Peter Lamoureaux, a strong oarsman, commissioned his friend John Brooks to create a pulling boat that he might race and then, after the competition, row out to an island with his wife for a picnic. The resulting Peregrine 18 has proven fast, easy to row, and handsome.

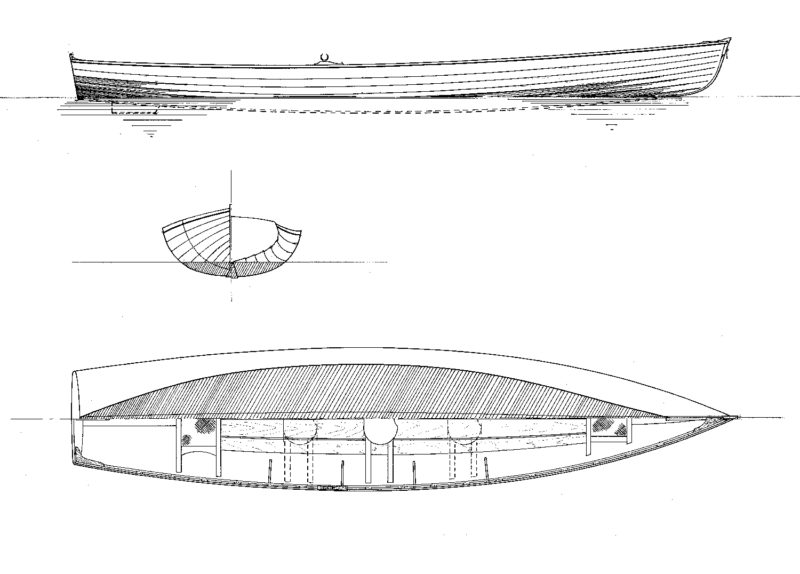

Preliminary sketches indicate that this design began, more or less, as a Whitehall boat; but the finished drawings reveal something quite different. The designer’s friend and client needed a boat that could average about 6 knots around a 3-mile racecourse, which included tight turns, in sometimes choppy water. He started by drawing a nearly semicircular mid section for low wetted surface. Highly flared sides would increase secondary stability, and they would provide a spread of nearly 4′ at the rails for the oarlocks. Brooks reckoned that a working waterline of about 18′ would offer the optimum length for an athletic one-person-power engine. A shorter waterline would waste energy through excessive wave generation. A longer boat might suffer from too much wetted surface and hull weight.

In order to reduce wetted surface yet more, and to allow for quick turns at the marks, he introduced a little rocker (convex longitudinal curvature) into the keel. For the same reasons, he drew a short skeg with an end plate running along its lower edge. This arrangement provides adequate directional stability at speed, yet it stalls readily during tight turns. In this circumstance, stalling is a good thing.

Peregrine shows a wider, flatter run than many pulling boats. Brooks wanted to provide adequate bearing to support the strength of the oarsman and the added weight of a passenger and picnic basket. That is, he ensured that this boat will not go down by the stern while being rowed at maximum speed or when loaded with wine, cheese, and cookies for an afternoon on the islands. He concluded the hull with a heart-shaped transom—no less elegant for its greater-than-usual breadth.

Robin Jettinghoff

Robin JettinghoffWith an installed, adjustable sliding-seat outrigger unit, Peregrine can meet the demands of an athletic oarsman seeking the sporting challenge of open-water rowing.

As for hull construction, the designer suggests that we plank the glued-lapstrake hull with 4mm-thick plywood if we intend to race, or 6mm-thick plywood if we seek more casual recreation. Perhaps contrary to our first thoughts, heavy pulling boats might hold some advantages. Any waterman will tell you that a heavier skiff provides a steadier platform for fishing and hauling traps. Inertia can prove helpful, and a good robust skiff will take little notice of small waves and can carry (glide) impressively between rowing strokes. L. Francis Herreshoff argued persuasively on the pages of The Rudder and in his books on behalf of heavily built human-powered boats. Yet, all else equal, the light boat usually will win the race.

The glued-lapstrake construction makes good use of epoxy and high-quality plywood, and it results in a light and elegant hull. Despite the thin planking and paucity of transverse framing, Peregrine feels strong. There is some flexibility, but it’s a lively elastic flexibility rather than the wet-noodle limpness of a plastic kayak. Full-sized patterns come with the plans package (no true lofting needed), but we’ll still want to take great care with lining off the strakes. The shadows cast at the laps should accentuate the sweet lines of this hull. If even one plank droops or is pinched, that flaw will catch our eye now and forever.

Robin Jettinghoff

Robin JettinghoffLight glued-lap plywood construction makes Peregrine’s interior very clean, with only enough framing to support her seat risers.

Thanks to the strong gap-filling nature of epoxies, the building of glued-lapstrake hulls rests well within a neophyte’s capabilities. Yet those builders not brought up with the technique will benefit from a careful read of How to Build Glued-Lapstrake Wooden Boats (WoodenBoat Books 2004), which Brooks wrote with his wife Ruth Ann Hill. Some of us will want to build Peregrine in traditional lapstrake fashion and plank the hull with cedar. That’s fine, but we’ll need to add sufficient transverse framing to keep the pleasantly aromatic wood from splitting at the laps.

On the water, Peregrine behaves as promised. I rowed the boat along the Maine coast on a clear sunny day with just enough breeze to raise a slight chop. She pulls easily up to a comfortable cruising speed. The winged skeg keeps her rock-solid on the desired course. Yet, for an 18′ 2″ boat, she can change direction quickly at low speeds. Wheeling around racecourse marks or working into a crowded float should pose no undue problems.

Joe Thompson

Joe ThompsonHer waterline length makes Peregrine a stable rowing platform, creating little wake and avoiding any “hobbyhorse” motion as the rower’s weight moves forward and aft.

After I exceeded cruising speed, perhaps 3½ knots, the hull absorbed all the strength I could muster. The harder I pulled, the faster Peregrine went. Unlike shorter and deeper boats, she didn’t squat or dig herself a hole in the water. King Kong himself likely could not overpower this hull. The boat’s owner tells of having rowed a 3-mile triangular course in a 15-knot breeze. Although not racing, he covered the distance easily at an average speed of more than 5 knots.

Peregrine seems to meet her design criteria in crisp and handsome fashion. Lightly loaded in a reasonable breeze, she travels fast when propelled by a strong rower. After the race, she’ll idle comfortably out to the islands while carrying two people and a picnic basket.

Robin Jettinghoff

Robin JettinghoffCareful attention to lining off Peregrine’s overlapping planks will enhance the hull’s lovely form. This boat was built by Joe Thompson of Brooklin, Maine, shown here at the oars.

For those of us who can’t take advantage of the 18-footer’s speed potential, or who simply prefer a smaller boat, Brooks has come up a shorter sister, the 16′ Merlin. As you read these words, he’s working on finished drawings for this design. At present he can supply a materials list, full-sized patterns for many parts, and a set of Peregrine plans (construction details for both boats are essentially identical). Although some “figuring out and reworking” are involved, several Merlins have been built using this mix of information.![]()

John Brooks specializes in the design of glued-lapstrake boats. He does business as Brooks Boats Designs. Plans for the Peregrine 18 are available for $75.

John Brooks / Brooks Boat Designs

John Brooks / Brooks Boat DesignsJohn Brooks, a Brooklin, Maine, boat builder and designer, drew the plans for the Peregrine 18 to emphasize solo rowing, with an option for two rowing stations. For racing, light 4mm plywood planking would be best; for cruising, 6mm will prove more durable. Particulars: LOA 18′ 2″, LWL 16′ 3″, Beam 3′ 10″, Draft not much, Racing weight 110 lbs, Cruising weight 133 lbs

I like the design, a Whitehall always inspired. Have you considered a small sail? My reasoning, I unfortunately damaged both shoulders, rowing consistently may be a thing of the past. I do like the idea of allowing Mother Nature to help with a traveling.