Harry Bryan, a boatbuilder and designer from New Brunswick, Canada, designed the Fiddlehead, a 10 1⁄2′ double-paddle canoe, in 1992 after his sister-in-law introduced him to her Wee Lassie. The Wee Lassie is a small double-paddle canoe designed by J. Henry Rushton around 1893. Bryan had always rowed small boats, rather than paddled them. He had “never faced forward in a boat,” because rowing requires that one face aft, looking at where he’s been rather than where he’s going. This paddling business was something of an epiphany for Harry Bryan, and his fertile mind was inspired to adapt the Wee Lassie to his preferred construction techniques. We’ll come to those in a moment. First, a word about the Wee Lassie.

J. Henry Rushton was a great designer and builder of boats and canoes one hundred years ago. He conceived the Wee Lassie to be an easily portaged solo canoe—a boat that could cross a lake and then be hoisted onto a shoulder and carried through the woods. Its popularity today continues to increase; it allows a paddler to get into thin, otherwise inaccessible waters and see wonderful things from a rare vantage point. Bryan is not the only builder to have taken inspiration from this design. Henry “Mac” McCarthy, formerly an instructor at WoodenBoat School, has coached uncounted builders through the construction of these boats to his own adaptation, which uses strip planks and epoxy. With the Fiddlehead, Bryan took things in a different direction.

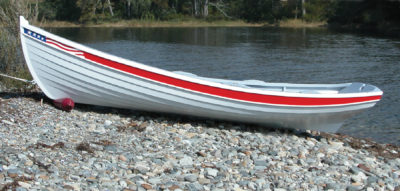

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzInspired by a 100-year-old solo canoe design, Harry Bryan conceived Fiddlehead for “dory style” construction. While the boat is meant for one person, a passenger of appropriate size can be allowed.

Bryan builds boats from a home-based boatshop that uses no grid electricity. He has a foot-powered bandsaw, a jigsaw built from the remains of an old Singer sewing machine, and a drill press operated by hand crank. His lumber is cut and milled locally (and selectively), and his choice of woods for Fiddlehead reflects that. The boat is planked in cedar and framed in spruce, with bits of oak and locust here and there, where hardwood is required. “I wanted to use dory construction,” he says, “with a relatively flat bottom and strength in the planking.” Dories have no wood keels. Instead, their narrow bottoms are the keels. Or their wide keels are the bottoms, if you prefer. The point is that there is no complex structural joinery involved in the building of a dory bottom. A solid flat surface provides the foundation for the topside planking.

The topside planking is lapstrake. This means that its edges overlap each other, like clapboard siding on a house. They are fastened together with clenched (bent-over) nails, and are supported by widely spaced frames. While Fiddleheads are good looking and worthy performers, their essence is simplicity. That’s often a tough combination to achieve in a design; usually, you get one in exchange for the other. Here’s how Bryan describes the Fiddlehead concept and aesthetic in the introduction to a manual for building the boat:

“She is simple because she is small, has a modest number of parts, and is constructed with techniques worked out over centuries of small boat building. She is elegant not by any standard devised to measure such a quality (such a measurement is impossible), but because we have observed people’s reaction to her and we know that it is so.” That’s true. I’ve observed people’s reaction to her, too, at boat shows and in workshops. A Fiddlehead always swells a crowd of smiling admirers.

The design is so simple and so alluring that, for the past several years, seventh and eighth graders have built boats to it in an after-school boatbuilding program. The program begins in autumn, in the woods with live trees, draft horses, and a sawmill; it spends the winter in a wood -heated boatshop and ends in the spring on a pond on the WoodenBoat campus.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzFiddlehead’s combination of good looks, local materials, and simplicity have made it an ideal candidate for a boatbuilding program for Brooklin, Maine, junior high school students. Here, two young builders paddle newly launched boats on a pond at WoodenBoat.

If you wanted a Fiddlehead of your own, you could order one from Harry Bryan, or you could buy a set of plans and a detailed instruction booklet from the builder and do the job yourself. If you went the latter route, you wouldn’t have to take to the woods with draft horses, but you might find yourself casting about for substitute woods, depending on where you live. The instruction booklet covers this topic: instead of cedar planking, you might use pine or spruce; instead of spruce frames, you might use ash or oak.

Many builders will wonder if the boat can be built from plywood, and Bryan notes that, indeed, it can. For planking, he says that 1⁄4″ should be about right; the bottom will want to be beefed up to 3⁄8″. The decks will be 1⁄8″, and the bulkheads 1⁄4″. There’ll still be a smattering of hardwood in a Fiddlehead built mostly of plywood.

Bryan says that his manual “assumes that you have some knowledge of woodworking tools and how to use them.” He advises a first-time builder to enlist the help of someone with experience for advice and instruction before embarking on an uncertain next step. The designer himself is available by mail or telephone for answers to technical questions.

Harry Bryan, and his wife, Martha, go camping in their Fiddleheads. There’s an elliptical opening in the bulkhead through which a tent will fit; this opening is sealed with a removable cover, to retain the watertight integrity of the bulkhead. There’s space behind the cockpit seat to fit a drybag’s worth of essentials.

The boat is self-rescuable; there are two watertight bulkheads, and these create flotation chambers forward and aft, so the boat will float high when rolled over. A person of average ability can dump a Fiddlehead and get back in from the water, and then paddle away. Bryan has done this on purpose, just to be sure. He was back in the boat, from the water, in 14 seconds, with just 1⁄2″ of water in the bottom. He did the test off of his home in New Brunswick, in the Bay of Fundy, whose cold waters provided ample motivation to speed things along.

“Because I know I can get back in the boat, I’ve gone to St. Andrews — five miles cross.” But he wouldn’t recommend such open-water venturing for everyone—only for experienced paddlers with a proven ability to rescue themselves in the event of a capsize. Besides, Bryan finds it much more fun to paddle close to shore, and observe the natural drama at the water’s edge.

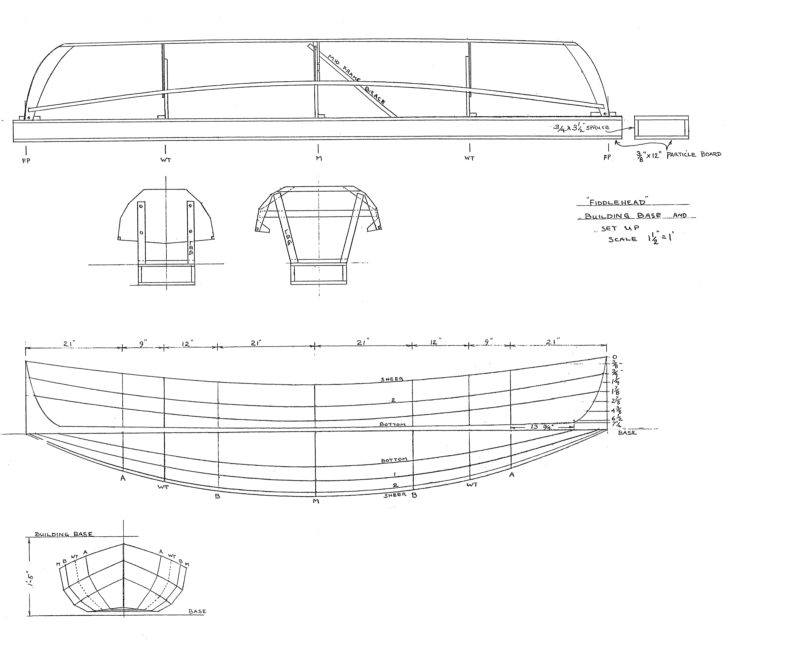

Harry Bryan has tinkered with the Fiddlehead’s design over the years, and come up with two enlargements. The first, which appeared in 1995, is a 12-footer; next, in 2000, came a 14-footer. Each plans packet includes three pages of drawings (with full-sized patterns for the bulkheads and frames) and an instruction book.

Harry has also devised several Fiddlehead accessories over the years. The plans have always included instructions for building a paddle. (Heed these words from the manual: “You could purchase a carbon fiber paddle, but I think you’re missing what Fiddlehead is about if you do.”) There’s a spray skirt, too—but not of the tight-fitting, kayak variety. This one is more like a low-slung dodger that fits over the forward coaming. “It keeps all of the paddle drip off of you and makes a huge difference in September or October,” says Bryan. There’s a sail now, too. This sail, however, won’t be set in the usual way, on a fixed mast. Rather, the inverted triangle mounts on the end of the paddle and is held aloft to provide propulsion downwind. “All of us want to open our coats when paddling downwind,” Bryan says. We do, for sure. I recall a canoe trip on Maine’s Allagash River years ago, with a strong tailwind on the last day. There were four canoes carrying eight of us, and all were standing with slickers open, looking like a fleet of little clipper ships. Oh, but for a bunch of Fiddlehead sails!

This boat will take you into the golden years. In addition to the spray dodger, a paddle, and sail, Bryan has devised a “geriatric boarding aid”—a shop-built device to stabilize the boat when boarding and disembarking. What more could you ask for: a boat with a built-in retirement plan.

The original Fiddlehead, shown here, measures 10 1⁄2′. There are now also 12′ and 14′ models. Each plans package consists of three sheets of drawings and a detailed instruction book.

Plans for Fiddlehead are available from Bryan Boatbuilding.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

It is a very cool boat for messing about. I have it on my list of boats to build.

Truly beautiful lines on the Fiddlehead. Would have loved to see some video of the boat in action. But lovely photos nonetheless. Thank you for the terrific article!