The Redbird canoe has been around for almost three decades. It’s a timeless design that people just keep building. Designer Ted Moores of Bear Mountain Boats first published the plans for this boat in 1983 in Canoecraft, a handy book, still in print, that tells you everything you need to know about building a cedar-strip, epoxy-glued canoe. It includes plans for seven different canoes, including Redbird.

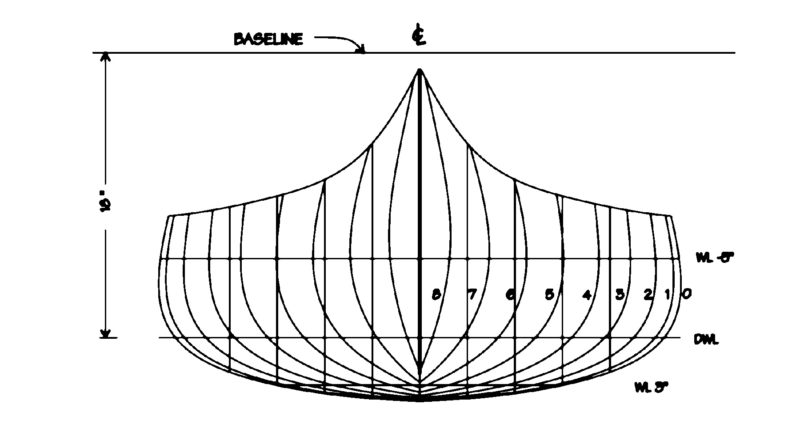

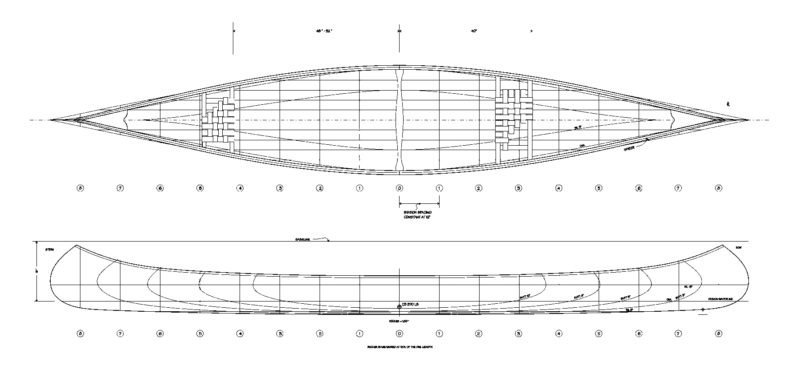

A Redbird canoe is a beautiful thing, with a sweeping sheerline terminating in boldly uplifted ends. Her fine entry widens gently into a moderate vee, giving onto a flattened U-shaped midsection. A slight tumblehome adds lateral strength and allows outwales wide enough to turn aside waves and spray. The boat paddles easily, can carry a mighty load, and tracks straight and true.

Redbird is a touring canoe, which means she doesn’t turn as quickly as more nimble whitewater models. For whitewater maneuverability you would need a canoe with more pronounced rocker. So, if you have in mind such use, with the ability to make rapid changes of direction, a Redbird is not the ideal choice. She doesn’t mind a bit of rough water, though. In his notes accompanying the design, Ted Moores writes: “The Redbird has proved execeptionally seaworthy, even in the heavy seas around the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.”

The Redbird’s sides have a modest tumblehome; this shape adds strength to the hull, and it allows for wide outwales to deflect spray. Jay Burreson built this boat.

Before continuing, I should present my credentials. I’ve had a lifetime’s experience messing about in boats, from cruising my own boats around Australia and the Pacific to round-the-buoys yacht racing. When I decided to build a canoe 12 years ago, I knew a lot about maintaining boats but I’d never actually built one from scratch; I was handy with woodworking tools, but no master craftsman. In that regard I suspect I may be a typical Redbird owner.

I chose the Redbird because I liked the look of her. I knew I didn’t want to shoot rapids, so her straight-tracking touring qualities seemed right for me. Ted Moores’s book guided me methodically through the building process, from setting up a workshop, to reading the table of offsets, making the molds, gluing up the cedar strips, ’glassing the hull, and finishing off.

All went well except for some minor flaws in the ’glass sheathing. This was not Ted Moores’s fault. His instructions are very detailed and thoroughly illustrated. He does point out, however, that “only experience can teach the proper timing” when wetting out the fiberglass cloth. He’s right there. I ended up with a couple of cloudy areas and some small patches where the epoxy had failed to soak into the wood sufficiently. I could have lived with it, but instead I decided to paint the outside and leave the inside bright. No one knows that I didn’t plan it that way.

Some Redbirds I have seen are works of art, where the builder has carefully selected the color of the cedar strips to add accents, such as a differently colored water-line or cove line. Undoubtedly, one of the most appealing things about this form of construction is that you can finish the boat bright and enjoy the subtle beauty of the wood. With a skillful ’glassing job and the recommended cane seats, a well-built Redbird canoe is akin to a piece of fine furniture.

The Redbird’s cedar-strip construction is within the reach of beginning boatbuilders—especially those who keep Ted Moores’s book Canoecraft close at hand.

Cosmetic flaws aside, my Redbird performs very well indeed. My wife and I have done several camping trips in lakes and slow-moving rivers. With a tent, sleeping bags, air mattresses, fold-up table, two folding chairs, a box of food and utensils, a cooler filled with ice, food, and drink, and a camp stove, we do not travel light. The boat has sometimes been so loaded that there has barely been room for the paddlers. Despite the extra weight, we have been able to paddle for hours on end without the trip being too arduous. Once you get moving, the momentum carries you along. Of course, I’m talking about sheltered waters, as it would be foolhardy to load a canoe like this in rough water.

Paddling two-up without a cargo is a sweet experience. It’s positively therapeutic to glide along close to shore with barely a sound, sneaking up on waterbirds or perhaps surprising a kangaroo who has come down to the shore to drink. I live in Australia, by the way. There are quite a few Redbirds here—and kangaroos.

Lesson number one in solo canoeing is the J-stroke. The paddler thrusts the boat ahead with the paddle. If the paddle were on, say, the port side, the boat would steer to starboard if the stroke ended with that. But, as the name implies, the paddle follows a J pattern, thus compensating for the steering tendency. Once this has been mastered, the boat tracks well—especially with two paddlers. As is characteristic of canoes of this type, paddling alone in a breeze can become more of a challenge: With the paddler kneeling more towards the center and the boat lightly laden, those high ends can make her quite twitchy.

In correspondence with other Redbird owners on Internet forums, some have commented that the boat is a little tippy. One owner added the rider that he is a big man and perhaps his seats were a little high. From my own experience I would not describe the Redbird as “tippy.” I’ve found that in rough water, stability is improved by adopting the standard canoeing technique of kneeling on the bottom to paddle, thus lowering the center of gravity. The difference this makes is quite remarkable.

Redbird Canoes have been built all over the world. Here we see one built by an American diplomat, Jack Diffily, in Belize; the boat is competing in that country’s distance race, La Ruta Maya.

My Redbird weighs about 65 lbs, which makes portaging theoretically possible. I confess that I never have done this, and I wouldn’t like to try it. I think it would be hard work.

Cedar-strip construction can take a lot of punishment. You would have to hit something really hard, such as a rock in fast running water, to hole the hull. If the worst happens and you do hole the canoe, there is a section in Canoecraft devoted to repairs.

Redbirds have been built in the most unlikely places. Jack Diffily, the U.S. Chargé d’Affairs at the U.S. embassy in Belize, came across a copy of Canoecraft at his previous posting in Togo, West Africa. He helped a buddy build his Redbird, and when Jack was posted to Belize he took a bunch of cedar strips and ash with him. Using Ted’s book he built a Redbird of his own.

Jack paddles the canoe on the Belize River. For the last two years a team of American and Belizean embassy staff have entered the Redbird in the annual La Ruta Maya. This is a 180-mile race held over four days on the Belize River. They came sixth in the pleasure craft division out of 76 finishers. Like me, Jack has been delighted with the canoe’s performance. And it’s had an unexpected benefit. “I had no idea the canoe would be such a catalyst for pulling our Embassy folks together and for so many people to have so much fun along the river.”

It’s hard to say how many Redbirds have been built. Certainly hundreds; probably thousands. The sheer number of them in use all over the world is a testament to the design.![]()

The Redbird has a moderate amount of rocker to its bottom, no keel, and a relatively long waterline. These traits combine to makes the boat fast and responsive—though not as nimble as a whitewater boat.

Particulars: LOA 17’7 1/4”, Draft 4”, Beam 33 1/2”, Weight 50-60 lbs

Plans and kits for the Redbird are available from Bear Mountain Boats. Canoecraft is available from Bear Mountain Boats and The WoodenBoat Store.

I built the Redbird back in 1998. It was a beautiful canoe, but as I came to realize, it was too unstable and had too little freeboard for any serious tripping.

I’m building the Chestnut “Prospector” this winter as an heirloom for my son and grandson. I had intended to build it before, but was so moved by the beauty of the Redbird and Tex’s description of it that I changed my mind. It’s great for calm waters and experienced paddlers, but the “ Prospector” is much better for various waters, a load of food and gear for a week on the water.

Different strokes for different folks, I guess. Serious tripping requires lightening the load for portaging, as well as speed. If you do that, the Prospector leaves a lot of extra freeboard which creates windage. I guess if you hunt moose, you would need the extra depth.

I designed a Redbird improvement with longer decks and more tumblehome, not greater depth. It’s been hundreds of miles through Canada lakes, and I still wouldn’t change the sheer height. My design weighs only 55 lbs. “Tippy” depends on the load and the paddlers.

I built a Redbird in 1992 and have enjoyed it thoroughly over the years. I have three girls so I made them a center seat and paddles so they could enjoy it also. When one was being difficult she went behind my seat. I have refinished it a couple of times over the years. Having purchased a solo Kevlar. I don’t paddle it much any more and is on display at our Aviation museum attached to the floats on one of the displays.

My wife and I built a Redbird in 1990. My grandsons are now paddling it. You are not building a canoe when you build a cedarstrip canoe designed by Ted Moore. You are building a legacy. My daughter and son-in-law got engaged in that canoe. My son and I still terrify each other about the time we tipped the Redbird in Astotin Lake, Elk Island National Park, Alberta. A thunderstorm was coming. I yelled “Pull!” We both dug in on the same side. The canoe flipped. The lake was full of leeches. Get your butts off the seat and kneel properly in a canoeist stance. Seats were too high. We have beautiful pictures of floating with the Redbird down a glacial green North Saskatchewan River. The Redbird tracks beautifully, speeds along with minimal effort and looks like art. But it is also tougher than nails. Dropped it off the top of car going 70 km/h. Dragged the nose down the asphalt highway. Took it home. I had skinned the epoxy and fiberglass at the bow down to the wood. Smoothed it, covered it with a fiberglass patch. You can’t find the repair. Try that with your Kevlar, aluminum, fiberglass canoe. Like the author I squeegeed a bit too hard and starved the fiberglass of expoxy. Sun eventually revealed the blotches. Now building two kayaks from Timber Boatworks (Solace 16XL and Anuri 16). Launching in May 2023

I built a Redbird back in 1995, my first-ever build. I read the book over to cover three times before I started as being a novice it was critical. I used the book offsets to layout each section station on a CAD system overlaying each section and locating a construction datum hole at the same level in each section as I didn’t like the method of aligning each section mold given in Canoe Craft. Using a construction hole in each section allowed me to run a string through each hole, centering it in the hole to insure both vertical and horizontal alignment of the sections prior to screwing the section mold to the strong back. It worked perfectly. It is very fast in the water and cuts through waves as opposed to rolling on a wave like a flat-bottomed canoe does. It is also very fast to dump an inexperienced paddler, so place the seats as low as possible and/or canoe on your knees. This “bird” always draws “lookers” where ever you paddle so be ready to explain it a dozen times during an outing.