Jamie Bloomquist

Jamie BloomquistThe Blue Jay–class sloop was designed in 1947 as a junior trainer. Today, the fleet numbers over 7,000, and the boats are sailed by adults and kids alike.

It was blowing like stink, and my perch on the bow of the modern go-fast raceboat was precarious. The spinnaker jibe was not going well. I looked back at Randy, the skipper, who was grinning through the chaos; it was the same grin he had on his face when we capsized my Blue Jay–class sloop nearly 45 years before. I realized then that we’d live through this particular screw-up just like we’d lived through that one. And eventually we’d laugh about it.

If the only thing that Blue Jay taught me those many years ago was to laugh through the small calamities, it would have been enough, but I learned much, much more. Most important, I learned the love of sailing and the love of the Blue Jay class of sailboat. BANZAI, my Blue Jay, has proved to be the boat of a lifetime.

History of the Blue Jay-Class Sloop

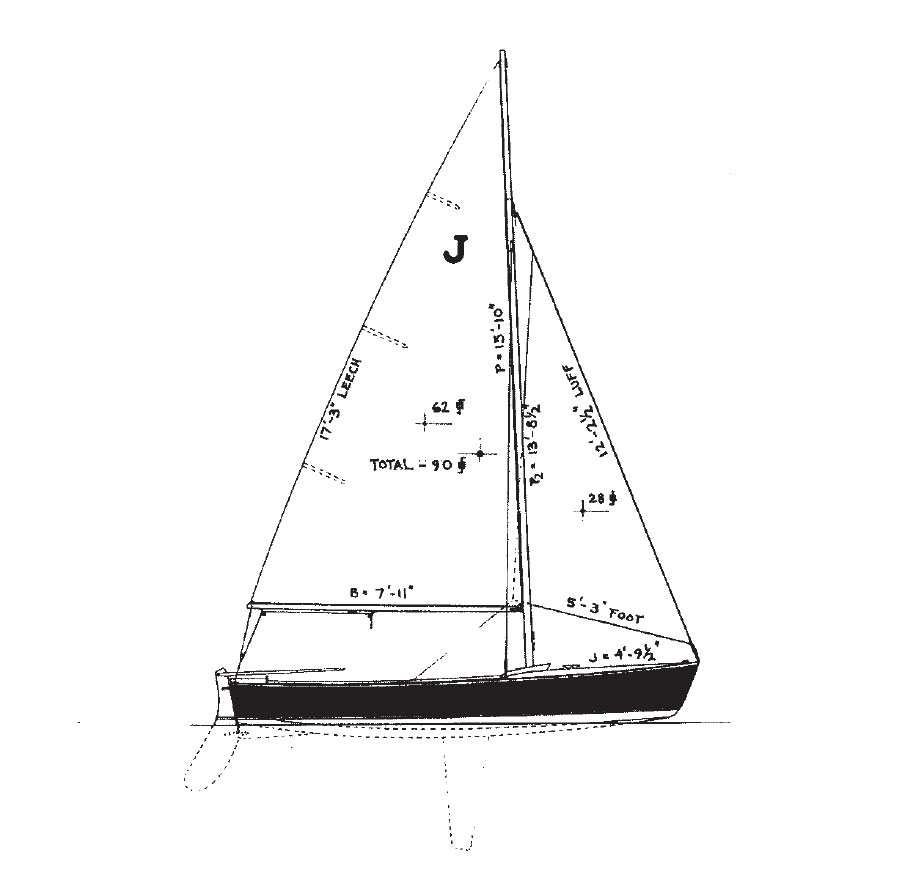

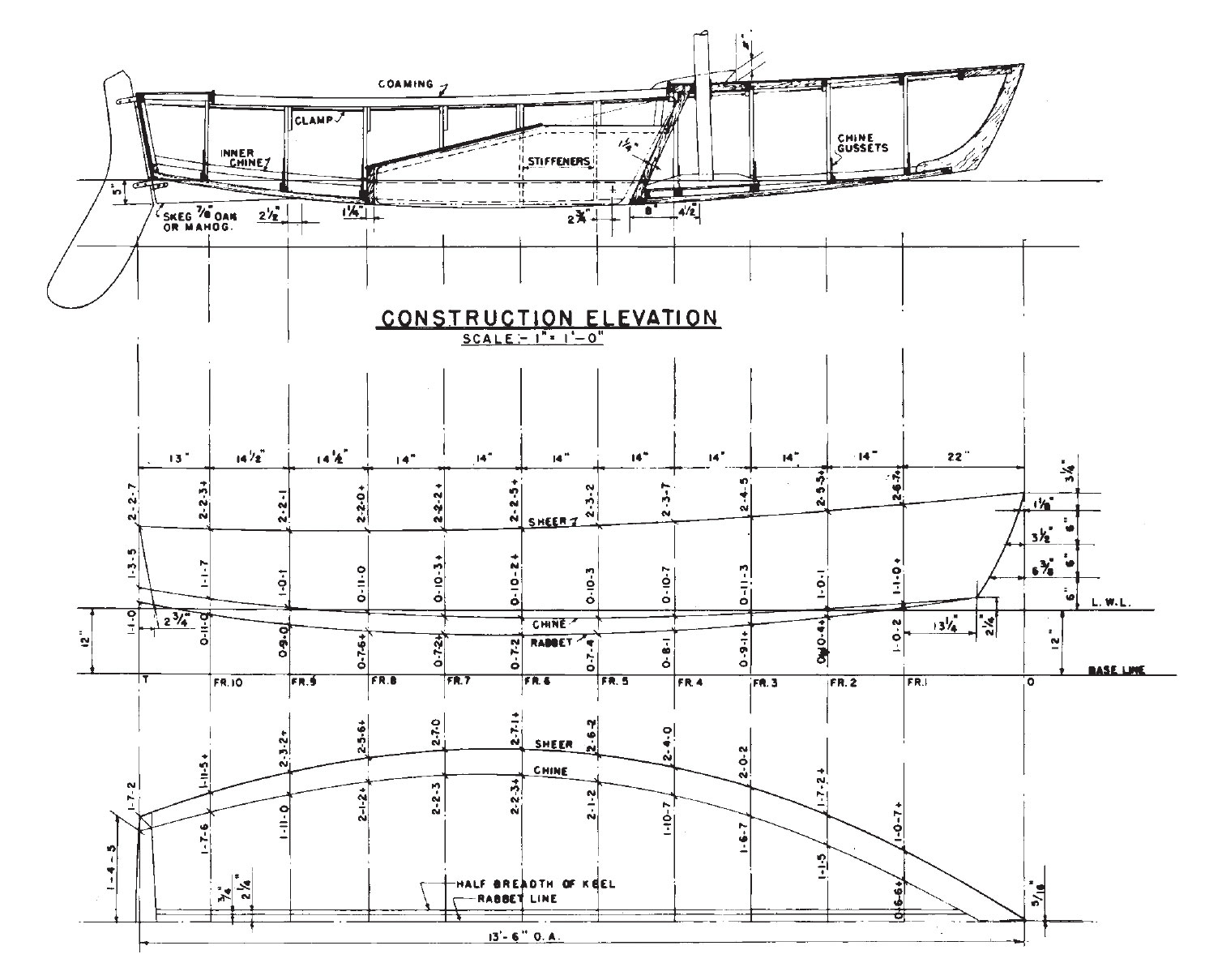

The Blue Jay is a classic little sloop designed by Sparkman & Stephens (S&S) in 1947. It’s a hard-chined daysailer, 13′ 6″ long, 5′ 2″ at the beam, and weighs a minimum of 275 lbs. It carries 90 sq ft of sail in a main, jib, and spinnaker. While its sheer is relatively flat, its bottom is slightly veed and sweeps up nicely toward the stern. It is a very pretty little boat both under sail and at a mooring. While the design is now 60 years old, the Blue Jay’s appearance is still up-to-date.

S&S forged its reputation with fast, deep-draft ocean-crossing yachts, but they designed smaller boats, too. Their Lightning-class sloop is a 19′ centerboarder designed in the days before World War II; it found immediate favor with the growing numbers of middle-class families drawn to sailing, and boats are still being built to this design for active class-racing worldwide. In 1947, S&S designed the Blue Jay as a “baby Lightning”—a junior trainer for the growing hordes of baby-boomer sailors. My twin sister and I were a part of those hordes.

We grew up on the Shrewsbury River, Monmouth County, New Jersey. The Shrewsbury is a shallow river separated from the ocean by a string of sandbar towns. It joins the Navesink River, and the two flow into Sandy Hook Bay just south of New York City. During the mid-1960s, there were fleets of Blue Jays on both rivers, and the annual Junior Sweepstakes Regattas held on the Navesink were drifting matches with dozens upon dozens of Blue Jays, and double the dozens of young teens testing their skills against each other. Lifelong friendships like mine with Randy were formed in regattas like this one.

Ours wasn’t a family of sailors. But we lived on a river, and my parents thought that sailing was something the kids should learn. In 1963, we drove down to Bay Head, New Jersey, to the Hubert Johnson Boat Yard. The unfinished Blue Jay we went to look at that day was the yard’s first, and it looked little compared to the other boats in the shop; a deal was struck, and months later BANZAI was delivered.

The International Blue Jay was built by many small yards like Hubert Johnson, and by many individuals as well. A significant chapter in the early history of the Blue Jay class was community boatbuilding. The boat was designed to be built in plywood over sawn frames and chines. From the late 1940s through the ’60s, yacht clubs, youth groups, camps, and neighborhood families built many boats for their sailing programs. While most of these boats were intended for children, a number were for adults from the beginning.

The Blue Jay is a great junior trainer. It can be raced with two teens, sailed with three or four littler kids, or a parent and a couple kids. It is rigged with a main, jib, and spinnaker and in the right wind and in the right hands, it can really get up and go. The cockpit is big and deep, and long enough for the not-so-tall to stretch out and sleep. While most of my early time in the boat was spent racing or training for racing, some of my favorite memories have BANZAI beached on a sandy island.

While the boat is a thoroughbred one-design with great balance, and is close-winded and quick, it is also fairly forgiving—though as my young friend Randy and I learned on that gusty day 45 years ago, it is not a totally forgiving boat. A moment of inattention left us upside down with the mast stuck in the soft Shrewsbury River mud. After learning that insurance would cover most of the damage, and when the blood returned to my father’s face, we could laugh about our misadventure.

Our family kept the Blue Jay for a few years. In that span of time, I had become totally boat-besotted and under the spell of the great Danish sailor Paul Elvstrom, who had won four consecutive Olympic gold medals in the singlehanded sailing events. I had to have a Finn dinghy like him. The Blue Jay was sold. I went to college and my dreams of representing the U.S.A. at the Olympics drifted away into the haze.

Jamie Bloomquist

Jamie BloomquistDrake Sparkman, one of the founding partners of the venerable design firm Sparkman & Stephens, specified wood construction for the Blue Jay. In the 1960s, the fleet began to allow boats built of fiberglass—though wooden boats are still being built, too.

During the 1970s, the Blue Jay lost its preeminent position as the junior sail trainer to the fiberglass 420. This French design was faster than the Blue Jay, and it had a trapeze. It was modern, it was hip, it was ’glass. The Blue Jay, although now available in fiberglass, seemed like it was beginning to become passé—though many clubs have stayed with the boat because of its good manners and versatility.

Rediscovering the Blue Jay

Many years after we sold BANZAI, my mother found her on the side of the road, looking forlorn and with a hole in the bottom. We got it back for free. I loaded the boat into the back of my beat-up yellow Ford truck and brought it back to Maine, where I was now living. With subsequent renovations BANZAI was able to race again and we finished third in the WOOD Regatta series at the 1992 WoodenBoat Show. Today, we still do some fun races, but most often we daysail—usually with crews of kids and dogs. Sometimes I sail gloriously alone.

I’m not alone in my experience: many adults who were brought up in the Blue Jay are being attracted back to the boat. On the class’s website are requests from people across the country trying to find the boats they used to own, or ones of the same vintage.

The big cockpit that swallowed up all those little kids is just right for a couple of getting-larger middle-aged folk to have a comfortable day sail. I find it still has the same sprightly performance I recall from childhood, although the tiller seems to be a lot lower today. Adult newcomers enjoy the boat, too.

John Hanson

John HansonMany sailors who were raised in the Blue Jay class are today trying to relocate their childhood boats. Sam Hanson, seen here, is lucky: His dad found his old boat, inspiring a new generation of Blue Jay aficionados in the Hanson family.

The Blue Jay has a few faults. The plywood construction of the past did not have the benefits of modern epoxies, and the decade-old plywood panels can get a little beat. It is hard to fix the centerboard trunk leaks brought on by old age. If you are looking at older boats, look for signs of delamination and ask a professional to check the boat over. Don’t let a little damage kill a good deal, though: a lot of age-related deficiency can be repaired with a little skill, money, or both.

On the water some of the boat’s benefits are drawbacks as well. The big, beautiful deep cockpit is not self-bailing, which means rainwater can be a pain, and with the narrow side decks and no flotation, the boats can capsize. While they will not sink completely, older Blue Jays cannot be sailed out of a capsize as can, say, a Laser or a 420. The up-side is that this does teach caution.

These flaws are minor compared to the joys of owning and sailing a classic yacht from the boards of one of the world’s most prestigious yacht design firms. Today on the classic-yacht-racing circuits of Europe, sailing a Sparkman & Stephens boat is ne plus ultra. You can’t get much better. Olin Stephens, the firm’s cofounder, died at age 100 in September. With an International Blue Jay, you too can be pretty swank, sailing your own Sparkman & Stephens classic. And you can laugh about it.

For design information, contact Sparkman & Stephens, 529 Fifth Ave., 14th Floor, New York, NY 10017; 212–661–1240.

For Blue Jay Class Association news and information, visit the Niantic Bay Sailing Academy Blue Jay Class Association pages.

Blue Jay-Class Sloop Particulars

LOA 13′ 6″

Beam 5′ 2″

Sail area 90 sq ft

Draft (board down) 4′ 0″

Draft (board up) 6″

Weight (with motor) 275 lbs

The Blue Jay’s lineage should be apparent to those who know classic one-designs.

The boat is a “baby Lightning”—a diminutive version of one of the world’s most popular classes.

The Blue Jay is a wonderful class. I enjoyed the article very much