When I was a boy growing up on Bayou Lafourche in southeast Louisiana, everyone spoke French and all the men around me were boatsmen. My uncles, cousins, and brother-in-law—all the men closest to me—made their livings with boats. Some of them were shrimp fishers, some oystermen, and still others worked boats in the oilfields. When I was 12, I wanted to go duck hunting, but I didn’t have a boat. One of those men, a shrimper and fur trapper who had built many boats (one as large as 50′), supplied me with his patterns and guidance for a pirogue, a 14′ double-ended flat-bottomed skiff made from a single 14′ sheet of fir marine plywood. In those days we could buy long sheets of marine plywood and beautiful bald cypress at a local lumber yard.

After a few more wooden skiff and steel workboat builds, I decided in retirement to build another wooden boat. I was thinking skiff; at first, a skiff à joug—a Creole skiff made from four cypress planks with a yoke (joug) for forward-facing rowing. I decided that it wouldn’t have much utility today, but I still had that hull shape in my head.

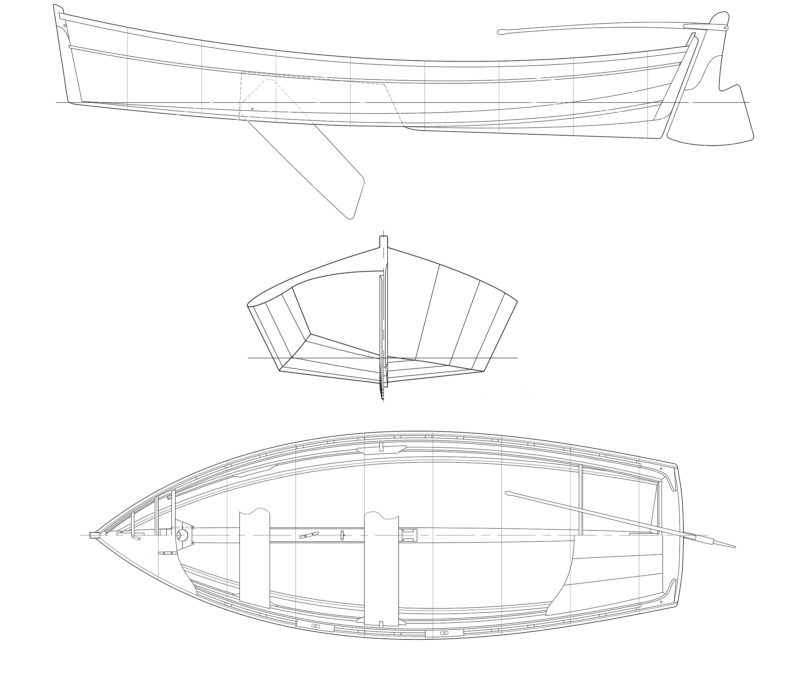

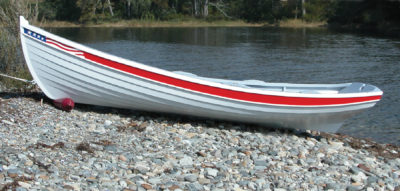

One day while searching the web, I came across a video of a skiff designed by Doug Hylan. He called it a Chesapeake Crab Skiff after boats designed for working in Chesapeake Bay. I thought, wow, what a beautiful little skiff, a working skiff much like those I grew up with. I went directly to his website and discovered that, in addition to that boat, he offered plans for a smaller version called Little Crab. I found it to be even more attractive than the Chesapeake Crab Skiff. Its profile, graced by the elegant sweep of the sheer, was just what I was looking for. I downloaded the study plans, looked them over, and I was sold. It was a gorgeous small skiff that I thought would be satisfying to build and, at the same time, help me recapture some of my skills as a boatbuilder. On top of all that, it could be sailed, something I had not done in many years and dearly missed, and it might even be small enough to cartop.

Thomas Dantin

Thomas DantinFor sailing or for sleeping aboard the center thwart can be removed and neatly stowed alongside the centerboard trunk.

I ordered the plans, and an impressive set of plans they are: five sheets including a sail plan—with spar dimensions, locations for cleats, and other attachment points—and full-sized drawings of cleats and the boom half-jaw. There are full-sized patterns for the molds, transom, and transom knees. The construction plan is highly detailed with every part numbered to correspond with specifications that give details on recommended wood species and dimensions, as well as the location of all the major fastenings (their sizes and material type are also detailed on the specification sheet). The building-jig drawing is the heart of the bundle and makes this design so easy to build. It includes full-sized templates for both the inner and outer stems, a drawing that lays out how all the molds can be gotten from a single 4×8 sheet of material, and the plank layouts. The plans set offers copious instruction on the construction of the ladder frame and the placement of the molds on it.

My Little Crab is built, for the most part, as specified in Hylan’s plans. Five sheets of 9mm BS1088 meranti plywood provided material for the planking, transom, centerboard, and rudder. All other lumber is sapele, except for the thwart riser, inwale spacer blocks, oars, and spars, which are made of bald cypress. Fastenings are as specified, either store-bought or fabricated myself from rod, bar, and plate.

I had a slight problem with the chines when offering them up to the stem. The curve around mold #1, which would become the forward bulkhead, was too tight to allow the chines to fit the stem properly. My solution was to release the mold and slide back on the ladder frame just enough to fit, glue, and screw the chines to the stem properly, then move the mold forward as close as I could to its original location. I do not believe that this changed the shape of the boat to any appreciable extent, but it is something to watch for. Another thing to look out for is fastening the bottom and sides to the chine. As you continue aft toward the transom the angle of the chine to the side plank increases, making the fastening angle critical and hard to judge. If you are not attentive you may put screws through the top of the chine (a few of mine needed to be reworked).

Rita Dantin

Rita DantinThe mast here gets stowed for trailering with one end in the transom sculling notch and the other in a notch in a specialized mast gate. The mast is designed to stow inside the boat with one end tucked under the foredeck through the bulkhead’s open access port. The storage area under the stern seat has been made watertight and is fitted with an plastic hatch.

I was unable to find rudder hardware with gudgeons that would fit the sternpost; everything I could find in bronze was too wide. The dimensions for the sternpost are not specified in the drawings, so I built it to match the dimensions of the skeg. If I had obtained my rudder hardware prior to building the sternpost, I could have set its width to fit the available gudgeons.

As for my choice of bald cypress over Sitka spruce or Douglas-fir for the spars (as specified by the plans), it was primarily one of availability in south Louisiana. Bald cypress falls nicely between the characteristics of Sitka spruce and Douglas-fir, and I know that when boatbuilders were still building spars on the Gulf Coast they were not using Sitka spruce or Douglas-fir, they were using bald cypress.

The Little Crab was designed with spars that fit inside the boat for storage and trailering. To set the longest spar, the 11′10″ mast, in the boat, the hatch in the forward bulkhead is removed and the masthead set inside the compartment.

As drawn, the skiff has one watertight flotation compartment in the bow, a stern bulkhead covered with five slats (with the center one removable for access to a storage area), and a pair of scuppers alongside the keelson to drain any water that slipped between the slats. I added a plywood top to the compartment and eliminated the scuppers to make an airtight compartment for flotation with a plastic deck plate for access. The summer I launched the skiff, I intentionally swamped it in a shallow part of the river, and found that with the two watertight compartments, the boat is unsinkable—an especially admirable attribute if sailed by a child or a senior like me. (The Chesapeake Crab Skiff has recently been redrawn with flotation compartments in the stern, and the same is being considered for the Little Crab.)

Rita Dantin

Rita DantinStraight-bladed 7’4″ oars are a good fit for the Little Crab. The drawings for the boat include a second set of oarlocks for a forward rowing station, which will trim the boat when a passenger is carried in the stern.

I was hoping the skiff could be cartopped on my old Jeep Wrangler, but I may have to admit that a 225-lb boat is too heavy for that. I bought a relatively inexpensive trailer designed for small aluminum johnboats and large jet skis. As far as trailering the Little Crab goes, it’s exceptionally light and extremely easy to launch and retrieve.

The design’s removable center seat is the place to row from. I decided to install only the set of oarlocks for rowing from that center seat, knowing that I could add the second set for the forward rowing station, if needed. That one set is enough, at least when the skiff is carrying two full-grown adults like my wife and me. I am not much of a rower, but I find the boat quite easy to row and it seems to reach its maximum speed quickly. While I was waiting for my sail to be delivered, I rowed Little Crab on several occasions for 5 to 10 miles; it was quite easy despite my lack of experience and somewhat declining tone of aging muscle. I used a modified Pete Culler oar pattern to make a pair of 7′4″ oars—a perfect fit for me.

Rita Dantin

Rita DantinThe Little Crab carries a lugsail with an area of 76 sq ft.

Oh, what a joy the lug rig is! Simple: one halyard, one sheet. It takes no more than five minutes at the launch to raise the mast, attach the halyard to the yard and parrel, rig the sheet, and go. If the halyard is led aft, all lines, including the line to lower and lift the weighted centerboard, are reachable while sitting on the bottom just aft of the removable seat.

This little boat is an absolute blast to sail. You sit on the bottom and see everything forward under the boom. Your head is only a foot or so above the water, and when the boat gets going it’s like you’re flying, and oh, that sound the water makes under and along the hull! It doesn’t take much wind to get off and the skiff can take a remarkable amount of breeze before you must do something about it. I had the 76-sq-ft balance lug sail sewn by Gambell and Hunter Sailmakers and had them put in one reef. On the day the sailing photographs here were taken, the breeze was 12 to 15 knots from the north, blowing straight down the river. The night before we had a cool front come through and a lot of rain, so the river was coming down hard. Despite the sail being poorly rigged (the clew had loosened from the boom and the foot of the sail was too loose), I was in complete control and able to tack and jibe safely; however, it was a little gusty and just about time to take in a reef.

When I sail alone, I leave the seat in its position as a thwart; when sailing with a second person, I stow that slip thwart alongside the trunk, providing more room to sit and move to windward.

Rita Dantin

Rita DantinSitting on the bottom is the most comfortable position for sailing and allows the best view under the sail.

This is a wonderful skiff: it is a good boat based on a traditional workboat of proven design. Because it is small and its low boom requires that one sit on the floor to sail it properly, I think it is best suited for someone younger and more agile than I am. It would be the perfect boat for a younger person—even a child—to learn how to sail. This little boat is simple, strong, easy to sail, and very safe.![]()

Thomas Dantin of Covington, Louisiana, is a retired shipbuilder and designer of steel tugboats and other workboats up to 115′. He worked for 40 years for the same family-owned business where from time to time he designed, operated, built, maintained, and managed a fleet of seagoing tugboats, converted a 65′ oyster lugger to a yacht, and built a few small skiffs.

Little Crab Particulars

Length: 13′

Load Waterline: 12′ 2″

Beam: 4′ 5″

Draft, Rowing version: 6″

Draft, Sailing version: 9″ board up, 30″ board down.

Weight: approx. 225 lbs

Sail area: 76 sq ft

Plans for the Little Crab are available from Hylan & Brown Boatbuilders for $100 (plus shipping). Kits are produced by Hewes & Company for $2,080.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Great article,

I’d bought the plans for Little Crab a few years back and this write-up pretty well seals the deal……I have to get started…..

Ditto here.

What a lovely boat and a great article. Thank you!

I grew up in Lafourche Parish too amongst the ship yards and trawling boats. My dad worked in a couple of the ship yards. The Little Crab and the larger 15′ version by Doug Hylan caught my eye earlier this year. It’s really neat to see that someone from the same bayou region as me picked this boat!

I wonder if the 65′ oyster lugger he converted is the WYOMING?

I’ve got one of these. Built by H&B. Although I changed the sail plan to a Crawford Melonseed Sail (62 sq-ft Sprit rig) Sail by Dabbler, oars by Dreher, oarlocks by Concept2.

Fiona is peachy.

Howard Chapelle calls this hull style (where the chines and keel batten come together at the stem) Chesapeake, or modified sharpie. Sam Rabl (as well as others, I’m sure) also designed boats with this method of construction. The advantage is fairly simple building, but with greater displacement and improved seaworthiness over a straight flat bottom.

When I was in high school I built a similar boat (a 12 footer) from a magazine article. It was kind of a crappy design, lightly constructed, but it worked, after a fashion. A clue to its crappiness was that the chines had to be kerfed toward the bow to let them take the required bend. Even in my youthful naïveté, it was obvious to me that Kerfing weakened the chines, but it was the best design available to me at the time. Of course the plywood planking stiffened it up somewhat. With a 7.5 hp outboard, it would plane at maybe 15 mph, but the engine I owned was a mid-1930s 4hp Evinrude opposed twin that I paid $25 for with strawberry picking money. Whenever I could get it running, it moved the boat at very modest speed.

After I sold that boat, I happened across a 12′ round bilge lapstrake dinghy which I bought for $40. I had to dip into college funds for that purchase. It was lovely boat, but very old and somewhat worn out. I tried to glue splines into the cracked planking, but after a spell in the water for a while (there was a small boat livery service on the lake where I kept it during the summer) it tightened up quite adequately. I also had to bend in some sister frames to reenforce cracked originals. My first venture into steam bending.

My high school buddy and I loaded the boat with camping gear and headed up Lake Chelan on a breezy, choppy day. Occasionally spray would wet the spark plugs, killing the engine, but after a wiping down, we would be running again. Our camping destination was Prince Creek, about 30 or so miles from Chelan. During the night, deer wandered through and a skunk rattled the dirty cans in our kitchen. Heading back down lake, we had the same white caps as before, but this time we had fun surfing on the following seas. It took alert steering to avoid broaching, The waves of course were moving faster than we were.

Eventually I sold that motor, shortly before it became valuable as an antique.