With a sleeping bag in place, the bunk is ready for the night.

Cruising under sail and oars can be an odd combination of casual relaxation and nonstop intensity. It means uninterrupted time on the water, to be sure—and intimacy with nature and the elements. But the imperative of covering miles to make it to the next safe anchorage, or home, can sometimes involve a relentless focus that can be mentally exhausting. Getting a good night’s sleep is imperative.

Sleeping well on board starts with choosing an anchorage wisely, setting a heavy anchor on an appropriate rode, and getting settled early enough to eat well, get organized, and enjoy the evening light. In addition, having a comfortable place to bed down makes all the difference in facing the next day, especially in less-than-sterling weather. I had been sleeping on the floorboards of my 18′ No Mans Land boat, which worked well enough. But my feet were captive under the after thwart, and the space between the centerboard trunk and the side seats was, admittedly, a bit tight. Plus, the floorboards could be damp, or downright wet, from the day’s rain or spray.

It all seemed acceptable enough, though, and I didn’t give my sleeping arrangements much more thought—at least not until I happened to be in Portsmouth, England, during a voyage and went to see HMS VICTORY. There, in the admiral’s cabin, was a sort of plank-bottomed, canvas-sided box slung from the beams overhead. Though not original, this reproduction of Horatio Nelson’s hammock, down to the froufrou embroidery done by his mistress, seemed more than a bit “precious” to me. Nevertheless, the idea was interesting enough to remember.

It came back to me on a solo cruise, during a driving night rain. I had jury-rigged a tent out of my mainsail—a bad idea, since the Tom Sawyer approach is often lacking, and cheating nature is a losing proposition. As soon as the reefpoints started dripping rather liberally, I threw my gear on top of the oars on the other side, which was drier because the sail was doubled there. I perched my sleeping bag on top of it all—and I distinctly recall muttering, among other expressions, that this just wasn’t any fun. Right then, I vowed to come up with a better tent, which I’ve done. In that moment, I had time to think more about Nelson’s hammock. I also fondly remembered the security and comfort provided aboard racing yachts by lee cloths, those simple canvas panels held vertical by lines to overhead deckbeams to prevent off-watch sailors from being thrown from their berths during a change of tack. When I got back home, I made the simple canvas bunk that I designed in my head that night.

photographs by the author

photographs by the authorFloorboards provide a reasonably good sleeping surface, but a purpose-made boat bunk is more comfortable. Here, the mainsail is rolled around its yard and slung between the main and mizzen masts. With thole pins removed, a tent pole set in the vacant holes arches from one side to the other to provide a generous interior space. The tent cover is omitted here for clarity.

This bunk, designed around a standard camping pad, is made of readily available synthetic canvas. The bottom has five 1-1/8″ x 5/8″ wooden slats slipped into sleeves. I made the sides about 6″ high. The ends are generously peaked, each supported by an additional 3/4″ x 3/8″ slat. The whole thing rolls out on top of two oars, laid on top of the thwarts. (Aware that this “traps” the oars, I always keep a good-sized paddle forward in case I need to maneuver at night.) Lines from grommets in the end panels and sides extend up to the spar-and-sail bundle that I sling between the masts to serve as a ridgepole for my tent.

The first attempt didn’t work well. I made the slats a bit too thick, thinking they would need to withstand point loading. But with the standard foam pad slipped into the bunk, I couldn’t get my hip and shoulder to find comfortable spots between the slats. I considered adding more slats to spread the load, maybe making them thinner to avoid too much bulk to stow. But at an outdoor store I found an insulated air sleeping pad that has a built-in pump operated by hand pressure to blow it up to about 3″ thick—much thicker than my earlier-generation one. This was perfectly comfortable, plus the air pad packs in less than half of the volume of my old foam pad, and less volume in stowage is always a real benefit aboard a small boat.

Modified foam pads—the type used for cartopping canoes and kayaks—protect the thwarts from the oar looms forward.

The oars are lashed at both looms and blades to keep them and the foam pads in place.

The canvas bunk rolls out over the oars. All lines remain with the bundle to hasten setup.

The bottom of the bunk is turned up here to show the line about to be unknotted and then tied around the oar below.

The short line extending from the bottom of the bunk, now tied around the loom, keeps the bunk in place over the oars.

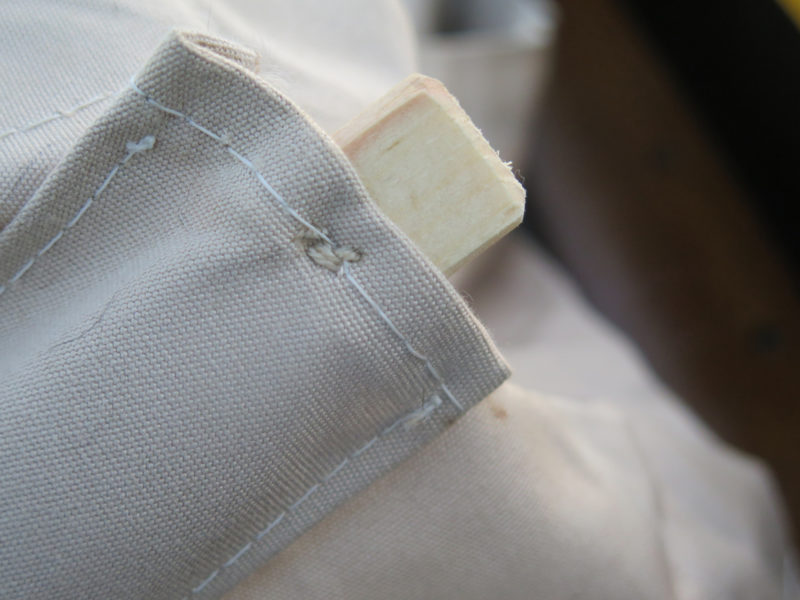

The 1-1/8” x 5/8” bottom slats, made of common pine, are fitted into canvas sleeves. At each end of a slat, the canvas layers are sewn together with sailmaker’s twine through a hole bored in the wood, keeping the slat from sliding out.

Lines pass over the main yard and are made off to keep the bunk’s sides and ends vertical. Note the short lines passed through grommets inside the bunk—they tie the slats to the oars.

The canvas “box” was designed around a standard-sized camping pad, which is inserted next. Note the 3/4” x 3/8” slats sewn into each end panel to keep them from collapsing.

The bunk, with all of its associated gear, fits into a large dry bag along with my tent and mosquito netting, and takes just a few minutes to set up. There’s ample room underneath to stow things I won’t need for the night, keeping them from getting underfoot. I am the admiral of nothing and have no embroidering mistress, but with the boat well anchored down and a good book at hand, I can look forward to a fine night’s rest and to arising refreshed at the next day’s dawn, ready for more sailing and whatever the day might bring.![]()

Tom Jackson is the senior editor of WoodenBoat.

You can find a picture of Nelson’s bed on the HMS VICTORY web site at the bottom of the page.

If you’d like to share your tricks of the trade with other Small Boats Monthly readers, send us an email.

I would like to see an article about your boat. It seems like you put a lot of thought into it, and made modifications by trial and error.

Thanks for the post. I’ve written about the boat several times, most notably in WoodenBoat No. 235 (“Wood in the Rigging: Making simple fittings for a traditional boat”) and No. 202 (“A Suit of Sails: With no original sail plan, all the options are open”), as well as WoodenBoat‘s Small Boats print edition of 2012 (“The No Mans Land Boat: A challenge with great potential”).

The Small Boats article is generally about the type, plans available for various examples, and my experience of interpreting one of them. The sail article worked on developing eight different viable rigs, and the wooden fittings had to do with thimbles, toggles, blocks, parrel beads, and the like.

What Bob says, Tom. Wow, for some reason I was thinking lengthwise slats. Stowage is easier with the athwartship layout, however being an older guy, I would for sure need a good mattress. I like it. If Nelson slept in one then it’s got to be pretty good.

Is that the No Mans design Robert Baker took lines from? We have a North Shore Dinghy built by Eric Hvalsoe and his class at CWB in Seattle. You should show us your boat, maybe even Maynard’s Coquina. That’s a hoot that Kirby’s is selling a paint color named after him. I guess he is officially an Old Salt now.

Thanks for another great issue.

My boat is the Beetle design, recorded in Plate 63 of H.I. Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft. I think it’s the best of the type.

Your opening paragraph Tom, is spot-on. I’d never yet heard it phrased so accurately as you have. As you stated, you’re trying to enjoy yourself, but, to a very great extent, can’t because you know if you don’t make it to the Plan A anchorage you’ve set out for (and don’t have a decent Plan B) it’s going to be a bad night. “Nonstop intensity” and “relentless focus” capture the nature of the dilemma most eloquently. The primary cause of the dilemma, in my opinion, is that you’ve chosen to go out there without a motor. For people with motors (as you look at them enviously pass you by blissfully en route to their Plan-A anchorage), when things go awry, they just lower sails and hit “Direct” on the GPS. For those without motors, having things go awry (too much wind, not enough wind, no wind at all, rough seas, wind coming directly from where Plan A anchorage lies, and aching arms from too much rowing) changes everything. And it’s not enough that you make it to the anchorage before dark. If you plan on having any time at all to sit back and enjoy dinner, you’ve got to get to the Plan A anchorage a good hour and a half before dark, You’ll need 15 minutes to set the anchor, another 15 minutes to nap (to collect your wits and rest your weary bones), and an hour for dinner, cleaning up, and putting boat and self to bed for the night. And many nights, Plan A anchorage just isn’t going to work, once you get there, for any number of reasons, so off you go off to Plan B anchorage, watching the sunset and often going without dinner. Too bad, get over it, you tell yourself, at Plan B anchorage, as you fall asleep thinking about the wonders of food, promising yourself to pick a better Plan A anchorage tomorrow.

Thanks for the observations, Brad. Sailing without an auxiliary is a challenge, but I would argue that the challenge itself is a big part of the enjoyment! It is for me, anyway.

Nice article. As a big Patrick O’Brian fan I was aware of those sleeping “boxes” for a while and always thought they might be an interesting option for space-tight small boats and preferable to standard bunks. I have one of the ultralight “jungle hammocks” that might have an advantage on a small open boat of providing better protection from rain in an open boat (most of them incorporate some sort of pad as well). Maybe use the oars as “trees” at each end of the boat to hang the hammock!

Stringing your hammock up in a small boat might work if you really like being rocked to sleep. I’ve spent a lot of time sleeping in hammocks—the “jungle” kind with mosquito netting and a rain fly—and always try to get in without setting the hammock swinging. I find the motion annoying enough when the hammock’s over solid ground. And don’t like trying to sleep in in a rocking boat. For me, being in a hammock in a small boat at anchor would be a waking nightmare. Hammocks work in large vessels like HMS VICTORY because they roll slowly. I’d suggest stringing the hammock up high enough to support netting and fly, and low enough to allow a fixed platform support your weight.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor, Small Boats Monthly

I think a slung hammock in almost any small boat would be a bad choice, and potentially a dangerous one. The center of gravity is too high in the first place, plus when the hammock swings, your center of gravity swings with it. Any roll would put your weight too far outboard, and the higher up the mast the hammock is anchored, the worse that problem would get, especially in a narrow boat. Also—I guess people have different preferences, but for me the few nights I’ve spent in a hanging hammock (on land) were the most miserable I’ve ever spent.