Paul Gartside’s plans for modest-sized cruising boats inspired by the Falmouth cutters of his native England should all come with one of those warnings from the Surgeon General, this one about the risks of indecision and the dangers of addiction. To look at one of the profile drawings too long leads to certain wanderings of the mind that can all too easily lead to reckless daydreaming.

You start with something simple, say his 22′ 6″ centerboard sloop, and before you know it, you’ve said to yourself, well, if 22’6″, then why not 2′ longer? And if the 24′ 6″ cutter, then why not 29′ ? Before you know what hit you, you’re looking at the 30-footer and you’ve got yourself comfortably seated in that main saloon after a fine day’s sail, anchored down in some lovely cove somewhere with a good book and a glass of tawny port.

Jim Mitchell had been through many boat design-and-construction sequences before he started thinking about one of Gartside’s designs. Mitchell’s own boatbuilding goes back to his teenage years, and he had already worked with designers and builders: many years before ELF, he had Joel White build the 45′ Pete Culler–designed scow schooner VINTAGE, and later he modified a Bill Garden–designed power cruiser to produce KINTORE (see WoodenBoat No. 140). He probably had his design-gazing habit pretty well under control by the time he started looking seriously at the Gartside portfolio.

He knew what he was after, and as with his previous boats he had a very specific goal in mind. This time, he wanted a sloop of modest proportions, something a little larger than the smallest of Gartside’s impressive family of cruising designs. But he didn’t want anything too large, either. He started off with transcontinental cooperation on adapting design No. 106 from Gartside, who lives in Sidney, British Columbia—an echo of Mitchell’s previous collaboration with Garden, who also lives in Sidney. Mitchell, who lives in Camden, Maine, redrew the plans to make the boat large enough for two (the other being his wife, Lolly) to cruise in relative comfort.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzELF is an ample and seaworthy cruising boat, well outfitted for voyages of as much as a month at a time, with such amenities as a canopy to keep the sun off the cockpit. She is small enough, however, to be moved by trailer to the next cruising grounds.

Now right here, it’s best to take note of the inclination of almost everyone who looks at boat plans to want to just change a little here, add a little there, reconfigure this, and end up moving everything around. Stock answer: don’t do it. Mitchell’s engineering background combined with a lifetime of sailing, cruising, and boatbuilding gives him an unusual skill set and an ability to communicate in the right language with the designer. He had already been through several boat construction projects (including providing some 50 design sheets for KINTORE). Even with this background, his changes didn’t represent any radical departure from Gartside’s design. Other than making the design larger by 8.333 percent, he had clear interior priorities in mind: among them a little more galley space, a semi-private head, a heater, and more storage space.

The Mitchells planned to be gone cruising for long stretches of time. They didn’t just want to cruise the coast of Maine; they also wanted to be able to go far afield— perhaps a month in the Bahamas. They wanted the boat to be small enough to just fit within the maximum legal width limits for highway trailering (although the boat must be lifted onto the trailer by a Travelift). At the same time, it had to be within the substantial towing capacities of their truck so the boat wouldn’t have to be shipped overland.

The result is a 24’41⁄2″ double-ender that is the “just right” fit for the way the Mitchells like to sail, which is to say cruising. The enlargement retains the fine proportions of Gartside’s design No. 106, including its trunk cabin profile. For a solo sailor or a couple with weekend or one-week voyages in mind, no doubt Gartside’s original 22’6″ version would suit the purpose equally well.

Mitchell was able to work out a cabin plan that uniquely suited his ideas about what ought to be the fitout for comfort and practicality for his cruising needs. Below decks, the V-berths are forward, with neatly worked-out storage lockers and shelves on each side. In the main cabin, the space is divided amidships by the centerboard trunk. Rather than getting in the way, the low-profile trunk provides a convenient perch while preparing a meal in the well-laid-out but compact galley to starboard or the navigation table to port. The navigation table flips up to allow access to a plumbed semi-private head underneath. The port side also has a locker, a useful counter with drawers under, and a cabin heater. Deck prisms help bring light below.

Photo by Tom Jackson

Photo by Tom JacksonThe practical and comfortable layout of ELF’s interior reflects Jim Mitchell’s tastes and his extensive experience with cruising sailboats.

With her cold-molded hull (built at French & Webb in Belfast, Maine), ELF’s interior volume is high for a boat of this type. Her coach roof has substantial camber, giving her good inside sitting headroom yet keeping her cabin sides relatively low so as not to throw her outside appearance out of balance.

The Yanmar diesel remains out of sight under the bridge deck, which has an access hatch, thus keeping the cabin clear of any encumbrance. With sound buffering, the engine stays comparatively quiet for a boat this size.

Over the past few years, the Mitchells have followed through on their plans, taking ELF everywhere they wanted to. They’ve crossed the Gulf Stream out of Florida, picking their weather window with care. They’ve spent a month or more at a time in their favorite cruising grounds of the Bahamas, extending their season from their usual Maine waters. The ability to tow the boat by trailer has kept open a whole range of cruising possibilities for them despite the boat’s relatively small size.

They have made very few changes over the years. For one thing, the boat demonstrated too much weather helm with its original rig. So Mitchell added 14″ to the length of the bowsprit and had a new, larger jib built. That seemed to solve the problem. Other than the usual fitting-out to make a cabin a home, they haven’t changed a thing in the interior layout and wouldn’t do so even if given another chance. The only remark they have is that the boat, after some weeks of cruising, can seem just a little too small. But if the weather’s fair, the large cockpit, rigged as it often is with a tarpaulin to keep the sun off, provides the best living room imaginable.

Photo by Tom Jackson

Photo by Tom JacksonWith pinrails at the mast base, parrels at the boom jaws, running backstays, bulwarks, and deck prisms for light below, ELF has many touches to keep a traditional sailor happy.

The gaff-headed mainsail is small enough to be manageable. Together with trailerability, the ease of handling the rig was one of Mitchell’s primary considerations in choosing a boat of modest size. This year—remarkably—Mitchell turned 80 years old, so he wanted a rig that wouldn’t tax his strength too much. The main raises easily with its throat and peak halyards.

It must be said, though, that if you’re the kind of person who goes aboard a boat like this—with its two main halyards, running backstays, and jackyard topsail—and you say rather dubiously, “Lot of lines to pull,” you might not be happy with this rig. Personally, I much prefer it. Years ago, I told someone that driving a highway at 55 mph “isn’t driving, it’s rolling.” Similarly, if I don’t have something to do with sails and lines while under way, it’s not sailing, it’s going for a boat ride. It’s just a matter of inclination and preference.

I joined the Mitchells for an afternoon of light-air sailing, which is not the best way to show the mettle of this type of boat, with its relatively heavy displacement. I had enough of a taste to know that she handles like a much larger boat—when first aboard, you’re tempted to ask whether she is a 26-footer, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the Mitchells have heard her mistaken for a 30-footer. Mitchell feels that at about 12 knots of wind speed ELF is at her happiest. She has seen much more, but she handles comfortably with the main alone in relatively heavy wind, and Mitchell says she has an uncommon ability to tack without missing stays even under just the staysail alone.

I don’t sail gaff rig nearly as much as I’d like, considering it’s my favorite rig to look at, so I sometimes have difficulty interpreting trim on a gaff-headed mainsail in very light airs on an unfamiliar boat. But I could feel that ELF moves purposefully even then. She isn’t going to win the races, but that is just about the last thing the Mitchells have in mind.

ELF has been everything the couple hoped for: seaworthy, comfortable, stable, and secure, with shallow draft giving her the ability to seek out those secluded places that keep cruising sailors willing to round just one more point of land, to find just one more perfect cove.

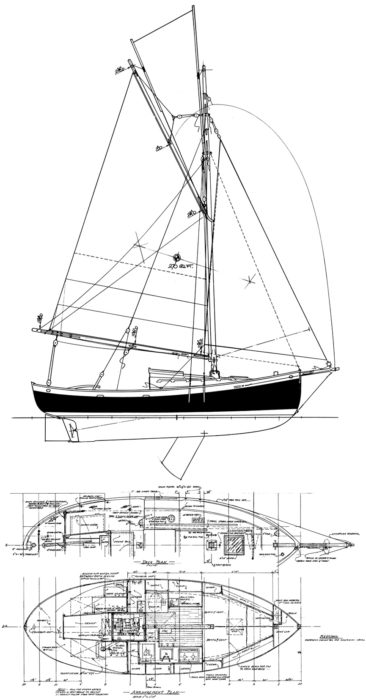

Paul Gartside’s drawings of a modest-sized double-ender caught Jim Mitchell’s eye, and working with the designer’s approval he enlarged the boat for greater comfort in the accommodations. Mitchell’s revised sail plan (right of the two above) is proportional but was revised to include a slightly larger jib set on a longer bowsprit. His accommodations revision reworked the interior a bit to include, among other things, a semi-private head and a cabin heater. Mitchell and his wife, Lolly, have extensively cruised the boat, which they can haul on a trailer.

Plans for Paul Gartside’s original 22′ double-ended centerboard sloop, (No. 106), are available from the designer’s website.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2007 and appears here as archival material. If you have more info about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Stunning – hurts knowing that is not my life. Beautiful part of the world and pretty boat to sail all over it!

This is a beautiful boat and the layout is interesting to look at, knowing that countless hours were invested in getting things right. (I would never have thought to put the semi-private head under the chart table, and it is certainly more “semi” than “private”, but mentioning it has a purpose: the the over-use of the hyphen.) Though I think this is an auto-correction problem, I have to ask why the words “pro-vides”, “gal-ley”, and “fit-ting” appear in this fine article, and why they were not fixed during proof-reading. Being a slow reader who enjoys the flow of words, I find these unnecessary weird words slightly jarring when I’m savoring the wonderful articles you post. I’m going to remain a sub-scriber and avid cover-to-cover reader of your magazine, and I congratulate you on put-ting together a very enjoy-able peri-odical, but this typo thing is like the mos-quito that made it through the screen and needs to be swat-ted.

Thanks, and keep it up,

Michael Moore

Michael,

Thanks for pointing out the errant hyphens. They appear to be leftovers from the text as it was prepared for the print issue. We’ll get to work to fix the problem.

Ed.—

Lovely, lovely boat!

Wish there were more small outboard cruisers here than impractical sail boats for non-lovers of sailing. Asia has 10s of thousands of worn-out 2-cycle motorbike engines that will not change anytime soon. As you approach large cities there you can see blue cloud hanging over said cities a hundred miles out. Outboards in North America are few in number and even 2-strokes add little to the overall effect of pollution.