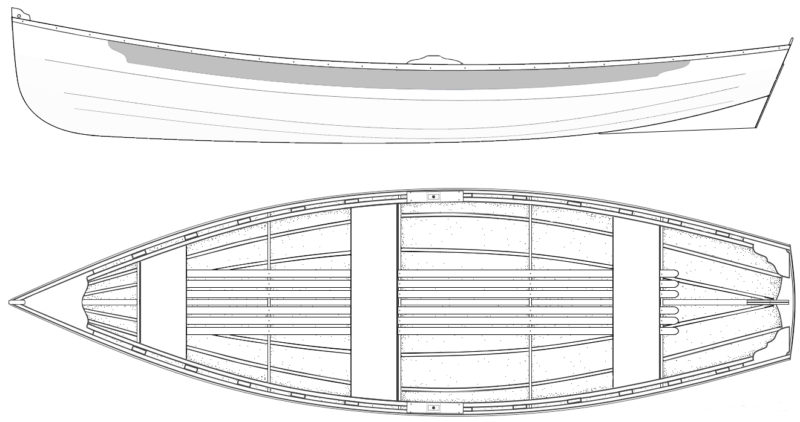

The description of the Shenandoah Whitehall was clearly too good to be true: a modern boat with traditional lines, large enough to take an adult and a kid camping, relatively seaworthy, efficient under oars, and light enough to toss on the roof of the car. According to the Gentry Custom Boats web site, the Whitehall could be built in a one-car garage workshop and, for a few hundred dollars and a few dozen hours, provide a novice with both a manageable entry into boatbuilding and a capable—even excellent—small boat for all sorts of flatwater adventures.

As a neophyte boat builder looking for a first project, I wanted all these things, but I couldn’t bring myself to believe that one boat could provide them. I reluctantly turned back to the haze of internet research. For the next year it was all reading, no building, but in the end, I came back around to the Shenandoah Whitehall.

Virginia Reinhart

Virginia ReinhartThe author could row the easily-driven hull at a 3-knot cruising pace and hit 4.8 knots in a short sprint.

Whitehalls have a storied lineage. In American Small Sailing Craft, Howard Chapelle describes the Whitehall as “perhaps the most noted of American rowing work-boats” and notes its “fine qualities…it rowed easily and moved fast in smooth or choppy water; it was safe, carried a heavy load easily, and was dry.”

Dave Gentry modeled his family-friendly Shenandoah Whitehall after a New York Whitehall in the Mystic Seaport collection. Its voluptuous hull suggests both capacity and ease in slipping through the water. I have spent enough years in performance racing shells to understand the limitations of a skinny sliding-seat boat; I knew I wanted more than just straight-line speed, and I liked the good seakeeping ability promised by its salty lines.

While the Shenandoah Whitehall’s shape is traditional, its skin-on-frame construction is not. Transverse frames of 1⁄2″ marine plywood support redwood or Western red cedar chines, gunwales, and keel. Builders may elect to glue and screw this frame together, or to lash each joint with polyester artificial sinew. Once complete, the frame receives a covering of fabric, heat-set to a tight fit then sealed with paint. The result is a 13′ 6″ boat that has a carrying capacity of 600 lbs and weighs under 60 lbs.

Virginia Reinhart

Virginia ReinhartThe author added a few features that increased the weight of his Whitehall, but at around 60 pounds, it was still light enough to carry and cartop by himself.

While Gentry offers kits for the Shenandoah, I opted to work from plans. They include templates and are available as digital downloads or, for a reasonable surcharge, in printed format. I was glad to have the printed copy. The detailed 22-page instruction booklet had a reassuring heft and would prove constantly useful, and the printed frame templates were easy to spray-glue directly to marine plywood stock for efficient and accurate shaping.

The construction went quickly. Every major project I’ve ever begun has a hidden “gumption trap”—a difficult and unrewarding challenge that sucks the will to persist right out of me. This skin-on-frame boat was an exception. Each evening or weekend hour brought visible progress. In the end, I finished the boat in about 75 hours over three months, while also working a full-time job, raising a toddler, and making a pair of oars. A more experienced builder could probably finish the boat in 40 hours.

From the start, the Whitehall provided an engaging and educational build. With the strongback built and the frames in place, the boat suddenly took shape. At this point, gawkers began to show up. I met four families who have lived in my neighborhood for years but who had never stopped by to chat until they spied the Whitehall up my driveway. There’s something about the shape of a pretty boat that compels people to interrupt your work with questions.

With the frames set up, the next step was to fasten the outwales to them. In the finished boat, the laminated outwale-spacer-inwale assemblies are the largest and most rigid longitudinal members, so their shape and strength will determine the sheer. Because the sheer has a pronounced curve in the vertical plane, Gentry calls for laminating the outwales from two pieces, stacked one on top of the other, in place on the frames. The goal is to avoid edge-setting a one-piece outwale, which would tend to spring back and flatten the sheer after the boat is removed from the strongback. Cleaning up the epoxy that squeezed out of this lamination was a bear, but I won’t argue with the results. To my eye, the sheer of the finished boat looks right.

The keel and each chine must attach firmly to each frame. For these joints the instructions offer two options: lashings or screws and glue. I’ll take lashing over epoxy work any day. I used artificial sinew passed through countersunk holes drilled in the frames. This was a satisfying technique. As I worked through the joints and felt the entire structure stiffen, any lingering concerns about the strength of lashing dissipated.

Gentry’s plans call for 1⁄2″ marine ply for the breasthook and knees, but encourage the use of lumber and more traditional methods. I cut my breasthook and knees from a walnut crotch that I’d been air-drying under the house. The same slab made a handsome skeg. These highly visible pieces are worthy of solid lumber, and only cost of a few additional hours of time.

Michael Reinhart

Michael ReinhartThe plans call for a simple transverse thwart in the stern. The author’s stern sheets provide a a more spacious seating area.

I milled floorboards to the specified 1⁄4″ × 2″ dimension from some salvaged tropical hardwood—possibly khaya). At each end of the boat, the floorboards rest atop the frames; in the central portion, the floorboards slide through slots cut in the center of the frames. Lowering the floor into these slots increases stability and locks each board in place. Another benefit of these slots later became apparent: when rowing in the central station, my feet naturally braced themselves against the protruding upper edge of a frame. The built-in stretcher makes the rowing all the more pleasing.

As designed, the Shenandoah Whitehall’s seating arrangements are three thwarts made of 1⁄4″ marine ply supported by cedar cleats and posts. I had some salvaged redwood and an interest in a more traditional appearance, so I opted to use solid lumber. I also chose to build stern sheets in lieu of the aft thwart. These changes make the boat slightly heavier, and yet they get a lot of compliments. Panels of 1″ closed-cell foam insulation, glued under the thwarts, provide flotation.

With the frame complete, it was time to skin. I had no experience with fabric, but following Gentry’s detailed and supportive plans was straightforward enough that I never worried. I skinned the boat with the specified 9-ounce polyester. Because the fabric is nearly entirely fastened to the frame before it is cut, this process would be pretty hard to get wrong. A hot knife (I used a flat tip on my soldering iron) makes quick work of trimming the fabric. After a few coats of paint and the attachment of the rubrails, the boat was ready for launching.

Michael Reinhart

Michael ReinhartThe instructions include the option to add a forward rowing station by putting oarlocks on the gunwales and acknowledging “the oarlocks will be closer together here but do not be put off by cross-handed rowing—it’s quite easy once one gets used to it.” Outriggers, like the experimental ones here, can increase the span between the locks to match the main rowing station.

The plans indicate two rowing stations: the central thwart for a solo rower, and the forward thwart for a rower carrying a passenger. With the oarlocks for the forward station fitted to the gunwales, the resulting narrow spacing of 30″—14″ less than the span at the solo rowing station—will create either an awkward overlap of the handles or a high gearing and difficult rowing. I prototyped some steel-and-plywood outriggers to increase the span at the forward oarlocks. They drop into the gunwale spaces and lock in place with a stainless-steel machine screw set into a threaded insert in the uppermost chine. These quick-and-dirty outriggers are too inelegant and flexible for a boat this pretty and I’ll rebuild them, but they do create a comfortable 44″ span and are much appreciated when rowing with passengers.

Carrying only a rower, this light boat comes up to speed in a few short pulls and happily gurgles along under gentle, slow strokes. With a passenger and cargo aboard, the boat is notably slower to accelerate, but hardly any more difficult to keep at speed.

I measured speeds under a variety of conditions both with and without passengers using a GPS app on my iPhone. At my comfortable, all-day pace moved the boat at a shade over 3 knots. An aerobic exertion—the kind that quickly works up a sweat—would sustain a 4-knot pace. An all-out short sprint hit speeds of 4.8 knots. (Not surprisingly, 4.8 knots is the exact theoretical hull speed of a hull with a 13′ waterline length.) The Whitehall is remarkably easy to move at a pace that will get you where you want to go.

The Shenandoah Whitehall handles less-than-glassy conditions with aplomb; both rower and passenger can count on staying dry. When solo, I feel entirely comfortable rowing into Force 4 winds on the lee shore of San Francisco Bay, dodging the wakes of ferry boats and tankers. In this chop, a passenger in the stern sheets would take an occasional splash. The boat’s ample skeg helps it track well in windy conditions.

In the solo rowing position handling is excellent. A complete 360-degree turn takes me 10 strokes, pulling one oar while backing the other. Being double-ended at the waterline, the boat is well mannered in both forward and reverse. I have threaded narrow courses through shallow, rocky pools below seasonal waterfalls with complete confidence in the Whitehall.

Michael Reinhart

Michael ReinhartThe maximum recommended capacity for the Shenandoah Whitehall is 600 lbs, so there’s plenty of freeboard with two adults and a child aboard.

With a guest, I move to the forward thwart to maintain trim and the resulting space between rower and passenger is just about ideal for a relaxed conversation—we’re also precisely close enough to pass each other extra-tall beverage cans (regular cans will not span). When I’m rowing in the bow, the Shenandoah is a bit more inclined to yaw, probably because I’m 60 lbs heavier than my usual passenger and sinking the bow deeper than the stern. With more hull immersed in the water, it’s also a bit harder to turn. I got used to the difference in a few hours and I don’t mind it, but I do notice.

Even with the added stern sheets and lumber thwarts, my Shenandoah is light enough for me to carry and cartop singlehanded. I take help when I can get it, but I don’t dread moving the boat myself.

Perhaps the most common concern I hear is the durability of the painted fabric hull: How has it held up to beach launches, minor collisions, and the indignities of cartopping? It’s just not an issue. There are several skin-on-frame torture tests on YouTube that demonstrate the strength of this type of boat. They endure blows from the claw side of a hammer just fine. The only dings on my paint memorialize bumps on land, usually made when I smack into something while carrying her to a launch. None of the wounds leak a drop. I take care to make delicate landings, but I don’t lose any sleep about it.

After a few months of picnic rows, exploration, and a camping trip, I’ve only scratched the surface of what the Shenandoah Whitehall can do. Sometimes I’m so impressed with its abilities that I think of it less as a boat and more of an aquatic four-wheel-drive pickup truck—something to throw everything into and ride off to the next great adventure.![]()

James Kealey lives and teaches in Richmond, California. When he’s not chasing his toddler, he can usually be found banging away on some project in his garage workshop. In high school, he rowed in racing shells. He still gets away most summers for sail-camping trips on mountain lakes.

Shenandoah Particulars

Length: 13′ 6″

Beam: 46″

Weight: about 55 lbs

Maximum recommended capacity: 3 adults

Plans for the Shenandoah Whitehall are available from Gentry Custom Boats for $68 for printed, $55 for digital.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Great job on a beautiful boat. Gentry’s designs offer a very economical entry into boatbuilding and I’m sure will continue to capture a loyal following for years to come.

I am currently wrapping up work on one of Dave’s Chuckanut kayaks. I hope to have it in the water soon. The Whitehall is very high on my list of boats I want to build.

Hi James, I am taking two months off this October to build one of these in my yard. I also have a pile of walnut logs drying which hopefully I can get some parts out of. I want to experiment with older rowing fittings like thole pins or kabes and I was hoping that I could insert different styles temporarily as you say you did with your forward oarlocks. Are there any more details you could share about how you fabricated those?

Greg, the short answer is that I wouldn’t recommend doing what I did – the oarlocks weren’t that useful and will absolutely not last.

Here are some options that might send you in a better direction.

If I were doing it again, I think I’d lay up thin veneers to make what is basically a piece of plywood with a 90-degree bend. (Imagine taking a flat piece of 1/2″ ply about 2.5″ X 20″ and bending it over your knee to make a right angle.) One end of this would get the oarlock. The other end would drop through a space in the gunwale and tie into some kind of lower structure. I’d build up and shape the outrigger so that it neatly fit into the gunwale hole—there’s a lot of force being transmitted.

Best of luck with your build!

Can you provide a sketch of the stern seat modification you did? Or a verbal description. I’m about to start my own Whitehall.

I would like to add, now that I have finished and spent a season using Gentry’s Chuckanut 12s kayak. The only hole I managed to put into it was on a boat ramp. I put her down in knee-deep water, climbed in, and a passing motorboat pushed me up onto the concrete. In maneuvering off, I managed to rub through the canvas in one spot.

When I build the Whitehall, I would be tempted to add a stainless or brass rubbing strip from stem to stern to give her that more shippy look and alleviate the chances of grounding and grinding.

Is anyone aware of any lapstrake versions of this design?

I like the lines and size, but not the skin so much.

Yes, Iain Oughtred has a 12′ skiff called the Acorn, beautiful little boat, which I happen to be building right now. Can’t wait to get it done!

Funny… I have plans still (and the marine ply to build one!) for Iain’s Acorn after some number of years having passed. I built a stripper 14′ scow 50 years ago knowing sod all, it lasted maybe seven or eight years before becoming unsafe but was gangs of fun ’till that day! In late 2019 I started assembling a CLC Waterlust canoe (have plans for Ian’s MacGregor too…) launched two years later. Now I’m finding the building to be calling me once again; this Whitehall lightweight appeals in many aspects: light, easily car-topped, fast, fairly inexpensive, and not least of all very beautifully designed. I may very well order plans then dream until frost comes again in six months and I can retire to my basement shop for the winter.