My hackles rose several years ago when I first caught sight of a NorseBoat, shining there across a well-manicured boat-show lawn. As a genial fellow exhibitor, I introduced myself to the owner and complimented him on his glossy showboat with all those strings and gadgets.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

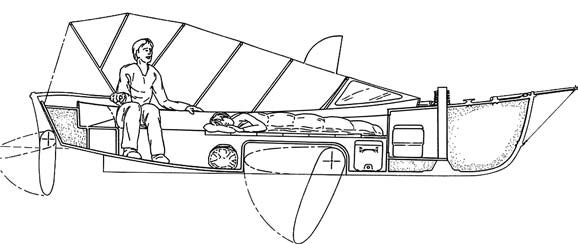

Benjamin MendlowitzThe 17’6″ NorseBoat is daysailer/camp-cruiser with a surprising range of abilities. The boat sails well, and there is ample storage for camping gear. There’s also sleeping space for two well-acquainted passengers.

As a wooden-boat builder showing a competing design, I then retreated to my traditional cave and dismissed the NorseBoat’s glistening attributes under the all-damning epithet “fiberglass.” Oh, how times change, at least for those of us willing to evolve. With five or so more years of small-boat building and cruising experience under my keel, I have now happily taken a look at the newly minted wooden kit version of the NorseBoat.

This boat requires more study time per foot than most small craft. Besides an attractive hull and an unusual sail plan, she has more bells, whistles, and unexpected features than a 1970s conversion van—certainly more than any boat in her class. What is that class? Well, perhaps we’ll call it the small camp-cruiser, intended to give two compatible adventurers seaworthy transportation for themselves and a few days’ worth of gear, with a bit of shelter and comfort thrown in.

Imagine luxury sea kayaking without the paddling or the schlepping of gear and boats up and down the beach. Imagine exploring Cape Lookout, the Apostle Islands, or the Maine Island Trail, the Keys, the Bahamas or Baja…

Designer Chuck Paine and NorseBoat president Kevin Jeffrey have collaborated on a lovely, traditional-looking hull, perhaps a little leaner than most. Her pedigree makes reference to New Jersey beach skiffs and English day boats. She’s a lapstrake daysailer, decked fore and aft, with side decks and a modest coaming. A pair of thwarts joining continuous side benches and stern sheets complete the interior. You might well daysail six people.

The high-aspect, pivoting centerboard and kick-up rudder imply her capabilities, and the lockers under her decks and benches hint at purpose, but none of these show her hand. For this, you must rig her up. This sleeper of a hull carries a radically nontraditional rig. She’s a jib-headed catboat, or a cat sloop, or something, with a fully battened gaff main set loose-footed on the boom.

The peculiarities, or perhaps better said, “distinctions” of this beautifully conceived and executed rig are legion: a two-piece carbon-fiber mast, unstayed; a fascinating curved gaff; a roller-furling jib; multiple mainsheet/traveler positions in the cockpit with a sliding strap on the boom; color-coded running rigging with matching deck hardware; the quite forward mast position and short mainsail foot which combine to allow the skipper to sail in apparent boomless luxury. This unconventional marriage of hull and rig has engendered a really fine sailing boat. She’s handy, responsive, quick, and very close-winded.

The jib is far more than the amusement I suspected it to be; it contributes significant power. The boat was noticeably slower on the wind when the jib was furled. Conditions on my trial sails didn’t warrant reefing, but she was well set up for quick and convenient reefing, and the full battens would contribute to manageable furling. NorseBoat’s savvy attention to detail becomes more apparent when considering the livability of the hull. Jeffrey has either experienced or cleverly anticipated the many travails of the small-boat cruiser.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

Benjamin MendlowitzA two-piece, unstayed carbon-fiber mast, along with a roller-furling headsail, mean minimal setup time for the NorseBoat. She can be trailered to just about anywhere and set up quickly for a camping expedition.

Storage is ample in the form of both closed lockers under the decks and open bays under the side benches. Pack in a few dry bags and stuff sacks, and all your gear has a home. Shelter has been provided in the form of a bimini aft (on a 17′ boat!) and a dodger forward, and both can be rigged while sailing. At anchor or on the beach the two combine with a zipon tent to make living aboard a dry, warm, and bug-free idyll.

So where do we sleep? Stowable filler boards drop in to bridge the thwarts and side benches, creating a sleeping flat of a size that will seem more than reasonable to companions willing to share a two-person tent, with the added luxury of a contiguous sheltered living space in the sternsheets. Further thoughtful details abound. Particularly keen are the brackets mounted on the transom that allow the oars in their sockets to be swung aft and lashed outboard, out of the cockpit and out of the way.

Subjective impressions? NorseBoat is perfectly stable in that hard-to-characterize small-boat way. She’s initially tender; where you stand and sit matters, but she is not going to turn over at the beach or mooring. I stood on the foredeck under sail in light winds with no great need of artistry or athleticism. Rumor has it that one can stand on the side decks as well.

She is billed as a sailing and rowing boat. She can, indeed, be rowed, but she is not a fine pulling boat. She’s far too heavy for that, especially when you imagine her loaded for her intended purpose. She rows reasonably, but not fast. If you’re becalmed and on a schedule (silly you…), I suppose you might make a passage under oars, especially rowing double. Fortunately, she is such a fine sailer that the oars will be mostly harbor auxiliaries. I certainly cannot imagine complicating her life or yours with an outboard motor.

While on the subject of oars, that clever storage setup is great for nights at anchor, but not while under sail. A skipper scrambling to sit up to trim a heeling boat will find herself perched on a rather stressed oar loom rather than the washboard, testing spruce, bracket, and bum. The wooden mast hoops appear anachronistic on a fully battened sail, especially on the carbon spar. Maybe it’s just the mixed media catching my eye, but the hoops seemed oversized and allowed a large range of motion in the luff of the sail relative to the mast. The main needed to be coaxed to the lee side of the mast after tacking, like many other fully battened rigs.

Finally, that distinctive curved gaff is… mesmerizing. It strikes a magnificently natural line when viewed from the helm, organic, fair and powerful. When viewed from ashore, however, or from a passing boat, it looks merely unusual. I cannot decide if it doesn’t look right just because it is different, because the mast is so far forward, or perhaps because it just isn’t quite right. No need to quibble, I suppose.

Courtesy NorseBoat

Courtesy NorseBoatNorseBoats can be purchased at various level of completion. This one is a production fiberglass model. The boat carries an outboard motor—a complication that many camper-sailors will want to avoid, as the boat is easily propelled by oars that stow on the side decks.

One of the greatest fascinations with the NorseBoat has to be that it is available as a kit, as well as partially or completely assembled. It is certainly the most capable and complete camp-cruising kit package I know of. The demo boat I sampled was beautifully put together by Dagley’s Boats, the Nova Scotia shop producing the kits. Materials and hardware were well selected, and methods and techniques were logical and appropriate.

Certain caveats must be offered, though. The kit manual and DVD were unavailable in time for this review. With the complexity of this project, the quality of those instructions will be critical, especially with an $80-per-hour meter running on the customer support phone. Boaters and builders tempted by this great boat will need to shop deliberately. Carefully read and consider the specifications and pricing. Hull components, sailing rig, oars, and accessories are priced and packaged in various combinations and options. I don’t suspect that there is any intention to mislead, but the marketing copy merits fine analysis to understand what you are getting for how much.

And yes, Virginia, some boatbuilders dare to try to make a living. Don’t be shocked that the price of a kit is more than the cost of five sheets of plywood. There are a variety of small wooden boat designs that serve as very able camp-cruisers. Graham Byrnes’s Core Sound boats, Iain Oughtred’s Caledonia and Ness Yawls, and Arch Davis’s Penobscots are a few successful ones that come to mind. Sailors interested in such boats can build them, or have them built, then spend time (some of it amusing and pleasurable indeed) designing, fabricating, and rigging all of the comforts that will make a campcruising adventure a pleasure.

The NorseBoat is a complete, well-conceived, and well-executed package that will save all that time and trouble. Let’s get one and go play boats!

NorseBoat Particulars

LOA: 17′ 6″

Beam: 5′ 2″

Draft: 9″/3′ 1″

Displacement: 530 lbs

Max. load: 1,090 lbs

Sail area: Main: 105 sq.ft., Jib: 34 sq.ft.

NorseBoat’s sail plan is distinguished by a curved wooden gaff.

The accommodations are enclosed by a sloping tent, which provides considerable headroom aft.

For sleeping, short boards fill in the spaces between the seats and thwarts; these boards stow out of the way when not in use.

For information on kits and finished NorseBoats, contact NorseBoat Limited, RR 1, 241 Point Prim Rd., Belfast, Prince Edward Island C0A 1A0, Canada; 902–659–2790, Email: [email protected].

This is a well writen article and can confirm many of the observations noted. As a professional Naval Architect and NorseBoat owner and sailer since 2009, I do have some thoughts of my own. I sail mostly “Redwing Blackbird” on the Northumberland Strait between PEI and NS. I would add that this boat is also a cousin to some for the Norwegian inshore rower/sailer designs of old. It is open salt water and full of currents, whacky winds, and shallows. I love the fact she has decent freeboard and the hull form handles a nice chop with ease. She is an exillerating sailer will handle very well in a stiff breeze. However, the standard rudder is too small for light airs in a current. I actually redesigned the rudder twice for this boat, once for Mr. Jeffries as a shoal rudder and again for my self as bigger deep rudder. Both use a NACA 00 cross-section although the shoal rudder had to be modified to accommodate the geometry. The bigger difference is the actual surface area. The standard rudder is quite small and does not follow the rules for ship construction as a percentage of projected hull area. That is an area where considerable improvements could be made to the design. The second thing I noticed is that some of the joints, although beautifully executed following moulded-composite construction methods, rely too much on the strength of the epoxy/sawdust composite radii – especially under shear loads. I have had to carry out repairs to three failures of that type in mine. That may not have been the intention of Mr. Jeffries’ original design when I look at the cross member forward of the centreboard box in the picture shown in the article and may just be a simplified approach to construction with builder not realizing the consequences. Anyway, enough griping, I LOVE my boat, especially the furling gear for the jib. It makes for awesome singe-handed sailing and would recommend it to anybody interested in a very capable design for use inland or on open water. CONGRATULATIONS TO Mr. Jeffries and Mr. Paine for coming up with a truly unique and successful example of new meets old.

PS. It survived a multiple rollovers on the trailer during Hurricane Fiona in 2022 with basically no damage. The rollovers were so violent, one of the tires was actually broken down on the wheel rim.

I have long wondered how slippery rope grommets (as in nylon slippery) would work instead of wooden mast hoops. Has anyone tried this?

Also, I think end plates for shallow rudders (à la Phil Bolger) would be worth exploring.