Have you noticed all of those kayaks riding along atop cars and trucks on their way to waterborne adventures? Their owners have seen the light. These slender double-ended boats require little initial investment, not much maintenance, and can be put on the water in seconds. In them we’ll cross open water, and when we get to the other side, we can follow an unspoiled creek to its source deep in the woods…far from the everyday annoyances of an intensely populated shoreline. Along the way, we’ll rest in shallow coves and watch as the life struggle of the bottom community plays out like a movie six inches below.

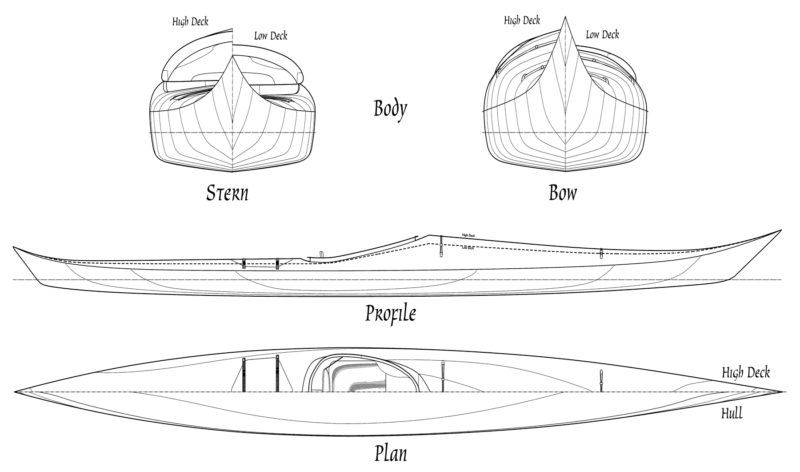

Nick Schade, a highly regarded designer-builder of kayaks, works out of Glastonbury, Connecticut, where he does business as Guillemot Kayaks. The inspiration for the Night Heron came from his ventures into rough water. The striking 18-footer is fast, able, and more stable than its 20″ breadth might suggest.

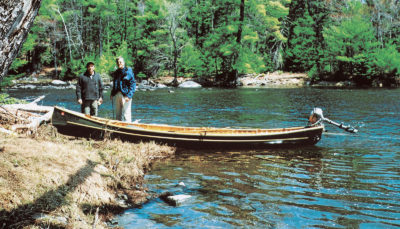

On a clear day in late summer, Nick stopped by at the WoodenBoat waterfront here in Brooklin, Maine. His Subaru Forester carried two bright-finished strip-built kayaks of his own devising: the Night Heron and the longer, wider (19′ 21″) Expedition Single.

Photo by Edith Royce

Photo by Edith RoyceThe Night Heron kayak is fast, narrow, and voluminous—a rare combination of good traits in a single boat.

Night Heron is a striking boat. Its ends sweep up in the style of native Greenland kayaks, and the edges of the decks are well rounded over. This is an organic creature…alive to our eyes. The designer explains the lack of sharp rails: “Sheer clamps ease construction; but after we’ve put the boat together, they’re just more weight to carry around.” The rounded-over “rails” reduce the chance of rapping our knuckles when working with the paddle held low. The lack of sharp edges lessens the possibility of tripping and rolling should we get caught abeam

in the surf.

We launched the boats into a rising 8-knot breeze out of the southeast, which allows a fetch that stretches to somewhere on the coast of Africa (if one discounts a few small islands). Heron’s sharply raked coaming (high forward, low aft) eases entry into the 31″-long cockpit opening. Still, the larger and less flexible among us might choose to lengthen the opening to about 36″—one of the benefits to building our own boats.

Despite its rounded-all-over appearance above the waterline, this kayak has what amounts to a V-bottom with radiused chines; and the hull’s volume is carried well out into its ends. For its type, Heron has what the naval architects would refer to as a “high prismatic coefficient.” The rest of us simply will say that the boat paddles more efficiently at relatively high speeds and shows surprising stability.

Photo by Steven E. Gross

Photo by Steven E. GrossBecause of its rounded chines, the Night Heron can be built in strip planks or stitch-and-glue plywood. Strip planking allows a fair amount of creative design, as seen on the decks of this example.

When leaned, Night Heron stiffens quickly. Left to its own devices, the boat wants to spring upright firmly but not suddenly. When we reach the angle at which positive stability disappears, it departs gently and predictably. There’s no catastrophic transition that might leave us eye to eye with the local fish population.

Night Heron moves easily through a chop. It seems to throw more spray than do round-bilged, needle-sharp kayaks; but most of that spray stays low and away from our faces. Anyone who thinks he can remain completely dry while sea kayaking might consider taking up croquet.

This kayak’s sense of directional stability is strong, but not overwhelming. It likes going in a straight line, yet turns easily—particularly when leaned. No rudder is needed. No skeg is needed. Nick Schade got it right. Let’s not tinker with perfection. Too often, rudders seem fitted to kayaks in an attempt to overcome poor hull design and/or incompetent paddling technique. Rudders are expensive, prone to failure at inconvenient moments, pick up pot warp and weed, and often result in weak and imprecise foot braces. Good single kayaks in the hands of competent paddlers do not require rudders— no matter what the sales brochures might suggest.

As Nick and I paddle across Eggemoggin Reach, the Expedition Single and Night Heron seem to achieve about the same top speed. The smaller Night Heron requires less effort to propel at all speeds and much less effort at full throttle. The bigger boat’s greater wetted surface likely accounts for some of the difference, especially at low and moderate speeds. As we approach maximum speed, Heron’s slightly convex waterlines (and higher prismatic coefficient) prove more efficient.

Choosing the proper kayak for each of us seems more akin to selecting hiking boots than shopping for a boat. We don’t sit on top of a real kayak, we sit in it. After finding the boat that comes closest to a perfect fit, we’ll adjust the accommodations with strategically placed foam blocks and sheets. The fit should be snug but not too tight. Secure contact with the boat allows us to lean, brace, roll, and accomplish all of the other maneuvers that bring joy and safety to paddlers.

Photo Courtesy Guillemont Kayak

Photo Courtesy Guillemont Kayak“Choosing the proper kayak for each of us seems more akin to selecting hiking boots than shopping for a boat.”

We’ll want to choose the type of construction that’s compatible with our building skills and patience. Nick helps us by offering plans and kits for several different Night Herons. The original design specifies strip-composite construction for hull and deck. Most of us will elect to build this model with bead-and-cove strips. These strips self-align along their edges. They mate well at various angles, which eases and quickens assembly. We’ll cover the whole boat, inside and out, with fiberglass cloth set in epoxy. Nick’s book The Strip-Built Kayak (Ragged Mountain Press, 1997) illustrates the procedure in clear fashion.

Those of us with larger than average feet (or who simply require more room for lunch or camping gear) might consider building the high-decked version of Night Heron. It’s not quite so sleek as the original, but….

Paddlers for whom launching day can’t come too soon, might select the stitch-and-glue Night Heron. As the name suggests, we’ll stitch together (with wire) and then glue (with epoxy and ’glass) pre-shaped plywood panels. The stitch-and-glue boat has exactly the same profile as the strip-built original. As built, it tends to track a little more stiffly than the stripper due to sharper deadrise (V-shape to the bottom) at both ends of the plywood hull. Because the plywood hull has a well-defined hard chine where the bottom and side panels meet, it responds to edged turns more readily. A foredeck “chine” provides clearance when we work the paddle close to the hull, and it creates more room below. As a design device, the multi-faceted deck looks just fine. On the whole, performance of both Heron hulls seems quite similar. And, yes, we can build a high-decked stitch-and-glue Heron as well.

And there’s more: we can build something called a Hybrid Night Heron, which mates a strip-built deck with a stitch-and-glue hull. The practical sense of this combination eludes me, but perhaps some folks will appreciate the marriage of a fluid deck with an aggressively angular hull. I don’t know…seems it might be better the other way ’round. If you wish, you can build a high-decked hybrid.

Finally, we have the option of building a Greenland Night Heron. In this model, Nick has lowered the after deck to ease layback Eskimo rolls (and perhaps because it looks nifty). The cockpit opening has been shortened, but the steeper rake to the coaming should ease entry and exit. In any case, all but the double-jointed will have to jackknife into the boat.

So, there you have Night Heron: a fast, able, reasonably stable kayak that you can build at home. If well crafted, it can be achingly beautiful. A strip-built original Heron resides in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Night Heron will bring great satisfaction to intermediate and advanced kayakers. It will tolerate prudent beginners and nurture their skills. Nothing, absolutely nothing, conveys the simple joy of being afloat quite so purely as a light paddling boat…but be careful out there.

Night Heron’s slight V-bottom makes for good directional stability, while the modest rocker allows for easy turning. The narrow beam is offset by firm bilges, for good initial stability.

Plans for Night Heron are available from Guillemot Kayaks.

Kits and plans for Night Heron are also available from Chesapeake Light Craft.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Another beautiful design by Nick. He does such great work. I took a class at WoodenBoat School building a strip-built kayak, truly a great class that provided many learned techniques. Thanks for sharing this article on the Night Heron!

John Lockwood (Pygmy Kayaks) also refers to the faceted deck sheer as a “chine,” but a more descriptive term is “knuckle.” Bend your forefinger into an arch, and you can see how much better that describes that shape. Besides, it is a term with considerable historical usage behind it. A chine, properly, is the sharp (usually) angle where topsides and bottom join. There are, of course, rounded chines.

I know it is fashionable to diss rudders (I always smile to myself when a novice vows that his or her kayak won’t have a rudder), but I am convinced there is no paddler alive who wouldn’t kill for a rudder under certain conditions. I’m talking about quartering seas and wind, and long crossings, which at times can drive you nuts. Susan Conrad, who paddled from Anacortes, Washington, to Ketchikan, sans rudder, confesses to this “weakness” in describing a long crossing with considerable wind and sea. Yes, edging the boat and compensating paddle strokes can correct problematic tracking, but several hours of this can be exhausting. Thus, rudders and skegs. Yes, they have their own problems. Skeg slots love to get jammed up with gravel when you launch off certain beaches. But there are rudder designs that work well, and are not subject to the usual quirks, and foot braces can be designed to be solid even if a rudder cable should break.

I have been paddling since 1984, and have paddled the San Juans, Sea of Cortez, Alaska’s Kenai Fjords, Haida Gwai, Belize, the Bella Bella area on the Inside Passage, many trips on Vancouver Island’s west coast, and the Whitsunday Islands in Australia. I did own one boat that absolutely could not be paddled in a straight line (with the rudder parked) for more than a half dozen strokes without veering, uncontrollably and unpredictably, to either left or right. This boat (which shall remain nameless), had full waterlines aft. I laid up out of fiberglass a stick-on fairing for the stern of the boat, duck-taped to the hull, and it completely tamed the miserable behavior. I made a point of forming hollow water lines into this fairing. I am always suspicious of kayaks with full water lines aft. A friend of mine built a stripper (I don’t know who the designer was), with full lines aft, and on the maiden voyage to Esperanza Inlet (Vancouver Island) he quickly grew frustrated due to its wild steering. He sold the boat at first opportunity.

on rudders…

Some boats can be paddled without rudders,….some can’t

All boats are better with rudders!