail plan it has now. The boat was also lauded in Howard Chapelle’s book. I’m not one for changing for changes sake but I’m not versed in the spritsail rig and would be interested in the single-halyard gaff as an alternative. It’s a very similar design but this seems a bit overpowered, in my opinion.

2 comments/questions:

–Why not reefed mizzen/jib for heavier winds? I sailed a ketch for many years, and jib-and-mizzen was a fantastic choice, with great balance and ease of handling without the main in the way.

–Doesn’t the boomless main’s sheeting angle change with point of sail, requiring a constant adjustment of the angle as the point of sail changes? Wouldn’t it be better (simpler!) to reduce the sail area of the “main”, add a boom, and make it an honest schooner?