Ruth Hill

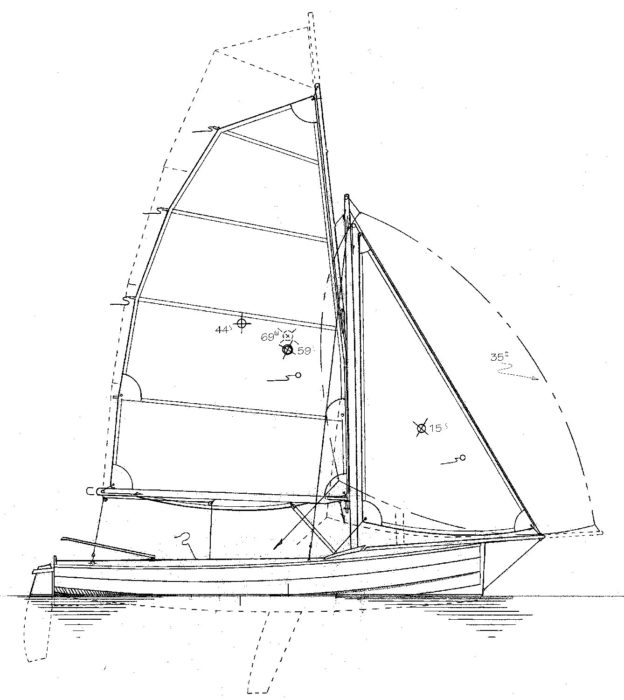

Ruth HillZIP is the prototype model of the DragonFlyer 3.2, a design intended as a versatile and dynamic sail trainer. She can be sailed with main alone, main and jib, or main and asymmetrical spinnaker.

Here we have the DragonFlyer 3.2, a brand-new 10′ 8″ sloop meant to offer training for beginners and spirited performance for experienced sailors.

Bystanders have described this particularly striking little boat as nifty, swell, cool, or awesome. The choice of adjective appears to depend upon the observer’s age. DragonFlyer comes from Brooks Boats Designs in Brooklin, Maine. John Brooks and Ruth Hill (husband and wife) run this outfit, which specializes in designing glued plywood-lapstrake boats ranging from dinghies to small cruising sailboats.

Brooks has given DragonFlyer a gunter sloop rig with a fully battened mainsail. At first glance, that main looks as if it might be a “batwing” sail pulled from a late-1800s sailing canoe. However, close inspection reveals the battens to be nearly parallel to the boom rather than splaying out in the old batwing pattern. This configuration will permit slightly better airflow across the sail and allow for simpler furling (after we release the sail from the yard).

Ruth Hill

Ruth HillDragonFlyer is easily transported from car to water with a simple two-wheeled cart.

Full-length battens offer several advantages. They support considerable roach (convex curvature to the leech). This allows more sail area to be carried by a relatively short mast, yard, and boom. The mainsail is compact, but of powerful shape.

If we wish to fuss with the full-length battens, they will give us precise control of the draft or “fullness” in the sail. We can vary the thickness of the battens along their lengths or force them farther into their pockets (to produce more draft), or let them project farther out beyond the leech. In any case, we might make the battens somewhat more flexible (thinner) in their forward portions, where we want maximum draft to the sail, and stiffer as they approach the sail’s leech.

Ruth Hill

Ruth HillThe DragonFlyer’s light construction and flat bottom make her easy to launch from a beach. Rigging her sails and getting her into the water take only a few minutes.

Full-length battens can almost eliminate violent slatting as the mainsail luffs. Whether this proves to be an advantage or a potential problem seems to depend upon the situation and the skipper’s level of experience. When a fully battened sail is full and driving, it wants to keep going. As we approach the float, simply letting go the sheet might not slow our boat as quickly as we fervently hope. We should keep this in mind, lest we wind up in the parking lot next to a Buick.

The sail plan shows that we can step Dragon Flyer’s mast farther forward and sail her as a catboat. Brooks believes this will prove popular with novice skippers and smaller children. A noble idea, but as a long-ago little kid myself, I’m inclined to think that many youngsters will want to fly all sail possible all the time. They might well leave the conservative cat rig to their parents.

That cat rig, although simple to sail with “only one string to pull,” might prove more difficult to sail really well. Fully battened sails tend not to telegraph notice of improper trim so quickly as unsupported (slatting) Dacron. With no headsail to direct airflow, we’ll need to pay close attention to the single sail’s sheet. In the beginning at least, let’s tape a forest of telltales to the sail.

At the other end of the scale, we can move the bow-sprit to its full-forward position and fly an asymmetrical (single-luff) spinnaker. For the truly adventurous, Brooks has drawn an enlarged sloop-rig option. He describes the overall rig as “simple, affordable, and fast.” Well, it’s certainly versatile as we can set several different combinations of sail.

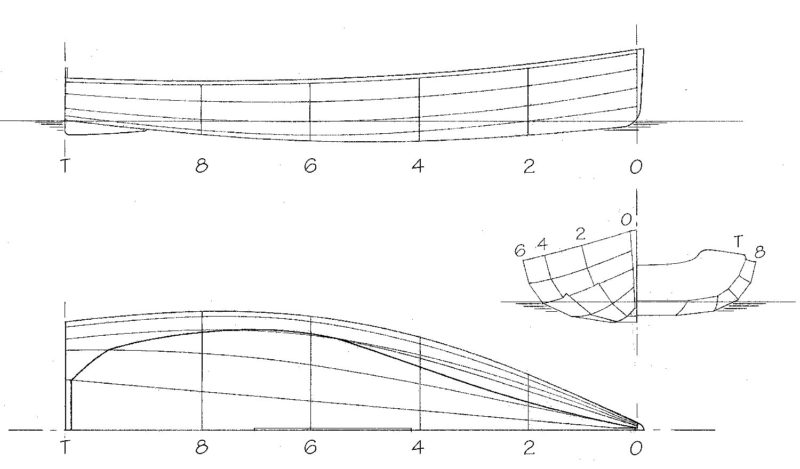

DragonFlyer’s glued-lap hull shows a fine and shapely forefoot. For about the forward one-third of the boat, the lower “lap-edge” of the second plank widens to nearly 1″. This plywood-epoxy edge forms a lifting strake. Brooks reports that the device deflects spray as well as providing hydrodynamic lift. The hull flows gracefully aft through an easy midsection to culminate in a long straight run. Given any reasonable breeze, this shape allows the little sloop to jump up and plane away. The wide “flat” to its bottom and relatively firm bilges, result in good initial stability. Despite its small size, this is not a particularly tender boat.

Designed from the beginning as a kit, DragonFlyer goes together quickly and efficiently with little waste of materials. We’ll build the hull over a framework of interlocking plywood bulkheads and stringers, accurately secured by a series of slots and tabs. This structure gives us a sturdy well-aligned form on which to hang the planks, and all of it stays in the boat. No separate building jig remains to be stowed, tossed, or burned in the shop stove.

Ruth Hill

Ruth HillSealed tanks built under the sole and on either side of the cockpit during construction provide ample positive flotation for this sail trainer.

John and Ruth tell us that we’ll build this hull in standard glued-lapstrake fashion, “with an innovative twist: no laps to bevel.” The kit will arrive at our shop with a constant bevel worked into one edge of each strake. They suggest that we might assemble the frame-work “dry”—that is, without epoxy. This procedure will give us a good practice session free from the deadline pressure of rapidly setting up epoxy.

Then we’ll disassemble the framework. The designers recommend that we proceed slowly and keep careful track of the various pieces: “This is easy to do, so long as you don’t get too far ahead of yourself…especially if several selves are working together.”

When the time arrives for final and permanent assembly, we’ll glue together the frame and apply thickened epoxy to the plank laps. Battens sprung temporarily along the outside of the laps will ease the job and help to ensure that each strake takes a truly fair curve. Those who have built lapstrake hulls in the traditional fashion (cedar planks, bent frames, and no goop) might ask: “How can these strakes mate in a leak-proof manner without nice rolling bevels at the laps?” The answer lies in the strong gap-filling properties of epoxy.

As it turns out, the easy lines of this hull allow the straight-beveled strakes to mate more closely than we might think. John and Ruth originally had planned to plank the prototype’s hull dry and then to inject epoxy into the laps. The surprisingly close fit prevented this. In the end, they proceeded in usual glued-lapstrake fashion: coating the lap joint of each strake before hanging it. This boat’s glued-lap construction consumes relatively little epoxy and requires much less sanding and fairing than the popular stitch-and-glue technique.

Glued-lap hulls have been with us for decades. They are light and strong, and last well. When nicely lined-off, as this hull is, the shadow lines along the laps help define the boat’s sweet shape. But these hulls absolutely demand the use of high-quality plywood and thickened epoxy. If we attempt to build them in this manner with traditional materials, they will split along the laps…perhaps not today, but soon and catastrophically. If we wish to play with solid cedar strakes, we’ll need to re-engineer the structure.

At least for now, DragonFlyer can be had only as a kit or completed boat from Brooks Boats Designs. Building plans might be available in the future. Some of us like to start with a pile of raw lumber, or a stack of virgin plywood, so that we can say, “I built this!” But, if we can get past our builder’s ego, the kit offers advantages. It certainly reduces assembly time, and we know all the pieces will fit properly first time around. Novice builders will find that the kit makes for simpler work and requires fewer tools. Given the kit supplier’s access to materials at lower cost, and the efficiencies of series production for the kit’s components, the monetary savings for building from scratch could prove slight.

There might be yet another advantage to kits. Brooks tells us he has no intention of setting up an organized racing class for DragonFlyer, but he expects that some owners will. If that should happen, having all the boats come from the same source could preclude unpleasantness at hull-measurement time.

John and Ruth and their four children built the first DragonFlyer as a family project. The boat’s distinctive appearance, even from a distance, makes for easy identification. When Ruth sees that bright-red fully battened mainsail far across the busy cove, she knows “those are my kids.” And her kids seem to recognize the bugle call that tells them it’s time to come home.

The DragonFlyer 3.2 has proven fast and exciting under sail. It tacks with certainty and planes readily in any real breeze. The little boat teaches lessons gently yet firmly. Novice sailors soon learn to correct their mistakes, but Brooks and Hill tell us that their children haven’t found this boat to be at all “touchy or scary.” Indeed, kids and agile adults consider the 3.2 to be good fun. Larger skippers might hope that Brooks Boats will offer a DragonFlyer 4.7 (15′ 5″ LOD) somewhere down the road.

Kits for the DragonFlyer, as well as finished boats, are available from Brooks Boats Designs; http://brooksboatsdesigns.com

Brooks Boats

Brooks BoatsParticulars:

LOD 10’8″

LWL 10’7″

Beam 4’6″

Draft, board up 5″

board down 2’9″

Hull weight 100 lbs

Sail area:

Cat 44 sq ft

Sloop 59 sq ft

Large sloop 68 sq ft

Spinnaker 35 sq ft

Brooks Boats

Brooks BoatsDragonFlyer was designed from the start as a glued-plywood kit boat. The kit arrives with pre-beveled strakes, so the hull sections can be assembled dry, before applying any epoxy, ensuring a good fit and no misplaced pieces.

The rig is reminiscent of the Mirror Dinghy.

When I first read this article several years ago, I was very enthusiastic about the Dragonflyer so I searched around for a kit or plans with no luck. I contacted John Brooks and after long wait, I received an email from John explaining that the expense and difficulty of making it into a kit had caused him to decide that the Dragonflyer would be a ‘one-off’ boat with no kits or plans offered.