The Thames skiff is a lightweight, narrow, lap-strake rowing boat native to England’s River Thames. While it dates to the 10th century, and emerged first as a ferry boat, ship’s tender, and fishing craft, it became popular in Victorian times for racing and leisure. The boats ranged from about 18′ to 30′.

I live in the north of Scotland, about as far from the River Thames as it is possible to get while remaining in the U.K. So it may seem odd to think of building a Thames skiff up here. It all started when my wife and I rented a holiday cottage on the Thames and had the good fortune to visit the boatbuilders Henwood & Dean at Henley. There I was inspired by a magnificent small skiff (18′ 3″ long) recently completed and immaculately varnished, with its gold-leaf cove lines and woven cane armchair aft. I thought it would make an excellent project because it is lightweight and lends itself to ornamentation, which would provide good occupational therapy for one of advancing age and diminishing physical ability. My wife was enthusiastic too, imagining some rather more ladylike boating than that to which she had been subjected hitherto.

I took as many photographs and measurements of the boat as possible, but did not have time to take the lines, even if I had known how to do so. Fortunately, boat designer Iain Oughtred has plans in his catalog for a 19′ Thames skiff for glued-plywood construction, and I decided to build that boat—with some departures from Iain’s specifications. I used the mold shapes detailed on Iain’s plans, but chose traditional, solid-wood construction rather than plywood. And I changed the interior to my own tastes.

The Thames skiff has six planks per side, topped by a seventh, the “saxboard,” which is twice as thick as the normal planking and constitutes both the sheerstrake and the gunwale. I built my boat upside down to make it easier to fit the first few planks; I then turned the whole thing over in order to be able to do a neat job of fitting and fastening the saxboard.

The Thames skiff’s principal backbone member is formed from two pieces: the on-edge keel timber and the on-the-flat hog, or keel batten, which sits above the keel, forming a T. I chose close-grained Douglas-fir for the keel. Slender oak knees at each end of the back-bone support the stem and transom. All of the back-bone joints were glued and screwed.

KINGFISHER’s frames are 3/8″ thick, except in way of the oarlocks, where they are 1/2″. All are joggled to fit the planking. In some original Thames skiffs, the frames taper inboard in order to save weight.

I planked my boat in 5/16″ Brazilian cedar. Because the first two planks have a pronounced twist, I steamed their ends using a wallpaper stripper attached to a sleeve made from sheet plastic. This device could be passed over each plank end to allow steaming where needed, while the rest of the plank was temporarily clamped in position. The half-inch plank laps were fastened using 14-gauge copper nails and 3 /8″ roves. Because of the awkwardness of working inside the overturned boat, only intermittent nails were riveted to “spot-weld” the plank into position, and the rest were left until the boat was turned upright.

With six planks on, it was time to turn the boat over to start work on the saxboards. This turned out to be a time-consuming performance involving the removal of the molds from the strongback and, once the boat was turned over, replacing them inside the boat, realigning them, and then bracing them from an overhead beam.

The saxboards are 5 /8″ thick and have a 5 /16″ × 5 /8″ rabbet cut in the inside lower edge to fit over the top of the sixth plank so that it is flush inboard. An ogee molding routed along the lower edges of both sides of that board delineates an area of gold-leaf decoration. Given the boat’s low freeboard, the upper edge of the saxboard is raised in way of the thole arrangement to elevate the oarlocks. (For simplicity I elected to use bronze oarlocks rather than the more traditional square-sectioned tholepins.) It took quite a lot of adjustment to get the upper edge of the sixth plank to fit neatly into the saxboard rabbet the full length of the boat, but with this done and the fastenings in, I could finally remove the molds and begin the fitting out.

The majority of historical Thames skiffs were planked in mahogany. Colin Galloway chose Brazilian cedar for his boat, because he found a stash of it of suitable length and quantity. This lightweight, pale brown wood is fairly soft and rot resistant. “It is nice to work but produces an irritating peppery dust,” reports the builder.

The floor timbers span the lower three planks except at the very ends, where they are shorter. They are fastened to the hog with a central nail and normally have limber holes only at the garboard; however, I put limber holes at each plank lap, as well, to make it easier to fit the floor timbers. Furthermore, the additional holes, which allow water to pass freely through the floors, seemed a sensible addition after an experienced builder told me that one of the first things to rot in the older boats is the floors.

I set the cedar thwarts on cleats fastened to the planking and strengthened them with oak knees. Then I added quarter knees and the breasthook, followed by the framework to support the adjustable footrest for the oarsman. I made floorboards from cedar and Douglas-fir.

One of the most recognizable features of the Thames skiff is the comfortable armchair aft. These chairs sometimes have a solid wooden back with ornate wrought-iron arms, but I thought I would have a go at the woven-cane type, which looks a bit better to my eye. Brass fittings allow the seat to be assembled and taken down quickly. Two studs (brass screws with the heads sawn off) protrude from either end of the back and pass into holes on the inner sides of the arms. The arms are then held closely onto the back by hooks and eyes. The seat assembly’s only attachment to the boat is by a hasp-and-eye arrangement at the forward ends of the arms.

The final touch was a fine red velvet cushion with buttons and gold braid, made by my wife.

Builder Colin Galloway, with KINGFISHER.

I launched my Thames skiff, KINGFISHER, after two-and-a-half years of construction, on a fine June daPortsoy, Scotland. She was christened with the aid of a small quaich (a highland drinking vessel) of whisky shared with family and friends. She is not a sea boat, but it was a calm day and we all enjoyed a great outing using borrowed oars—oarmaking being a job I’d saved for the following winter.

I asked several oar and skiff builders what length of oar would be best for a skiff with a beam of 3′ 9″, but each had their own special formula, with lengths ranging from 7′ 6″ to 8′ 6″. So I decided to make the oars 8′ 6″ and allow for shortening in the light of experience. I chose Sitka spruce, and gave them hollow looms.

These 8′ 6″ oars proved to be unwieldy and did not allow enough leverage inboard. So I removed 6″ and adopted the practice of overlapping the handles during the recovery phase, and they were just right for someone with my relatively modest muscle power.

KINGFISHER uses square-sectioned oarlocks, rather than the more traditional tholepin arrangement.

In the summer of 2011, we had some exhilarating recreational rowing, mainly on Loch Ness. Most commonly there has been just one passenger, but the boat is perfectly comfortable with four aboard. She has proved to be quite fast and to carry her way well, especially in smooth water, but I would guess less so than the more usual longer (about 21′ ) and less beamy single skiff. Having a long keel with very little rocker, she is slow to turn using oars alone, but is remarkably responsive to the transom-hung rudder. I would estimate the turning circle to be around 50′. Choppy water significantly affects her performance—but, then, she is a river boat.

This Thames skiff has provided a great deal of enjoyment both in the building and the rowing, and can be thoroughly recommended as a project for anyone who wishes to have some fast and comfortable rowing in sheltered inland waters. ![]()

—

Plans for this Thames Skiff, Iain Oughtred’s Badger, are available from Oughtred Boats.

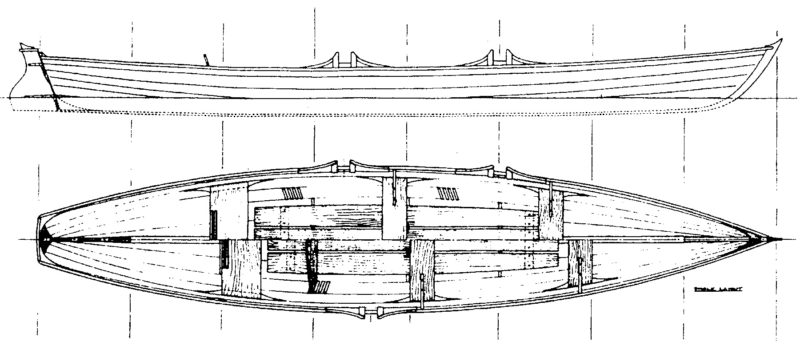

Colin Galloway built KINGFISHER to Oughtred’s Badger design, shown here, but included only one rowing station. Badger’s plans are an enlargement of the 16’ Mole; the lines plan is common to both, but the station spacing is revised for the longer boat. Thames Skiff Particulars: LOA 19′, Beam 44 1/2″, Draft 15″, Weight 150 lbs

Beautiful craft, expertly executed. A joy to gaze at!

The boat is beautiful. Where did the square sectioned oar locks come from?