Most “honest” sailors (is that an oxymoron?) will admit to having flirted with a one-design class. With the combined appeals of match and fleet racing, of innovation and “interpretation” of the rules, of cutting-edge technology and long-steeped traditions, one-design racing enriches sailing on a completely different plane than just pottering about the harbor in any old boat. That dream of building a one-design and then campaigning her is merely a rich fantasyland for most of us, and fulfilled for very few.

The boat presented here is intended to offer this possibility to the rest of us. She is a high-tech, cutting-edge, extreme racing machine with a serious nod to history and tradition, buildable by amateurs, affordable, and transportable, with the potential for class events and the promise of fun whether sailing alone or in the fleet.

This new 16/30 class sailing canoe is the product of a long-term project on the part of John Summers, General Manager at the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough, Ontario. He designed the canoe while at the Antique Boat Museum in Clayton, New York. The ABM has a long standing as a bastion of the mahogany speedboat crowd, but it deserves at least equal stature as both a repository and an enthusiastic reproducer of classic small craft. The fact that Clayton and the Thousand Islands region have long been the hotbed of sailing canoe development (see sidebar) led Summers to a natural interest in promoting the type. A survey of existing boats and enthusiasts exposed, however, a situation without much promise for growth: owners were reluctant to bash their lovingly restored antiques around the buoys, reproductions were challenging and therefore expensive to build, and the bloody things were difficult and uncomfortable to sail.

To have a chance of reinvigorating the class, the world needed a sailing canoe that was easily and inexpensively built, could be sailed by a wide range of sailors, and was a true one-design (i.e., the boats would be well matched). Not content with that set of apparently limiting parameters, let’s throw in the desire to have the design based on a boat from the glory days of the class, say a century or so ago.

Geoff Kerr

Geoff KerrNo racing boat is complete without a competitor, and several 16/30s were built in a workshop at the Antique Boat Museum.

Summers based the concept for the new 16/30 class on a boat built by the Gilbert Boat Company of Brockville, Ontario, one of a number built circa 1920 for the Gananoque Canoe Club from the Canadian side of the Thousand Islands. He found the archetype pre-served in the collection of Heritage Toronto and was able to visit and document the boat in 2004. Longtime sailing canoe builder, sailor, and pied piper Dan Sutherland took up the gauntlet at this point, and from John’s data built the prototype of the new class, STORMY SKY ES. Her debut at the ABM’s Antique Boat Show in 2006 proved her a great success, both as a sailboat and a prize-winning crowd pleaser. The next step was to make her duplication possible by the masses.

First, her lines were converted to “analog” plywood patterns for stitch-and-glue construction, STORMY SKY ES having been constructed in “traditional plywood” style with frames, chine logs, and sheer clamps. Then a week-long workshop was offered at ABM to produce several new hulls at once—an instant fleet, if you will. Chesapeake Light Craft digitized the panels and CNC-cut the needed batch of hull kits. Sails were designed and built by Douglas Fowler of Ithaca, New York, to complement the carbon-fiber masts developed for the boats by Tony DeLima of ForteRTS.

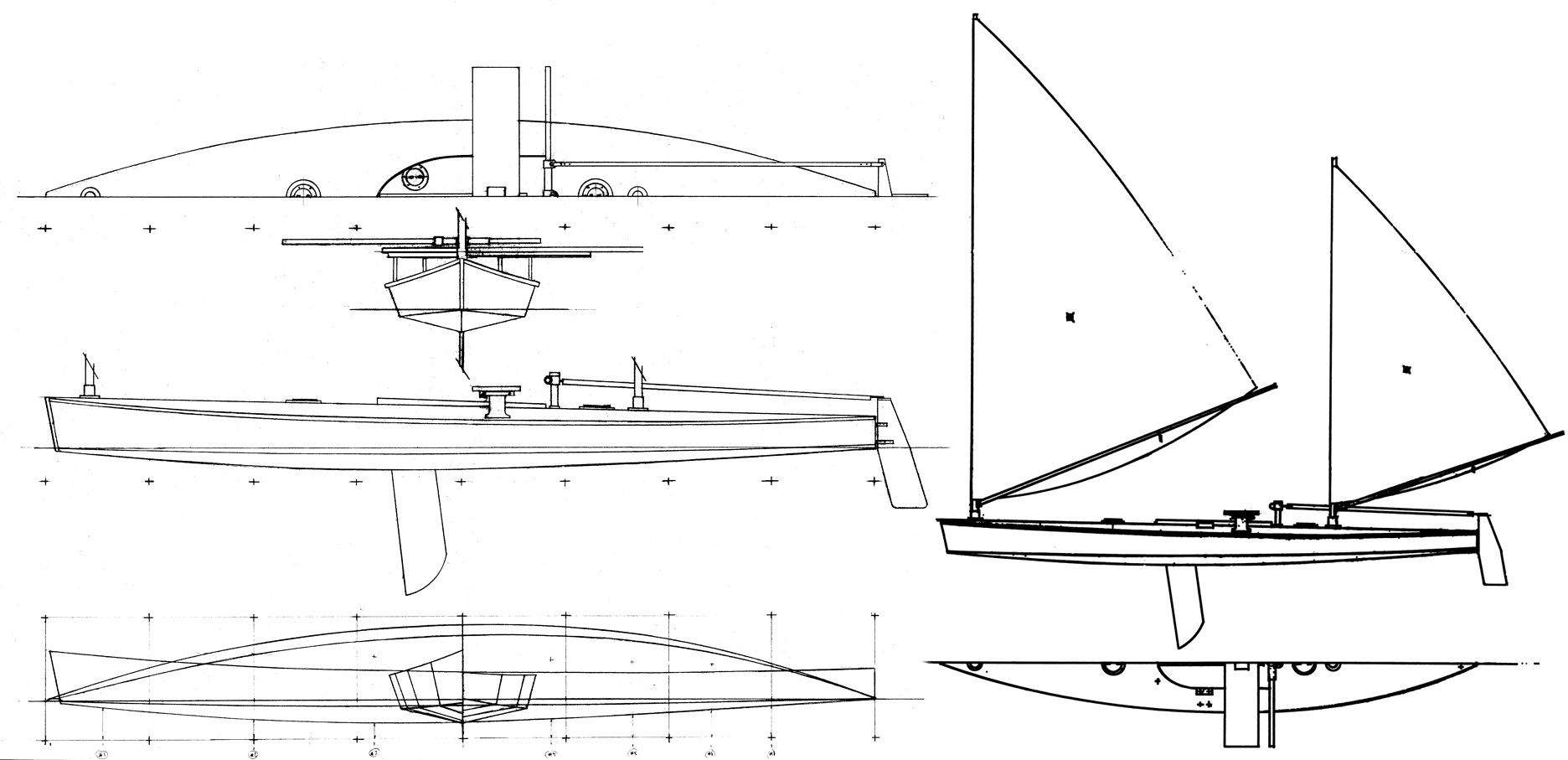

The resulting boats are reasonably true to the originals, and with a traditionally inspired finish job they could look at home on the Sugar Island float. The hulls are hard-chined and fully decked, with a small cockpit—really a footwell—that is self-draining through the daggerboard slot. The boat is steered by a Norwegian tiller rig, with a side arm on the rudderhead connected by a push/pull rod to an athwartships tiller. The hull construction is of 6mm and 3mm marine plywood, epoxy glued and sheathed in ’glass, with multiple bulkheads that stiffen the hull, support the decks, and create watertight compartments for positive buoyancy. Building the hull would be a similar-sized job to a large stitch-and-glue kayak, with the added challenge of complex but small-scale framing adventures in way of the cockpit.

The History of Sailing Canoes

Sailing canoes and cruising and racing in them date back to the mid-19th century. The first decked canoes built specifically for recreational sailing appeared in Great Britain in 1868, closely following the establishment of the Royal Canoe Club in 1866. Within a very few years, the boats had been discovered in the United States, with the New York Canoe Club being founded in 1871. By 1890, there were upwards of two dozen recognized canoe clubs on the U.S. East Coast. The American Canoe Association (ACA) was formed and held its first annual camping and sailing gathering in 1880. Sugar Island, near Clayton in the Thousand Islands, became the permanent home of the ACA gatherings in 1902. Such gatherings became boating and society happenings both in North America and in the U.K. International challenge racing was so competitive that new boats were designed and built every year, and those boats shipped hither and yon and across the pond. Paul Butler, an enthusiast from Lowell, Massachusetts, was the driving force behind many of the key features that made the boats popular, championing bulkheads for buoyancy, and by all accounts inventing or at least adapting the cross-sliding seat, Norwegian tiller steering, hollow spars, and the self-draining cockpit. By 1890, these improvements in survivability and manageability had led to such interest that the 16/30 racing class was established, with a complex rule resulting in a number of designs that were generally 16′ long by 30″ wide (hence the name), with a 90-sq-ft sail area.

The ultimate modern evolution of the sailing canoe is the IC class…recognizably a 16/30 on steroids. Come to think of it, design-enhancing substances must have been around back in the day as well. Check out WB No. 164 for an account of the “88” class of super canoes. –GK

Geoff Kerr

Geoff KerrJohn Summers designed the 16/30 canoe to be built with off-the-shelf hardware, requiring no complex casting or custom work to drive up the cost of construction.

The rig is really quite simple: there just appears to be a lot of it on such a small platform. She is set up as a cat-ketch. The unstayed masts are stepped through tubes built into the decks. As well as keeping the watertight compartments inviolate, these tubes make rigging the boat on the beach child’s play. Luff sleeves on the sails (the same system used in Lasers) both refine aero-dynamics and eliminate a bagful of hardware and line. Continuous sheets for both sails lead on deck to cam cleats at the cockpit, mounted just forward of the skipper both port and starboard, allowing instant one-handed sail control on both tacks. Off-the-shelf rudder hardware is used to hang the small but efficient wooden rudder, and the daggerboard, also of wood, is simplicity itself— jam it down into the slot, and off we go. The most significant characteristic of the 16/30s is the sliding hiking board, or “thwartships sliding seat” as it is called in period literature. In spite of its forbidding appearance, it is actually the civilizing feature of this design, making the boat comfortable (even for a large “mature” adult) and far less strenuous to sail than those rigged with knee and abdominal-trashing hiking straps.

This design and setup contribute to a logistically manageable boat. She can be transported on a very light trailer by a very light vehicle, or loaded on a cartop rack by a couple of reasonably able adults. Throw the spars up there too, and the rest of the gear is small, light, and easily packed away, leaving room in most vehicles (though regrettably not in the boat) for the cooler and companions. With one of those companions, or a “Tom Sawyer’s fence” onlooker, you can easily carry her to the beach for rigging and launching.

Our real quest is the sailing, though, so let’s have a look. The skipper stays on the hiking board, because: (a) there is no other place to go and (b) anywhere else would spell a swim. With one’s feet in the footwell on either side of the hiking board, everything you need is at hand: the mizzen and main sheets just forward, and the cross-arm tiller poised aft. The steering is very light, a combination of a nicely balanced rig, great leverage, and a small rudder. The unusual-looking steering system is really very simple and quite natural in use…just don’t look at it while underway! The sheet loads are minimal, a function of small sails and mechanical advantage, although the number of feet of line squirming around in the footwell is quite impressive and somehow tends to end up long on one tack and short on the other. That will make for an interesting jibe around the mark someday. The boat is responsive to sail and crew trim, to say the least, but well within the realm of small, light sailing craft. The 34″ beam and hard chines give her a greater initial stability than many (I’d bet all) of the other classic 16/30 designs.

Trimming the boat is easy and natural. The trick is to shift the board all the way to windward while tacking, then to slide yourself in and out as necessary while sailing. No great effort is required, you’ll suffer no grooves in you buns, and you will have time to concentrate on sail trim, steering, and tactics without desperately clinging to the boat. I’d call her far better mannered than the other sailing canoes I’ve endured, and in many ways more comfortable, better behaved, and far more intriguing than many of the modern one-design dinghies foisted on the competitive-minded sailing public. I like to think of 16/30 sailing as a dance rather than an athletic endeavor.

The most difficult and awkward moment in sailing this boat is the transition from beach to sailing…shall we call it the mount and dismount? The usual shallow-water daggerboard and rudder bugaboos apply (why does the wind always blow onto the beach?) and with a hull that is extremely sensitive to the first step, I’ll predict a few swims at bathtub depth. That said, my dignity and dry shirt survived a day of demo sails. Take a deep cleansing breath, tread lightly, and distract the audience.

Geoff Kerr

Geoff KerrThe sliding seat keeps the helmsman’s ballast weight where it needs to be, and allows rapid adjustment—while still keeping control of the sheets and the tiller.

A major part of the appeal of a 16/30 as a project is that Summers and the ABM have gone to great lengths to make it amateur-friendly. The large-size high-quality drawings are accompanied by an enthusiastic manual of more than 30 pages that includes historic photos; discussions of useful tools, books, and materials; step-by-step instructions with illustrations; and something very rare, a list of sources and part numbers for hardware, materials, and equipment. Much of the work of matching specifications and sourcing materials that could bog down a novice has been done, eliminating, for example, the sometimes fruitless (though sometimes really intriguing) pursuit of custom hardware. Knowing in advance that a call to ForteRTS for masts, to Douglas Fowler for sails, and even to Chesapeake Light Craft for precut plywood hull panels will put you days ahead of the game is a great comfort.

I’d now like to offer some minor caveats here. Some of the recommended sources and materials for the hull construction are not my favorites. No one is steering you wrong, but do not be afraid to ask and shop around. While you are building, I’d suggest ’glassing the deck as well as the hull, enhancing its stiffness, durability, and the life of the finish. When I build mine, I’ll stare long and hard at the transom, hoping for inspiration and new hardware so she could be truly double-ended. Finally, in converting to stitch-and-glue construction, I’m puzzled that inner and outer stems endured. Not only are these vestiges of traditional construction a challenge for novice builders, but a filleted and taped stem joint serves the stitch-and- glue world successfully in all scales.

A philosophical note is in order regarding one-designs and their convenient standardization. The 16/30 world welcomes one and all, for the more boats the merrier. That means there is room for individual expression in the building of these boats. The boats can be clunkers or professionally sculpted icons, and depending on craftsmanship and finish work they can look like modern rocket ships or century-old antiques. Wooden spars, polished bronze blocks, stained decks, and myriad other choices could make for a show-stopper. Just be a good sport and keep the hull shape and sails true to class, or the other kids might not let you play with them when you show up at the No-Octane Regatta, The Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival, or the ABM Antique Boat Show. See you there!

Simple construction using 6mm and 3mm okoume plywood and an uncomplicated rigging plan make the 16/30 canoe easily within range of an amateur builder. The thoroughly detailed instruction book will help in that regard, as well.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2009 and appears here as archival material. If you have more information about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Sail surface? Main y Mizzen?.

P.M.V.

Where can I get plans?

How can I order plans?

When the review was published in 2009, this was the information provided:

Plans for the 16/30 canoe can be ordered from the Antique

Boat Museum, 750 Mary St., Clayton, NY 13624; 315–686–4104;

http://www.abm.org

—Ed.