Here’s a flat-bottomed sharpie ketch that we can build in the backyard. This shoal-draft boat will sail on the morning dew, right itself after a knockdown, and leave most deep-keel cruisers in its wake.

Photo by NIS Boats

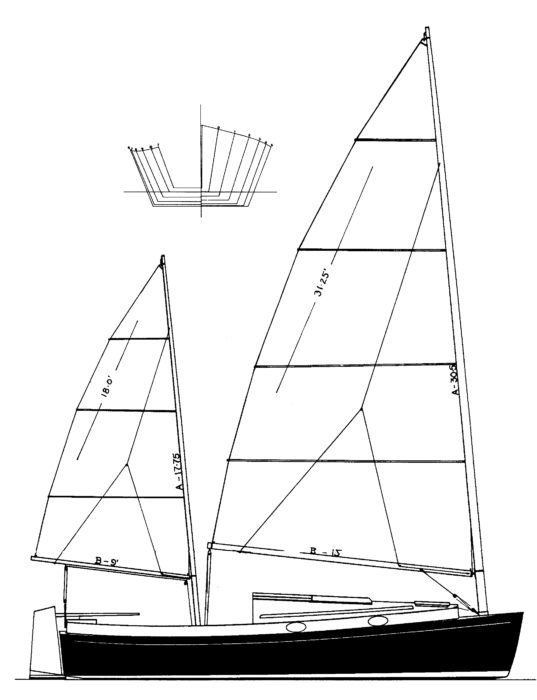

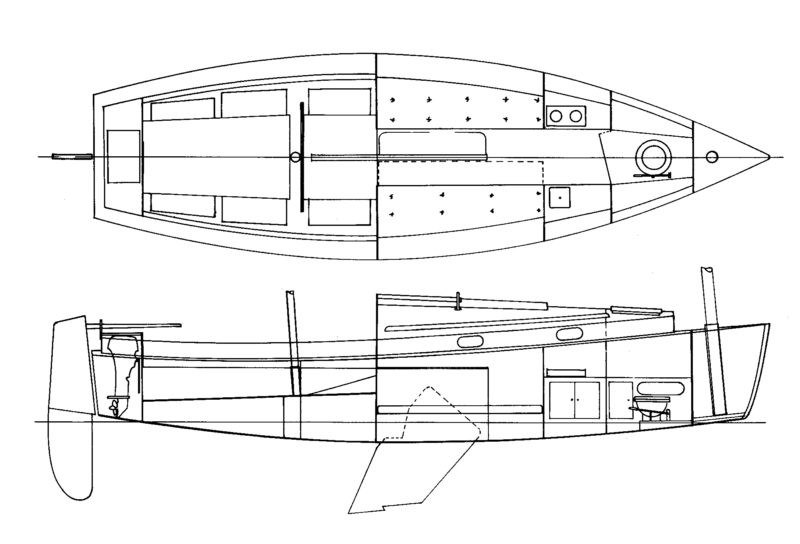

Photo by NIS BoatsThe sheet-plywood Norwalk Islands Sharpie (above and opposite) can easily be built in the backyard, yet it outperforms more expensive yachts. Its simple cat-ketch rig needs no standing rigging (wire shrouds and stays that support the masts). The outboard-motor lifts into its own house when idle—no ugly mounting bracket, no hydrodynamic drag.

More than two decades back down the road, I visited with designer Bruce Kirby at his Rowayton, Connecticut, office. A crackerjack sailor, he was best known for his design work for the Canadian AMERICA’s Cup challenger and for having created the Laser, a sophisticated 14′ singlehander that revolutionized sailboat marketing in the 1970s.

I found the talented designer of high-tech sailboats hunched over the drawings for a simple sharpie that was to become the Norwalk Islands 26. He was excited about the design—with, history now suggests, ample justification. The easily built ketch sails fast on all points, offers reasonable cruising accommodations, and can handle rough water.

Photo by NIS Boats

Photo by NIS BoatsSailing wing-’n-wing off the wind—no need for a spinnaker here.

Kirby drew a handy cat-ketch rig to power the NIS 26—no labor-intensive overlapping headsails or tiny, impotent mainsails here. Full-length battens support considerable roach, that is, curve to the leech (trailing edge) of each sail. This allows more sail to be carried on spars of a given length, and it provides a more efficient sail shape. As an additional benefit, these sails are quiet. They don’t flog wildly when luffing. But we need to pay attention, as fully battened sails won’t telegraph word of improper trim in the immediate manner of unsupported sailcloth.

This is a controllable rig. We can fuss with the tension and taper of the battens to alter sail shape. We can back the mizzen to stop the boat or put it into a slip. A word of caution: unless we actively control fully battened sails, they tend to keep sailing. Simply releasing the sheets won’t quickly stop the boat. We should remember this as we approach the dock, lest we come to rest in the parking lot.

The original NIS 26 rig measured 302 sq ft. After sailing the prototype, the designer increased the area to 340 sq ft. He also has changed from aluminum masts to sticks made from carbon fiber. The greater heeling effect of the larger sails seems to be offset by the lighter weight and greater flexibility in the upper portions of the tapered, thin-wall masts. In strong winds the masts bend, thus relieving tension on the upper leeches.

Photo by NIS Boats

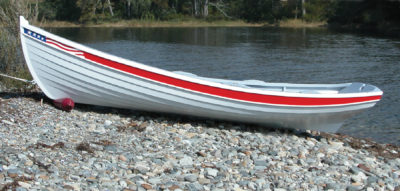

Photo by NIS BoatsWith a draft of only 10″, the Norwalk Islands 26 can sail through marshes.

Robert Ayliffe, who sails and sells Norwalk Islands Sharpies from his base in Australia, recently devised a nifty tabernacle that makes raising and lowering the sharpie’s masts a casual singlehanded operation. The boats now will get underway quickly from their trailers, and we’ll have ready access to bridge-blocked water. Given a 10″-deep stream no wider than your driveway, we can sneak our NIS 26 into it…to hide from a hurricane or simply to get away from the crowd. Plans for the NIS 26 describe both a two-berth interior and a “sleeps-four” production-boat layout that carries a double V-berth forward and two quarter berths in the main cabin. The centerboard trunk is tall, which allows it to house the required board. (A sharpie will not go well to windward without a centerboard of substantial area.) Much of this trunk resides innocuously below the sole of the self-bailing cockpit. The aftermost berths in both accommodation plans offer sumptuous seating in the main cabin, and we’ll make good use of the exposed portion of the trunk by hanging a dropleaf table from it.

Both plans show “enclosed” heads, but you should understand that we won’t find anything resembling true privacy aboard a 26′ sailboat.

Photo by NIS Boats

Photo by NIS BoatsBring the boat right up to almost any shore.

The outboard motor, which provides auxiliary power, resides out of sight in its own house way aft. When not in use, the engine lifts vertically. We’ll not need to worry about dragging the propeller around the bay while we’re sailing, and we’ll have fewer concerns about corrosion of expensive machinery when we’re at the mooring.

All of this seems fine…but how, you might ask, can a sailboat that has no deep keel and that floats in only 10″ of water right itself? Here are some design rules to follow if you want a shoal-draft sharpie to pop up reliably from knockdowns and inversions: Draw the combined hull-house structure rather tall (say, at least 4′ for a 26′ boat). Keep the width on deck to an acceptable minimum so that the boat won’t become stable in an upside-down position. For the same reason, a strongly crowned housetop and/or deck will help (acting as a “round bottom” when the boat is inverted and providing plenty of volume where it’s needed). Concentrate structural weight low— make the bottom brutally heavy, as it will provide secure ballast as well as protection during hard groundings. To keep the center of gravity low, spread well-secured inside ballast in the bilge (do not pile it up against the centerboard trunk). Build the cockpit small, and be certain that it is self-bailing. Locate hatches near, or on, the boat’s centerline. Make the rig low and light. Last, be certain that everything is strong and tight. Yes, extremely shoaldraft boats really can right themselves without violating any laws of physics.

Photo by NIS Boats

Photo by NIS BoatsThe brilliant performance of EXIT 12, designer Bruce Kirby’s prototype NIS 26 (right), surprised Long Island Sound sailors during the 1980s.

Not all sailors will like the appearance of a boat designed to the above parameters, but Kirby has a good eye. On the NIS 26, a strong sheerline and dark hull sides lessen the visual impact of substantial freeboard. Low house sides and extreme crown (athwartships curvature) to its top reduce the apparent height of the house. In all, this ketch has a seamanlike look about it.

So, there you have it, a fast and easy-to-build cruiser that will take us to shallow coves that lie just out back of nowhere.

Bruce Kirby’s drawings reflect the startling simplicity of the NIS 26, but this flat-bottomed sharpie has been well proven in tough conditions around the globe.

Plans for the Norwalk Islands Sharpie are available from the NIS Boats. .

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I have a friend who built one early on and he enjoyed the boat for several years until moving forced sale of the boat. I’m forwarding this email to him as I suspect he still has fond memories of his NIS. Is there any more information available as he is now suffering from Parkinson’s?

Thanks,

Paul

Hi Paul, I’m one of the moderators for a Norwalk Islands Sharpies group on Facebook. Members of the group are mainly builders and owners of these wonderful craft plus a number of people who are just keen admirers. You and your friend would be most welcome to join. I also have quite a lot of information, photos, etc. as well as details of who owns which boats. Feel free to email me at [email protected] if you have any queries.

Cheers,

Pete

I had one (26) and my only comment is have a sail on one before you commit.

They are not as straightforward as some other boats. Bruce Kirby’s name is always mentioned but anyone who has raced a Laser will understand what it is like to hit the bottom mark in a strong wind. They are tippy. So are the NIS. They bob around and caper at times. You need to be well ahead of them in a bit of wind mentally. Not as simple as a sloop-rigged yawl for instance. Just saying. They are also a big boat. You need to be pretty athletic at times. I was younger then too. I think the B and B yachts equivalent with a bit of chine would be something to look at. Will probably get shouted at here but that was my experience.

Looking backward at the experience I reckon the 23 would be a better experience.

I am not trying to stir up trouble, just reporting.

Rob

Hi Rob,

I appreciate your comments as a former NIS 26 owner (remember you were previously a member of the NIS Yahoo group?), but I’d suggest the Laser – NIS comparison is not relevant.

Similarities between the laser dinghy and the NIS – freestanding rig, quick and simple to rig, shallow draft with centreboard, designer.

Differences between the laser dinghy and the NIS:

Laser

– is a cartoppable high performance dinghy weighing around 60kg with rounded chine, designed for racing and has no ballast, relies on crew actively hiking to keep it upright, can capsize relatively easily and needs to be righted by having the crew stand on the centreboard. Crew sits “on” the boat more than in it due to small footwell, so no protection from wind and waves. Cannot self-steer due to lack of balance of rig.

NIS

– is a trailerable (in case of 18′-29′ versions) yacht with hard chines, very robust, weighing around 8-900kg in the case of the 18′, and maybe 2000kg in the case of the 26′, designed primarily for cruising, has at least 250-300kg (18′) and perhaps 600kg (in case of the 26′) of ballast attached to the bottom and a barely ballasted centreboard. So NISs are definitely not rock solid like a yacht with a fixed keel, and particularly in the smaller sized 18 and 23, the crew-weight is a higher proportion of the boat’s total weight, so does have an impact on balance, but in the unlikely event that they ever capsize they are nevertheless entirely self-righting (Kirby arranged some testing which gave a theoretical self-righting from over 100deg). The NIS is initially “tippy” likely due to its relatively narrow waterline beam, but thereafter is very solid and resists further heeling due to the ballast and to the flared topsides. The NISs are incredibly dry boats to sail, with high freeboard, protective coaming around the cockpit, high crowned cabin top, plus a self-draining cockpit. Also, when well set up with controls all lead to the cockpit, there is rarely a need for the crew to move forward. I agree that sailing the NIS with the freestanding cat ketch rig is definitely different from sailing a traditionally stayed-rig sloop, but I would suggest that what is different is that they are so easy and foolproof to sail, with only two sheets – mizzen and main – to worry about, rather than having to tack a foresail, and they are often so well-balanced with the wind ahead of the beam that they steer themselves. So perhaps they are not “straightforward” in the sense that someone used to sailing a traditionally rigged boat might take a short time to get used to it. One NIS 26 owner had a wonderful analogy – saying that his NIS was like sailing an “automatic” – meaning there was little that the crew has to do.

My comments are based on over 10 years of familiarity with the NIS, including talking with many owners over those years, and having sailed on six NIS 18s, six NIS 23s, two NIS 26s, and one NIS 29, including in coastal sailing in Bass Strait. At no time did I feel unsafe sailing any of these boats.

I thank you for featuring my Boat in your article on NIS 26, the green one RO140S. I did not have the pleasure of building Little Jimmy, I have owned the boat now for seven year in that time I have renamed and repainted in black.

THE PEARL is the new name it’s a great boat for me because I am a novice to sailing and I can single hand sail her with no problem. As you see you they are a great vessel for shallow waters can pull up on any beach and just step off. I find The Norwalk Island Sharpie’s are an eye-catching craft and mine turns head where ever I sail and comes with onlookers, asking a lot of questions. Due to the COVID-19 restriction I haven’t been able to sail for a while. I’ll try and get the boat in the next Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart Tasmania.

The top picture was taken at Matilda Bay Perth Western Australia.

Kind Regards,

Colin Wright

Hi Colin – I’m thinking about buying one of these boats. How have you found it’s stability in the open ocean? How would it handle coastal sailing on the Aus East Coast for example?

They go pretty well according to Robert Ayliffe! He sailed his 23 across the Bass Strait.