In American Small Sailing Craft, author Howard I. Chapelle writes: “Perhaps the most noted of American rowing work boats was the Whitehall.” That was the case in New York City, beginning in the 1820s, when Whitehalls served as water taxis. Two hundred years later, the Whitehall, in its many forms, may be the most noted American recreational boat.

Christopher Cunningham

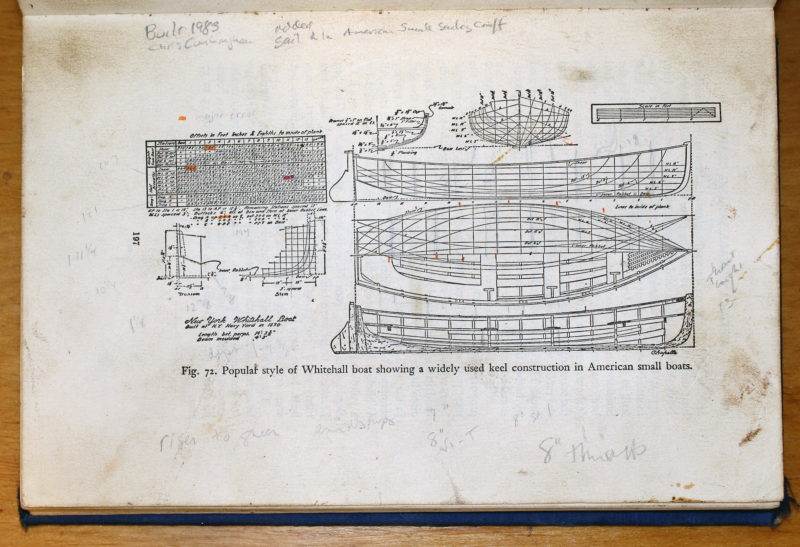

Christopher CunninghamThese drawings and offsets in American Small Sailing Craft provide just enough information for an experienced boatbuilder to build the New York Whitehall. The orange highlights are errors I found; they were easily identified and worked around.

Chapelle’s drawings of the New York Whitehall built in the New York Navy Yard in 1890 occupy a single page in his book and include both lines and construction in profile, section, and plan view. The offsets and text suffered in the reproduction of the original artwork and require a magnifying glass to read. The two pages of text preceding the illustration delve into the history of the Whitehall type and offer general comments on the New York model’s construction: plank keels, skegs, steam-bent frames, white cedar planking, and oak keel and posts. Even for an experienced boatbuilder it’s a bare minimum to go on, and additional resources, particularly John Gardner’s chapters on Whitehalls in Building Classic Small Craft, are helpful.

As I was lofting the hull, I discovered four errors in the offsets. They were obvious enough—I would have to torture the batten to touch the marks for them—that they were easily identified and ignored. I made 13 molds, one for each station in the table of offsets, and set them at 12″ intervals on a ladder building frame.

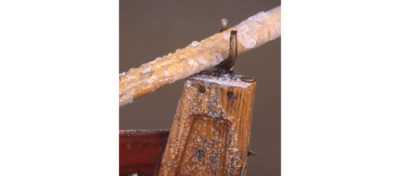

Chapelle notes two ways of constructing the plank keel: “The most common way was to make the plank keel straight with the skeg erected on it. A less common method was to spring the plank keel so that it followed the rabbet aft and then apply the skeg below it. This made a very good construction, but there was sometimes great difficulty in bending the plank keel and holding it in place while building.” I chose the latter and steamed the aft ends of the plank keel and its hog to curve them around the molds. It was indeed hard to make the bend and hold the keel pieces in place. The keel’s ends are secured to an oak stem and its knee forward, and the heart-shaped mahogany transom and its knee aft.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe carvel-planked boat documented by Chapelle was built in 1890, and was typical of the Whitehalls built between 1860 and 1895. Prior to that, from the beginning of the type in the late 1820s, Whitehalls were lapstrake.

The first Whitehalls were lapstrake, but by 1850 most were carvel planked. I opted for the original construction, believing that lapstrake is better suited for a trailered traditionally built boat that spends most of its time out of the water. Instead of the 3⁄8″ white cedar Chapelle cites, I used 7⁄16″ Port Orford cedar for the planking and, like the original Whitehalls, mahogany for the sheerstrake.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamAlmost 130 years after the original New York Whitehall was built, the hull form remains popular among rowers.

Planking, whether carvel or lapstrake, begins with lining off the hull to determine the plank sizes and shapes. This step takes time to do properly so the planks’ widths in the finished boat are uniform and their curves are fair. I lined the hull off for 10 strakes instead of the nine indicated in the drawings for carvel planking. The first several strakes have a considerable twist in them and require steaming to get them to relax before being fastened to the stem and transom. The original carvel hull had 3⁄8″ x 1″ steam-bent frames on 12″ centers. For my lapstrake hull, I used frames with the same scantlings on 6″ centers.

The 1890 Whitehall had thwart knees made of ¼″ x 1″ metal straps—probably bronze—with T-shaped ends secured to the thwarts. I had a collection of fruitwood crooks and used them instead. In the bow, level with the forward thwart, is a wooden grate with a chevron design. It is tricky to build, but pretty enough to be worth the effort. I added cleats on the bottom side to provide support to all the half-lapped crosspieces.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe rudder is equipped with a yoke and is designed to be operated by a passenger. The backrest, while not indicated in the plans, keeps the passenger’s weight from being planted in the stern where the hull is cantilevered over the water.

In the sternsheets I added a backrest similar to one in Gardner’s chapter on Whitehalls. It simply drops in place and keeps a passenger’s weight from settling well aft, right up against the transom, which is a bad place for boat trim. The drawings indicate a yoke instead of a tiller, the best option because a passenger can sit centered in the sternsheets and face forward to steer. The rudder’s bottom is even with the skeg so the boat can be beached without having to tend to a rudder with a deep or drop-down blade.

The grating in the bow is a distinctive touch. I’d initially screwed it to the risers and a support extending from the underside of the thwart. To get better access to the bow, I later made it removable with a small thumb cleat on the stem and two turn buttons on the forward ends of the forward thwart.

The floorboards follow the run of the plank keel perimeter and the laps of the first two strakes, and are screwed to the oak frames. I have a hole in the center floorboard for a bilge pump, but otherwise don’t have access to the space beneath the floorboards. Eric Hvalsoe’s system for removable floorboards would improve access for maintenance (and retrieving stray pencils). Because the hull curves up on top of the skeg, the best place for the drain plug is in the plank keel at the bow just aft of the stem.

Lily Cunningham

Lily CunninghamWhitehalls are well known for their shapely wineglass transoms. Chapelle referred to them as “heart-shaped.”

The New York Whitehall is shown without stretchers for rowing. Gardner’s 17′ Whitehall has two pairs of stretcher cleats fastened to the floorboards for use with a removable stretcher, but in my Whitehall they would pose a tripping hazard so I devised one stretcher that is supported underneath the sternsheets and another hung from the aft thwart.

The New York Whitehall’s 7″-wide plank keel has an advantage over the more common vertical keels: at the ramp the boat behaves itself on and off the trailer and sits upright on the beach. With its round bottom and a beam of 4′3″, the Whitehall feels only a little unsteady when I’m getting aboard, but once I’m seated it’s comfortably stable.

The three sets of oarlocks have spans of 41-1⁄4″, 50-1⁄4″, and 49-1⁄2″ (bow to stern), calling for oar lengths of 6′8″, 8′1″, and 7′11-1⁄2″ (calculated using the standard formula). I made oars at 6′10″, 7′4″, and 8′. I rarely use the 8′ oars, and I’ve recently been using a pair of 7′6″ oars at the center station and like the way that length feels.

Rachel Hynd

Rachel HyndThe 14′ Whitehall is a good size for a solo rower and makes satisfying speed both on calm water and when the wind kicks up a chop.

I row solo on the middle of the three thwarts that serve as rowing stations. The skeg provides good tracking and doesn’t require constant attention to hold a course. It takes 11 strokes—pulling with one oar, backing with the other—to make a U-turn. Rowing solo I can maintain 3.5 knots knots with a relaxed effort, hold 4.3 knots at an aerobic fast pace, and hit 4.9 knots in a short sprint. With my son rowing with me, the Whitehall did 3.8, 4.3, and 4.8 knots respectively. When I rowed in the forward station with him as a passenger in the stern, the speeds were 2.8 , 3.5, and 4.1 knots

Lily Cunningham

Lily CunninghamThe spacing of the rowing stations amply separates two rowers, thus minimizing the clash of oar blades should they get a bit out of sync.

With two aboard, both can row by occupying the forward and aft stations—the 57″ space between them provides plenty of room. The Whitehall trims down by the bow a bit in this configuration, particularly when finishing the stroke with a strong layback. With two at the oars and a passenger in the stern, the Whitehall trims well and the rowers can pull hard and leave the steering to the “coxswain.” To aid steering for rowing double without a passenger, I made a stretcher with a foot-operated tiller that gets connected to the rudder-yoke lines.

Nate Cunningham

Nate CunninghamA single rower in the forward station with a passenger in the stern trims the Whitehall just right.

Chapelle notes, “The boat was not for use in the open sea, but was designed for large bays and harbor work, where a heavy chop might be. It rowed fast in smooth or choppy water; it was safe, carried a heavy load easily, and was dry.” I’ve confirmed that by rowing my Whitehall in winds up to 24 knots and waves beginning to crest. It carried its speed very well, even upwind, and wasn’t hampered by plowing through waves.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe 1890 New York Whitehall did not include a sail rig, but the plank keel makes it easy to add a mast step and centerboard trunk.

The drawings for the New York Whitehall do not include a sail rig but, according to Chapelle, “boats which covered great distances, such as ship-chandlers’ boats, often were fitted to sail, and had a small centerboard and a low spritsail.” Gardner’s drawing of a 14′ sailing Whitehall with a hull similar to the New York model shows a sprit main with a small jib and a rectangular centerboard trunk. The oak plank keel makes the addition of the trunk and the maststep easy by providing a flat surface to mount them without having to involve modifications to the garboards. For sailing, I swap the rudder yoke for either a standard tiller or Norwegian tiller for better control with one hand. The Whitehall performs well under sail, but I’m not as agile as I used to be and find it awkward to move about in the small cockpit while coming about or responding to gusts.

The New York Whitehall is not an easy boat to build, but it is an excellent exercise in traditional construction. While many contemporary boats endeavor to duplicate the Whitehall shape in modern materials, one built as the originals were in the middle of the 19th century can be a great pleasure to row and is always gratifying to look at. Mine is now 39 years old and with its traditional construction should serve a few more generations to come.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

New York Whitehall Particulars

Length/14′ 3-3⁄8″

Beam/4′ 3″

Depth amidships/16-3⁄8″

The drawings of the New York Whitehall are in Howard I. Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft, published by W.W. Norton & Company.

I second the idea that these traditionally built Whitehalls (and close variants like our Tyee salmon wherry designed in the 1920s up in Campbell River BC) are keepers. These are boats that somehow feel they will take care of you if you take care of them. You sit in them and not on them for one thing. My wife and I have owned our 14 footer for about 26 years now and have enjoyed many adventures in it. Yes, they are a chore to take care of…but that’s part of the pleasure for us.

Tyee 1

Tyee 2

The Cosine Wherry that I built looks very much like this from a little distance and handles similarly to the description.

I bought a B&S Whitehall in Maine in about 1970. It’s a fiberglass hull trimmed out with mahogany seats, rubrails, inwales, and breasthook. The mold was taken off a wooden one as, in the right light, one can even “see” the planks in the hull (often people say: Oh, it’s wooden boat, but alas it is not). It has seen water under the keel in Lake Michigan, Lakes Mendota & Monona, Vermont lakes, Maine sea waters, northern Ontario’s Lake Matinenda and more. It has served me well for over 50 years — a real joy to go pulling. I was the very first to order some oars from the Apprenticeshop (So says Lance Lee, both then in Bath) and they too continue to serve me well.

Side note: I used a credit card to get a cash advance to pay for it and it took many months for that transaction to show as a bill in mailbox—oh how times have changed.

This is beautiful. I bought Catspaw dinghy plans from WBS but built it lapstrake instead of carvel. Great fun and it looks similar. I have average skills and it is an achievable project.