The Nancy’s China design is a marriage of the big and the small. It’s the biggest boat you can fit in a garage and the smallest boat you would want to sleep on. It’s the biggest boat you might pull with a Volkswagen van or equivalent low-powered four-banger, displacing less than 800 lbs, but it’s fit for some pretty big water, with a sailing rig that easily spills excess wind and a slug of ballast to help hold you upright. It’s sufficiently romantic, too: salty, wooden, pretty, but built with the modern stitch-and-glue method that designer Sam Devlin of Olympia, Washington, has taken to far greater lengths during the past 30 years.

Dave Wagner

Dave WagnerAt only 15’2″ of overall length, Sam Devlin’s Nancy’s China design is meant to live comfortably on a trailer. Dave Wagner of Georgia showed how even a small boat can be fitted out as a proper yacht.

Necessity was the mother of this invention. Devlin lost contracts to build three larger sailboats when then-President Ronald Reagan froze the Federal Reserve. His customers couldn’t get loans to finance their boats, so Devlin designed a smaller, more spare boat that could be bought with cash. Soon after, First Lady Nancy Reagan paid several thousand dollars for each setting of new White House china, igniting a storm of controversy. The cost of just one place setting would pay for one of Devlin’s boats, inspiring the name Nancy’s China.

The 15′ 2″-long boat’s simplicity is typified by its sprit rig, a centuries-old throwback used by Mediterranean merchants and the fisherman in Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. A long spar runs from the mast near the tack to the peak of the four-sided sail, transferring forces high on the sail to the lower part of the mast and helping to eliminate the need for shrouds. In really big wind, the sprit can be unshipped and the sail “scandalized” as a sort of emergency reefing system.

The sprit rig also lends itself to relatively easy trailer-sailing. You step the mast—which some might find a bit on the heavy and ungainly side—unfurl the sail, attach the mainsheet, and you’re good to launch. Once on the water, you can rig the halyard and then the sprit and the “snotter” line that controls its lower end, and you’re ready to sail. A weighted daggerboard in a trunk is another simplification, with the happy benefit of making this a potential beach cruiser. Oars serve as auxiliary power. Or, a mere 2-hp outboard on a transom bracket will get the boat to hull speed in calm conditions.

The boat’s simplicity extends to its construction. No building molds are required; the boat essentially shapes itself as the builder cuts and wires together the side and bottom panels and transom. The tools list calls for little more than what most homeowners already have on hand, plus a suite of epoxy supplies and an electric sander.

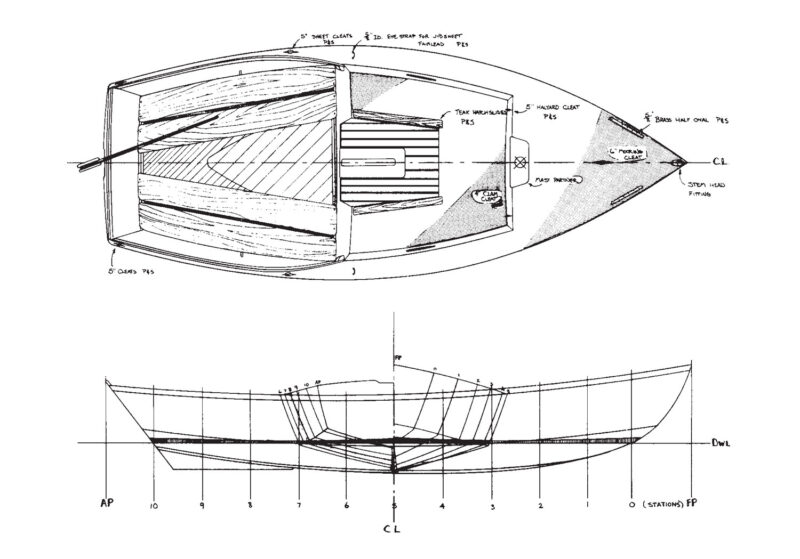

Dave Wagner

Dave WagnerHard-chine construction lends itself to plywood stitch-and-glue construction, which is the method designer Sam Devlin uses exclusively, on boats up to 45′ long. Dave Wagner set up his building form on casters so the entire boat could be easily moved.

Which is not to say this would be an easy boat to build. Dave Wagner, who may have the most tricked-out Nancy’s China ever built, spent 720 hours over more than two years building his boat. Devlin’s $85 construction plans include nine pages of drawings and a 28-page narrative. Devlin doesn’t presume you are a boatbuilder, but he does expect customers to be somewhat self-sufficient and willing to solve problems as they emerge.

“When they’re done with the approach that we use,” he says, “they’re boatbuilders.”

Would-be builders seeking an overview of the stitch-and-glue technique can read the book Devlin’s Boat Building or watch the basic technique in the video “Wooden Boatbuilding” with Sam Devlin.

I sailed a Nancy’s China for several years and it did a fine job of staving off the urge to get a larger, more complicated, and more expensive craft. I’d bought it used and a bit worn, and it turned out to be Nancy’s China No. 1. Inspired as the steward of a quasi-historic vessel, I ended up repainting every surface, replacing the seats with mahogany and doing a variety of odd jobs that, on a larger wooden boat, can become one’s sole occupation. But this is a wooden boat you can work on and sail, which I did quite regularly on Seattle’s Lake Washington.

In a way, the boat is a great template upon which to personalize a boat with minor and not-so-minor modifications. I ran the hauling part of the snotter, which is the line controlling the sprit’s tension, back to the cockpit, so I could tweak the sail’s draft—or fullness—without having to venture forward. I attached a brailing line (see WoodenBoat No. 165), which let me furl the sail up against the mast in a matter of seconds. I painted the hull green and the deck and house Bristol beige. She was a right proper beauty of a boat.

Leaning back on my oiled mahogany planks, I started seeing the boat as half-craft, half-furniture—a floating living room that was pleasant to look at and be in. I decided to call it WHIM in honor of the boat’s slight and free spirit, and the line from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Self-Reliance:” “I would write on the lintels of the something because it feels right, because it is beautiful, because it offers up visions of leaving town and work in order to fish and float like Huck Finn or spend a gusty day sprawled on the coaming like the carefree boys sailing the sprit-rigged catboat in Winslow Homer’s Breezing Up.

The Nancy’s China comes in an open, daysailer version, but I liked the original deckhouse version. It holds a lot of gear, including a portable toilet and camping supplies, and two people can sleep quite comfortably on each side of the daggerboard trunk. The house also gives the appearance of a proper pocket cruiser capable of taking one to new gunkholes, coves, and beaches far from home.

Dave Wagner

Dave WagnerYou won’t find many 15’2″ LOA boats that have interior lights, storage racks, bronze portlights, clock, barometer—and even a 4″ color television set—all of which personalize a design for a builder like Dave Wagner.

WHIM can accommodate a crew of two adults and four kids but is just as easy to sail singlehanded. I found that I could stand in the hatchway and run the halyards, or I could stand on the little foredeck to safely raise sail and hop back to the tiller. In light wind, I would steer from leeward, reducing the wetted surface, holding the sail shape, and getting my head close to the water as it swept by the neatly curved rail.

The boat’s working jib is a bit wimpy for the light airs around Puget Sound, but a genoa adds speed and serves as a gennaker with the help of a boathook in the skipper’s spare hand. In bigger wind, the boat, steadied by 285 lbs of ballast, would stiffen up before my heart reached my throat. The flat bottom can pound in rough water; but this can be solved by heeling to where the hard chine creates a V-shape that more gently parts the waves.

To windward, the boat is wanting, owing largely to the way the sail twists away from the wind at the top of the sprit. A marconi rig is likely a better close-hauled performer and one of myriad sail plan variations that would work with this design. Indeed, I regularly sailed past a gaff-rigged version moored on Lake Washington, and Devlin’s web site features five versions of the sail plan, including an aluminum-masted marconi rig and another with a deck-stepped, carbon-fiber mast. Roller furling, bronze port lights, a self-bailing cockpit—heck, even radar—are all optional, but the boat’s charm remains its simple elegance, which I spent many a moment admiring on the dock or from across the garage.

Looking at the curve of its sheer and imagining how it would follow the line of the trough it would soon be making, I sensed for the first time the fondness that makes some owners inordinately attached to their boats. And I’ve seen it in the people who streamed by to admire WHIM at the Lake Union Wooden Boat Festival at The Center for Wooden Boats in Seattle. The boat sat dwarfed by almost every other boat on the dock, but one afternoon I saw an older gentleman looking at it from a little distance. For the longest time he just stared and smiled, and I think we shared the same thought: it’s a small boat, but a boat only has to be big enough to hold a dream.

Nancy’s China Particulars

- LOA: 15 1/2′

- Beam: 6′

- Draft:

- Board up: 10″

- Board down: 6’9″

- Weight: 800 lbs.

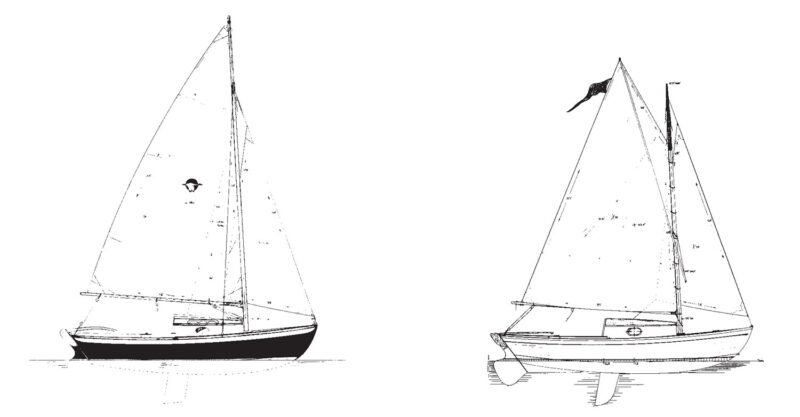

Devlin Designing Boat Builders

Devlin Designing Boat BuildersRig alternatives include a marconi sloop (left) and a similar rig with a sprit-rigged main (right).

Devlin Designing Boat Builders

Devlin Designing Boat BuildersSam Devlin of Devlin Designing Boat Builders, Olympia, Washington, designed Nancy’s China as the smallest imaginable pocket cruiser.

More information on Nancy’s China and other Devlin boats can be found at Devlin Designing Boat Builders, 2424 Gravelly Beach Loop Rd. N.W., Olympia, WA 98502; 360–866–0164.

At one time, I had the smallest C-Dory possible at 14′. It had all the bells and whistles including radar. Many larger boat owners at the dock would say “You got it right” as to size and the considerable work to maintain a larger boat. I could take this boat up many rivers and streams in Prince William Sound, Alaska by itself, not needing a rubber raft as stored on top a much larger craft. With a 4-cycle Honda 25 it burned but a few gallons a day and could be towed by a 4-cylinder vehicle.