The Ohio and the Lower Mississippi rivers had carried me and my sneakbox, LUNA, 1,840 miles in the 57 days I’d spent rowing from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. On January 5, 1986, 3 miles downriver from where I’d spent the night moored between pilings under a downtown wharf, I left the Mississippi at the Industrial Canal locks. The lockmaster wouldn’t let me enter on my own—there were too many tugs and tows that needed to get through.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe lockmaster wisely prohibited me from bring LUNA into the locks unaccompanied. Captain Duffy of the towboat LEAH was my escort.

The skipper of LEAH, one of the tows waiting to enter the lock with its raft of barges, had overheard my conversation with the lockmaster and stepped out of his second-story wheelhouse and motioned me to come alongside. Two deckhands took my lines, set LUNA against a set of truck-tire fenders, and I climbed aboard LEAH to join Capt. Duffy for the passage through the locks.

Nathaniel Bishop, whose book Four Months in a Sneak-Box inspired my sneakbox voyage, left New Orleans by way of the New Basin Canal, which was in use from 1830s to the 1940s. It took him to Lake Pontchartrain where he rowed east to The Rigolets, a pass that opened out onto the Gulf of Mexico.

In some places the marshes spread out for miles. Along the canal, the dredge spoil seemed to be almost all shells.

Over the next 8 miles beyond the locks, I rowed eastward along the Gulf Outlet Canal, part of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), and passed the long taper of the crenellated New Orleans skyline, from the downtown high-rises to the squat industrial buildings, until all that was left of the city was a road on top of an arrow-straight levee flanking the north side of the canal. All around the levee there was only salt marsh, miles-wide expanses of hip-high cordgrass, cigar-brown and immobile in the breeze like a drought-brittle prairie. The bayous that veined the marsh provided dozens of safe havens from the boat traffic in the canal, and at the day’s end I rowed into one just far enough to have a loop shield LUNA from boat wakes. I stowed the oars on deck and cleared the cockpit to spend the night on board.

Fort Macomb, built of brick in 1820, in such a sad state that it is closed to the public.

In the morning the decks were flocked with thick frost. I hadn’t covered the cockpit to protect my sleeping bag, but I’d slept warmly anyway. The wind had shifted to easterly during the night and was tearing straight down the canal. Any other direction would have made for good sailing, but instead I rowed all day into a headwind. All along the shore, scattered on matted salt grass, were carcasses and skeletons of nutria, aquatic rodents that look like beavers, right down to their pumpkin-colored teeth, but easily identifiable by their long round rat-like tail. The nutria as well as the beaver and the headless rattlesnake I found along the canal must have been victims of one of the hurricanes that had swept the Gulf Coast the previous fall. Right in the middle of the marsh I passed the grass-crowned Fort Macomb, built in 1822 to guard a pass into Lake Pontchartrain. It didn’t look like it had ever seen action—its curved brick wall was unscarred.

The captain of a passing tug stepped out of the wheelhouse two stories above me to yell, “You ought to have a little motor!” I pointed to my oars. It left me baffled. He must not have considered that great things are possible with oars and that someone might be perfectly content to use them.

This elevated structure was in bad shape when I saw it, but it remained standing for at least another 29 years. A 2016 satellite photograph on Google Earth shows it collapsed and awash.

At the end of the canal, I arrived at what might have once been the main and upper deckhouse of a tow boat elevated on 40′ stilts of badly rusted steel pipe. I climbed the stairs carefully, testing each one to see if it could support my weight. The handrail was loose and so rusty I could have kicked it off. From the top, I could see out into Lake Borgne, a saltwater lagoon open at its east end. It was my first glimpse of the Gulf of Mexico.

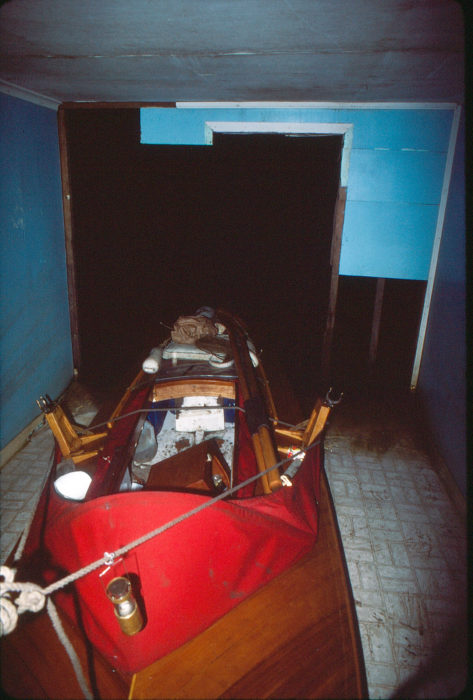

The badly listing houseboat turned out to be a fairly good place to spend the night. LUNA had the bedroom to herself.

I got back in the boat safely and rowed alongside a railroad bridge across The Rigolets, a 3⁄4-mile-wide pass to Lake Pontchartrain to the opening of Little Lake, an enclosed saltwater bay a mile wide and over 2 miles long from west to east. I bucked whitecaps and a stiff headwind until I reached the lee of its east side. By the time I reached the gap to the Pearl River, it was dark and beginning to rain. I saw a camp on stilts on the right bank, but the canal leading to it was shallow and could be dry on the morning’s low tide, so I opted for a houseboat that had slipped off one of its two steel-cylinder floats. The whole house listed at 20 degrees, and the bottom of its north side was in the water.

The hole in the river-side wall turned the bedroom into a garage for the sneakbox.

The wall of the bedroom had been torn out and left an opening wide enough for LUNA, so I pulled her in. I needed a level surface to sleep on, so I ripped the front door off its hinges—putting a rock between the edge of the door and the jamb and closing the door made quick work of pulling the hinge screws out—and propped it up in the living room with a TV stand. It was an interesting view from inside out the windows, seeing the river water up to the horizon two-thirds of the way up the window frame. I was well sheltered from the rain, but I didn’t get much sleep with the wind rattling loose tin on the roof.

I usually leave my campsites at least in as good shape as I found them, but after tearing the front door off its hinges to use it as a sleeping platform, there was no putting it back in working order.

Getting the boat out of the bedroom in the morning was tricky with wet boots on the sloped linoleum floor, but I got aboard without sliding into the river. I rowed along the Pearl River, in rain and headwind again, to Campbell Outside Bayou, a winding 50-yard-wide passage that should have been a pleasant meander, but the marsh grass was so low it provided no protection from the wind. Some 2-1⁄2 miles and 25 sharp bends in, I stopped at a marina for a break. Two trappers arrived about the same time in a jonboat filled with muskrats and nutrias. One of the trappers said the pelts sold for $3 apiece in New Orleans where they’re made into fur coats. The other trapper swished a nutria in the water and tossed it on the bank. It flinched when it hit and then stiffened, not quite dead. Another’s broken leg bone stuck out.

I rowed more bayous in a generally eastward direction, keeping close track of my position bend by bend to avoid getting lost in the web of intersecting bayous that all looked the same. The last of them, Three Oaks Bay, delivered me to the open wind-raked waters of Mississippi Sound. At its mouth, the banks of the bayou turn away from one another and the passageways of canals and bayous from New Orleans open out to the enormous atrium of the Gulf of Mexico. The press of an east wind coming from the unbroken curve of a distant horizon tumbled the waves and bowed the marsh grass at the land’s edge.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

It was too rough to continue, and while I was stopped at the mouth of the bayou, an inbound fisherman came alongside. He was in a work-worn ’glass runabout with a half-dozen frayed-fiber holes worn through the hull at the gunwale. He asked if I was okay. I was and told him I was just a bit cold. He spread the tarp and blankets that he had wrapped around his shoulders and said, “You get the wind off you, ’n’ that’s all you need. Well, if I can’t be of any help to you, I’ll be going.”

I backtracked up Three Oaks to a feeder bayou with just enough clearance either side to row into. I listened to the weather radio as I started to set up camp, but after hearing sleet and freezing rain was coming I decided to move, and repacked. It was only 2 p.m. and I might have time to get to the sheltered marinas at Bayou Caddy, 3-1⁄2 miles to the northeast along the Gulf Coast.

The rowing was always more interesting in bayous and canals where the scenery was close by.

I left the protection of Three Oaks and eased LUNA out through the breakers. Her low bow pierced the waves, and their crests collapsed on the foredeck and fanned out from the dodger like the whiskers of a cat. I turned north, parallel to the shore, and although I rowed 100 yards from shore, the oar blades still caught the bottom when the sneakbox dropped into the troughs. Soon the bottom corners of the coppers protecting the blade ends came up gleaming, polished by the sand.

I kept an eye on the diffuse light of the clouds. As it darkened, I rowed harder. To the west I noted the slip of the foreshore beneath the wooded horizon and gauged my speed. Iron pipes driven into the shoals, markers of some sort, were hidden by the waves but jutted like lances from the troughs. Between strokes the oar blades ricocheted off the tops of waves. I reached the harbor at Bayou Caddy before dark, but my hands had paid a price for the hard row: the fingers of my right hand were numb.

Bayou Caddy was home to the fishing fleet, and the marina was crowded with workboats. Nick, owner of an oyster dredger, invited me to come alongside and spend the night in the boat’s cabin. After he left for home, I stayed up till midnight catching up on letter-writing. Nick was back at the boat at 6 a.m. and fried eggs for my breakfast. I packed up and before I headed out, he drove me 8 miles along the coast, as far as Bay St. Louis to look at the water. It was as I had figured. The wind had shifted to the north overnight, and I would have a bit of a lee to row in.

It was wet going for the first mile. The water was very shallow even 1⁄4 mile from shore. To take advantage of what little protection from the wind the low coastline had to offer, I sounded with the oars frequently, lifting the handles through the middle of the stroke to find the bottom with the blades. The underwater contour I followed gave me a depth of 8″ or 9″ of water. In the shallows the water felt sticky. The LUNA’s underwater wake pulled against the bottom and slowed her as palpably as if she were dragging a chain. Mired in windage and drag, the boat didn’t carry much momentum between strokes; the wash of my oars piled up just aft of the transom as if they’d fallen off the end of a conveyor belt.

I rowed from 8:30 till noon and stopped at Bay St. Louis to use a bathroom. On the broad white sand beaches there was no escaping the notice of people on the beach road and in the houses beyond.

The people I met along the waterways were unfailingly kind. I may have asked just for water but received much more.

I crossed the 1-3⁄4-mile-wide inlet between Bay St. Louis and Pass Christian, and in a race to beat sunset I pulled hard for Long Beach and felt my fingers go numb again. Without an anchor I had no way to hold my ground in the wind but to row. Left on her own, the saucer-bottomed sneakbox would pivot on her skeg and run with the breeze. I was unwilling to rest at the cost of a 1/4-mile row back to shore, so I ate as I rowed. In between strokes I assembled cheese-and-cucumber sandwiches, taking up the oars each time the bow began to fall away from the wind. I stuffed the sandwiches into my mouth by quarters and exhaled through my teeth, shooting breadcrumbs out over the afterdeck.

I came into the Long Beach Marina at nightfall, stupid with fatigue. It was hard to think about what I had to do to get ready for the night, though it had been my routine for two months. I paddled in between the concrete pilings beneath the marina office. I ran the painter over some of the plumbing overhead, a stern line over a cross beam, and tied the ends of both lines to the handle of my water jug to keep tension on the lines as LUNA dropped with the tide. The wind rushed through the harbor, slapping halyards against aluminum masts with the dampened ring of cowbells. LUNA yawed back and forth on her tethers, wagging in the wind like a fish idling in a brook.

For 15 minutes, maybe 30, I tried to find a light to write by. I had left my flashlight behind on Nick’s boat, and my headlamp’s battery was dead. In the clutter of gear in the seat box it was hard to find the candle lantern and a lighter by feel. When I got them and lit the candles, I couldn’t find my pen. Then the candle blew out. After giving myself a minute to feel sorry for myself, I unscrewed the bottom of the lantern to relight the candle, and the glass chimney came loose and the clips holding it fell off. In the dim light from the marina, I was able to get the lantern reassembled and lit, but only after the wind blew the lighter out a half-dozen times. By then my writing pad had disappeared. It had been too long a day on too little sleep.

In the middle of the night, I woke with a throbbing in my forehead, and for some reason it was a struggle to sit up in the cockpit. I discovered the bow line had jammed in the overhead and the falling tide had left the bow, the “foot”of my bed, suspended above the water.

Bishop, spending a night between pilings 12 miles away in Biloxi, had fared much worse. He and a traveling companion in a second boat settled in for the night between pilings under a bathhouse: “About nine o’clock in the evening we passed the Biloxi light-house, and decided, as the night was serene and the waters of the Gulf tranquil, to run under one of the bath-houses, and there enjoy our rest. The piling of some of the piers was destitute of the usual shark barricade, and selecting two of these inviting retreats, we pushed in our boats, moored them to the piles, and were soon fast asleep. About daybreak the weather changed, and the sea came rolling in, pitching us about in the narrow enclosure in a fearful manner. The water had risen so high that we could not get out of our pens; so, climbing into the bath-rooms above, we held on to the bow and stern lines of our boats, endeavoring to keep them from being dashed to pieces against the pilings of the pier. While in this mortifying predicament, expecting each moment to see our faithful little skiffs wrecked most ingloriously in a bath-house, sounds were heard and some men appeared, who, coming to our assistance, proved themselves friends in need. We fished the boats out of the pen with my watch-tackle, and hoisted each one at a time into the bath-house that had covered it.”

I left Long Beach in a northeasterly and worked my way for 5 miles against it to Gulfport Harbor. The tide was still falling, and I dragged LUNA a few boat-lengths up on the hard-packed ash-gray wet sand. I jogged across 200 yards of gently sloped beach and into town to pick up mail at the post office. When I returned to the beach, I saw a man sitting in the sneakbox. I didn’t yell but ran as fast as I could, looping around behind him, to catch him by surprise. He didn’t notice me until I was just a few yards from him. I asked him what he was doing, and he got up. I didn’t see anything in his hands and his pockets appeared empty, so I told him to go away.

I rowed another 13 miles to Biloxi and at the city marina veered southeast to Deer Island, a 3-3⁄4-mile-long sliver of a barrier island set a couple of hundred yards offshore. I landed near a house that was being built on stilts high enough to hide it in the canopy of the long-trunked pine trees. There were stacks of lumber on the sand and pine-needle ground, and there was a wooden ladder to get up to the house. I looked around inside and with all the construction, the only clear space was in what would become the bathroom. I hauled the gear I’d need for the night and settled in. In the mail I’d picked up that morning there was a package from a friend whose mother had sewn a blanket into a sleeping-bag liner. In the shelter of the house and with the extra layer of bedding, I’d have a warm night. I got out of my clothes for the first time in six days.

Sailing wing-and-wing in the navigation channel, I had to peek forward for traffic every once in a while.

It was blowing hard out of the north in the morning, a direction which might have been useful for sailing, but I was leery of pushing my luck in a strong offshore wind, so I rowed back to Biloxi and then across the 1-3⁄4-mile-wide Biloxi Bay to Ocean Springs. I turned southeast and skirted the town, thinking about sailing and keeping a close eye on the wind to see if it would hold steady. I’d waited two days for a northerly reaching breeze. I put ashore on a black muddy beach at Marsh Point and pulled the spars out of the hull through the deck plate in the transom.

Fully decked, LUNA could churn along with her rail under. For such a small boat, she was remarkably seaworthy.

For almost 2,000 miles I had carried the mast, boom, and sprit below decks where their only useful work was to provide a shelf for my foulweather gear. I set the daggerboard on deck and pinned the rudder to the transom. The unmarred varnish of the sailing gear glowed in the soft, shadowless light of heavy overcast. The main and the jib spread out from the spars above LUNA’s cedar deck, and the sails trailed in the wind with the shudder of butterfly wings just emerged from a chrysalis. I slipped LUNA sideways through the shallows while easing the board down. A third of a mile from shore I had 3′ of water, sheeted in, turned LUNA parallel to the shore, and she took off. She made great speed, dragging an enormous noisy wake and occasionally driving the bow under. When the half-lowered daggerboard hit sandy shoals, it hissed like the wheel of a glass cutter.

I sat on the afterdeck mesmerized by the blurred streaks of whitewater around the boat. For two months of rowing, I had been the boat’s engine, and now LUNA had come to life, quivering with the flutter of her daggerboard and charging across the water on her own.

The wind had begun to overpower LUNA, pushing her toward open water, and when I had quickly covered the 5 miles to Bellefontaine Point, I steered into the shallows and luffed, pulled the daggerboard out, and stuck a 6′-long 1×4 I’d found on Deer Island through the trunk and into the sand to keep the boat from drifting. After I brought the rig into the boat, I rowed toward shore. The rain had not stopped since the previous afternoon, and I had gotten cold, even in my slicker with a scarf gasketing the collar.

The Navy’s Aegis Cruisers being built at a Pascagoula shipyard have sweet hulls and forbidding superstructures.

Rowing would warm me up, and in heavy rain I pulled across Pascagoula Bay and past Ingalls Shipyard where Aegis Cruisers were being built for the Navy. A high-pitched whistle in a discordant series of four tones came out of nowhere, so loud that it seemed like tinnitus coming from inside my head. The Navy must have been testing something. A patrol boat had spotted me and got on a bullhorn to tell me to leave.

Just beyond the shipyard I rowed up behind a fisherman at anchor along the shore. He was a bit startled to see me. “Where’d you come from?” When I answered “Pittsburgh,” he started laughing. He’d seen a few other oar and paddle cruisers, but I had come the farthest. I asked him about the post office, and he pointed me to Lake Yazoo, a Y-shaped inlet nearby. There were a lot of sailboats at private docks there, and I picked the one by MIMI, a wooden cutter, to tie up to. Above the pier was a large old house. I rang the doorbell at the water side of the house. No answer. I walked around to the other side and met Andrea, who had been at the front door wondering why the doorbell was ringing after she had peeked in the window.

“I don’t know what you’re doing here,” I said, “but I’ll tell you what I am doing.” And she started laughing at Pittsburgh, too. She drove me to the post office, the grocery, then to her brother’s restaurant for chili, then back to the old house, where we visited Michelle, who lived there with her husband, a son, and parents. Then Andrea took me home to meet her mother and stay as a guest for the night. We sipped sugar-free Kool-Aid while watching Johnny Dangerously on VHS tape.

The following day, I set the rig up on the beach and sailed out through the shallows outside of Lake Yazoo, dragging the rudder in the sand. Once I got to deep water here, 6′ is deep—I set the board halfway down and took off on a broad reach. In 3 miles I rounded the corner below a refinery and hit a submerged sandbar at full speed. If the bottom had been rocky and more abrupt, it would have been a violent, damaging impact. South of the village of Coden I got across Mississippi Sound on a beat, with water flying over the bow. I sat on the windward deck while the breeze was stiff, flying; when it slacked off, I sat in the cockpit.

A line of land appeared as a slender charcoal smear on the east horizon, and I bore away toward its end. I passed the low marshy Isle aux Herbes, and when I got near the 1⁄4-mile-long crescent of Cat Island the wind faded, shifted 180 degrees, then dropped altogether. I dropped the rig and rowed 6 miles to Dauphin Island, arriving at sunset.

I pulled in at the first house I saw with lights on to ask if I could use the phone to make a collect call home, and two couples—Bill and Carole, John and Jeanne—took me out to dinner. I had a seafood platter and gumbo. After dinner, Carole insisted I sleep inside. I brought my bedding in from the boat and set up in the living room. After everyone else turned in I could scarcely breathe. The house was heated to 70 degrees. I gathered up my bed and slept out on the porch.

At the west end of Choctawhatchee Bay I rowed under one of the bridges in the 3-1/2-mile causeway that spans the bay.

My hosts saw me off in the morning, and I rowed off and made the 3-mile crossing between Fort Gaines on Dauphin and Fort Morgan, the two forts that guarded the entrance to Mobile Bay during the Civil War. The sun was bright and the air was still, so I stripped down to air out my clothes and myself as I rowed across Bon Secour Bay. At sundown I rowed into a little condominium harbor just past the entrance to Portage Creek, a 9-mile-long canal, and tied up along a Parti-Kraft pontoon boat with its padded chairs and recessed drink holders.

When Bishop arrived here in February 1875, there was no canal, and as the name of the canal suggests, the creek could only be reached from the west by an overland portage. Bishop hired a farmer for $5 to haul his sneakbox from the end of Bon Secour Bay.

“We travelled slowly through the heavily grassed savannas and the dense forests of yellow pine towards the east, in a line parallel with, and only three miles from, the coast. The four oxen hauled this light load at a snail’s pace, so it was almost noon when we struck Portage Creek near its source, where it was only two feet in width. Following along its bank for a mile, we arrived at the logging-camp of Mr. Childeers. There we found the creek four rods in width, and possessing a depth of fifteen feet of water. The boats were soon launched upon the dark cypress waters of the creek, the cargo carefully stowed, and the voyage resumed. Though the roundabout course through the woods was fully seven miles, a direct line for a canal to connect the Bon Secours and Portage Creek waters would not exceed four miles. About two miles from the logging-camp the stream entered ‘Bay Lalanch,’ from the grassy banks of which alligators slid into the water as we rowed quietly along.”

The row within the walls of the canal the next morning was a welcome change of scenery. Rowing along the coast of Mississippi Sound, I had been too far from land to find any diversion to take my focus off the sluggish labor of rowing into the wind. Halfway through the canal, I passed through the wooded residential outskirts of Gulf Shores, then arrived at the end at Wolf Bay.

I could feel a gentle northwesterly blowing and beached LUNA on the smooth slope of tawny sand to set sail. As I was about to shove off, a tug and barge appeared from around the bend to the west. I was surprised to see the water pull away from the beach like the sudden low tide that precedes a tsunami. I was expecting a surge of water from the barge’s bow wave, but evidently it pulls the water ahead of it to pile up into the wave.

While the wind stayed brisk out of the north and northwest, I made good speed sailing on a reach across Wolf Bay and, 5 miles farther along on the same point of sail, Perdido Bay, where I crossed from Alabama into Florida, and then through the 150-yard-wide gap between Perdido Key and the mainland. The miles continued to slip by, and I crossed Pensacola Bay with dolphins racing beneath the hull, their sleek gray bodies blurred by the water like figures seen through the textured glass of a shower door.

Sailing on the Gulf, sometimes only a mile or more from shore, felt like being at sea, but the water was so shallow that I rarely fully lowered the daggerboard. Its top end is visible here.

I was flying for hours on end and with a good puff of wind, LUNA got on plane and left a wake that would have done an outboard proud. It made me laugh to see that kind of speed. The mainsail took a beautifully clean shape with the sprit to windward. I spent most of the day on the port deck, leaning against the oarlock stanchion, steering with my hands on the tiller lines. At speed there was a lot of pressure on the rudder.

As the sun went down, I headed for the north shore of Santa Rosa Sound, landing at a beach 46 miles from where I’d set out in the morning. It was a new coastal-water record for me. I camped in the boat, happy to be sitting on the sand eating beef stew under the stars.

I woke to frost on the deck again and got rowing in the rose-pink half-light of dawn on a preternaturally still Santa Rosa Bay. The overlapping ripples left by the oars made moiré patterns fanning out from the trail of bubbles in the wake. I frequently watched over my shoulder hoping to catch the first glint of sunlight but missed it. A westerly picked up mid-morning, not the NE that the weatherman predicted. I set sail on a small bit of sandy dredge spoil along the channel. While under sail later that morning, I fiddled with the tarp, to make a spinnaker out of it to take advantage of the tailwind. I raised the tarp along with the jib on its halyard, and the board I had been using as a marsh stake became the spinnaker pole. The extra sail area made a difference, and LUNA took off dragging a water-skier’s wake. In the narrowing east end of the sound, I had to drop the chute to sail on a reach to the next mark a few times, and got pretty good at dousing and resetting it.

By midafternoon I drew near Walton Beach. I hit a shoal at speed and stopped dead, but the wake came up from behind me and lifted LUNA over the hump. I landed at a bit of a beach, where I met Dean as he was working on a boat he sails as advertisement and yacht for a restauranteur. He took me to the post office for mail and to a burger joint for lunch.

I took off again in 15 knots of wind and headed into Choctawhatchee Bay. LUNA speared into waves and ran right through them; water coming over the foredeck poured over the sheer with a long, gravelly roar. To keep the bow up, I shifted my weight aft and rode the afterdeck like a luge racer, looking over my chest at the course ahead. Froth streaking past the transom heaped up white astern. I buried the bow often and slowed down suddenly but avoided broaching or pitchpoling. As I clipped close by Cobbs Point, I saw the amber water brighten over a shoal. The daggerboard, only halfway down to dampen the roll, hit the sand and I pulled it up in its trunk, and the sneakbox skimmed through 8” of water. The boat slowed with the drag of water pinched beneath the hull, the sheets quivered, and the stern wake shortened and crested, milky with the sand stirred up by the rudder.

I enjoyed sailing LUNA so much that I often took advantage of the protected inland waters to sail past sunset into the night.

As I crossed the widest part of the bay, the sun touched the horizon and melted into it. I had sailed 37 miles since morning and had 8 miles to cover before I could go ashore at Four Mile Point on the south side the bay. I sailed through dusk into night until the quarter moon cast the shadow of sprit on mainsail. I held my course by keeping masthead in the Pleiades; Orion stood by alongside the spinnaker as I surfed down waves I could not see. After three hours on the afterdeck, I was straining to keep my head up, and my hands ached from gripping the tiller lines. I would glance at the chart by flashlight while the boat paused at the crest of a wave, checking my position before throwing my weight aft against the fall of the bow into a trough. I dropped the spinnaker as I approached Four Mile Point and turned into its lee. I had covered 48 miles and been underway for about 12 hours when I finally poled along the shallows with an oar and camped in the boat beneath the whisper of wind through the pines above me.

From my camp in the woods of Four Mile Point I rowed past scrubby end of Live Oak Point in a glassy calm. If I squared the blades on the recovery, the invisible vortices of air curling off them left V-shaped trails on the water. I passed a scattering of workboats where oystermen were pulling up their harvest with long-handled tongs that they worked like oversized post-hole diggers. In warm still air I rowed long strokes and let LUNA glide.

At the east end of Choctawhatchee Bay, I entered a crooked 22-mile-long canal flanked with 30′-high white sand walls where high ground had been cut through for the waterway. It was warm in the still air of the canal, and I stripped down to shorts. A big cabin cruiser sped by with its two crewmen bundled in parkas, scarves, and gloves. I stared at them and they stared at me and, baffled by the contrast, none of us spoke or waved.

Late in the afternoon I rowed along a channel that was cut across what used to be the meanders of West Bay Creek, leaving a few quarter-moon islands flanking the main channel. I stopped at the small town of West Bay where I bought a can of root beer and a package of cookies.

The sun had just dropped behind the trees when I reached West Bay, an 8-mile-wide hourglass part of the inland waters surrounding Panama City. Cormorants crowded atop the channel markers dropped from their perches as I approached and hit the water running before they could take flight. The surface of the water glowed like molten metal, reflecting the blaze in the evening clouds. The fins of dolphins cut dark streaks across the sneakbox’s wake. They surfaced around LUNA just out of oars reach, close enough for me to see their small dark eyes tucked beneath the domes of their foreheads.

Had there been the slightest touch of wind, I would have been off the water by dark, but the lights of Panama City, 8 miles away, streaked the bay with white and red lights and silhouetted the obstructions ahead of me. I could even see the buoys of crab pots. I kept to the shallows, away from the erratic courses of oyster dredges still working the middle of the bay in the dark.

I reached Panama City late that night, at the end of a day’s row of 47 miles, and passed by the concrete-walled Dyers Point and entered the marina at Buena Vista. Under the harsh pale-orange sodium-vapor light buzzing at the end of a pier, I centered LUNA under a line between two pilings. I started singing the “Hallelujah Chorus” from Handel’s Messiah, and a half-dozen dolphins surfaced astern and then moved up on either side just beyond the ends of the oars. Their heads and fins were silhouetted in a reflection of the sky that was amber as white sand under tannin-stained swamp water. When I started in on “Home on the Range,” I lost my audience.

Many of the beaches in the urban areas of the Gulf Coast are made of sand pumped ashore. This natural beach near Panama City, unfrequented by tourists, had lots of shells and was much more interesting.

In the wee hours of the morning, I woke up and noticed that a black skimmer was fishing the water around my boat, flying with the lower half of its beak at an almost vertical angle, making a slender wake. Its shoulders were angled above its head to get the clearance for its wingtips and, in time with the beating of its wings, the sound the beak made was like the pulsating hiss of a pressure cooker with its weight rocking on the vent. The bird came back and, like a crop-duster, made each new furrow parallel to the last. I didn’t see it catch anything.

The canal was conceived in the early 1800s but wasn’t dug until after Bishop’s voyage. We rowed to Cape San Blas and had a 1/3-mile portage over the narrow peninsula there. It was a long climb to put my camera, tripod, and radio remote at the top of the cut; excavating the high ground to make canal must have been an extraordinary feat.

From Panama City, the ICW runs the length of East Bay and enters a 21-mile canal cut through land that was marked on the chart, from west to east, as Low swampy area, Swampy area, Cypress swamp, and, finally, Impenetrable swamp. I camped in the west end of the swamp to make sure I’d get through the rest of it before dark. When I got under way early the next morning, I passed two fishermen aboard a sparkling purple metal-flake hull with green artificial-turf decks at sheer level. They were slouched in chairs that looked out of place without office desks; they swiveled like gun turrets keeping their eyes trained upon me as I rowed by.

The farther I progressed into the canal, the closer together the cypress trees grew. Here in the “Impenetrable swamp,” it was true anyone would be hard pressed to travel far on foot.

“I’d have me a motor on that thing,” one of them said. He had a motor on each end of his boat, a skinny chrome-pipe trolling motor on the bow and a white-and-blue outboard on the stern with a mushroom-shaped power head as big as a washtub.

The “Impenetrable swamp” indicated on the chart turned out to be only as menacing as I could make it.

I found a loose cypress knee that was just big enough to wear after I scraped out the mud-wasp nest inside it. At the time, it had slipped my mind that there might be alligators in the area.

I reached the impenetrable part of the swamp where the trees had woven their roots and branches together into a barrier so dense that even sound couldn’t get far into it before its echo retreated to the waterway.

I crossed Lake Wimico late in the day, but the rowing conditions were ideal and I continued rowing until well after dark.

I came out of the confines of the swamp at Lake Wimico and reached the Jackson River at the opposite end of the 5-mile-long lake by nightfall. With only the light of the stars I could see the course of the river if I looked toward the banks and at best could see the pale streak of the water with my peripheral vision. Soon I felt the pull of the tide drawing me toward Apalachicola Bay. Sitting on the afterdeck, I let LUNA drift in mid-channel while I set the stove in the cockpit and heated up a dinner of canned beef stew. It was quite late, well after 9 p.m., when I reached the harbor of Apalachicola. The amplified squeal of an electric guitar, played by someone in town with more watts than talent, soured the night air with a miasma of sound.

After spending more than two months aboard LUNA, I got used to sleeping aboard, even with the hatch cover in place. There was only 14” of space between the hull and the cover, so it wasn’t for the claustrophobic. When Captain Hazelton Seaman of West Creek, New Jersey, built the first sneakbox in 1836, he called it the Devil’s Coffin. It does have that feeling when the lid is on.

I found an inlet with a pair of pilings I could tether the boat between, and settled into the boat with the hatch cover slightly propped up over the cockpit coaming against the chance of rain in the forecast.

In the gray drizzly morning of January 18th, I rowed the last of the Intracoastal Waterway past riverside business district of Apalachicola and across the 4-1⁄2 miles of East Bay to Eastpoint, an oyster town that had been gutted by hurricanes earlier in the winter. The backs of the oyster-shucking houses had been torn open by the wind and storm surge, and their walls and interiors had spilled over the mounds of shells along the shore. Eight miles up the coast at Royal Bluff, tattered clothing washed ashore by the hurricane and anchored in the sand at the water’s edge swayed like seaweed in the back-and-forth wash of the waves.

I made a stop in Carabelle to find a hardware store where I could buy an anchor. I had a lot of open water ahead, and an anchor would be my insurance against being driven into open water by an offshore wind. From where I came ashore for the night, I could see Dog Island, 4 miles from the mainland across Saint George Sound, as a black wisp of an edge on the horizon to the southwest. It was the last of the barrier islands, and beyond it I’d be on the wide Gulf of Mexico. At nightfall, I settled in the cockpit with a candle lantern I’d made from a soup can hung from the coaming.

The next day, I sailed with a stiff wind gusting southwesterly between the surf-whitened shoals off Turkey Point and Alligator Point, and rounded Southwest Cape to head north into the sheltered waters of Ochlockonee Bay. Turning at the cape I trimmed the sheets from a run to a close reach, and the sneakbox strained uneasily under the increased pressure of the wind. I let the sheets fly and dropped anchor. The bow came quickly into the wind as the blunt but heavy cast-iron flukes of the anchor I’d just bought bit into the sand bottom. With the rig dropped and secured on deck, I brought up the anchor and rowed hard for the safety of the lee and then crossed the bay to call it a day at the easternmost of five artificial inlets that had been cut to make a condominium community.

I rowed out from Ochlockonee Bay before sunrise on the morning of January 20th. I was a bit worried about what I had ahead of me—Florida’s Big Bend where the state’s panhandle turns into the peninsula, over 50 miles of uninhabited coastline with a mile-wide fringe of marsh backed by swampland with cypress trees as dense as fence pickets.

Bishop, apparently, never sailed during his voyage. I think he missed some the best the Gulf had to offer.

A northwesterly breeze darkened the waters of Apalachee Bay, and I stowed the oars on deck and stepped the mast. The main and jib unfurled to catch the cool breeze and the warm light of the morning. I headed for the farthest point of land I could see and held my course almost 2 miles offshore to keep enough water below the daggerboard. I made good speed past the tapered white tower of the St. Marks Lighthouse, the only landmark at the apex of the bay. For 20 miles beyond it, the coast had no distinguishing features that I could use to determine my location. The marsh and the cypress forest of the swamp was a stripe of dark green and black where every mile looked exactly like the miles that came before it. The wind veered around behind me, and I set the tarp-spinnaker. The breeze held through the morning, and the miles streaked beneath the hull of the LUNA as I began to turn southward by slow degrees.

Even with the sprit (seen here at the bottom) removed and the mainsail folded in half—“scandalized”—LUNA made good speed.

Some 30 miles into the day’s sail, I picked out two clumps of trees 1⁄2 mile from shore that were the twin Rock Islands, brought them abeam, and left the below the horizon astern. As the breeze backed and came out of the west and my course turned from east to south, I pivoted the marsh-stake/spinnaker pole over the bow and set the tarp to pull on a broad reach. In the late afternoon the breeze stiffened and came over the starboard beam. I dropped the chute and a while later pulled the sprit from the main and folded the peak down, reducing its sail area by more than half. Even with the shortened rig, I reached along at a good speed.

Late in the afternoon LUNA was back under jib and full main, and I continued along the coast. When the sun dropped behind the sweeping horizon of the Gulf, I sailed by moonlight. After 52 miles under way, I headed toward shore on the reflected light of the town of Keaton Beach. I had sailed the Big Bend nonstop in one go.

I landed on a beach in front of a restaurant, having used the reflections of its lights to find a clear path to shore. The smells coming out of the restaurant drew me inside just as its lights had brought me in from the water. After dinner I rowed into a canal on the other side of the town and spent the night in the boat.

Bishop noted in his book that his sneakbox, CENTENNIAL REPUBLIC, had been built to sail: “with spars, sail, oars, rudder, anchor, cushions, blankets, cooking-kit, and double-barrelled gun, with ammunition securely locked under the hatch, the Centennial Republic, my future travelling companion, was ready by the middle of November for the descent of the western rivers to the Gulf of Mexico.” And yet he made no mention of sailing at any time during his voyage. During my one-day passage around Big Bend, I passed by four of the campsites he wrote about and landed a fraction of a mile from his fifth. While I only sailed about 200 of the 2,400 miles I traveled, I would have happily carried the rig for just that one day at Big Bend and those 52 miles.

The last two days of my voyage were serenely quiet. Even though I was rowing and didn’t need deep water for sailing, I stayed well over a mile offshore just to be in waist-deep water.

To take the “selfie” above I only had to set the tripod in the 3’-deep water and trip the shutter with a radio remote.

The wind faltered the next day as I made my way south from Keaton Beach across Deadman Bay. Large flat-iron skiffs planed across the bay. Their skippers stood in the bows to see their way through the shallows, giving their craft the look of aquatic minotaurs. Gray tracks of sand crisscrossed the eelgrass-covered shoals where their outboards dragged along the bottom. I stopped for the night in the shelter of one of the many manmade inlets of the town of Horseshoe Beach.

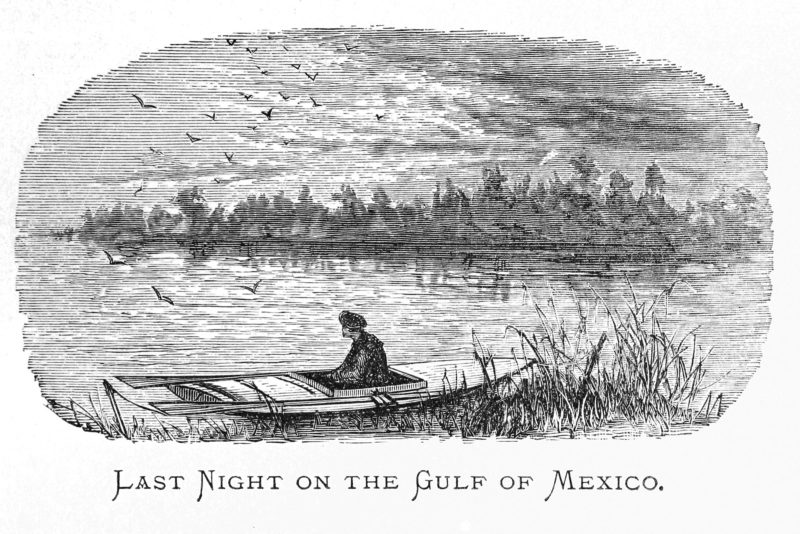

Bishop wrote of the last night of his voyage in 1875: “Lying there under the tender sky, lighted with myriads of glittering stars, a soft gleam of light stretched like a golden band along the water until it was lost in the line of the horizon. Beyond it all was darkness. It seemed to be the path I had taken, the course of my faithful boat. Back in the darkness were the ice-cakes of the Ohio, the various dangers I had encountered. All I could see was the band of shining light, the bright end of the voyage.”

In the glassy calm of January 23, I rowed to the mouth of the Suwanee River and passed Bradford Island, where Bishop had spent the last night of the voyage he chronicled in Four Months in a Sneak-Box. A year earlier, in 1875, he had emerged from the Suwanee in his paper canoe at the end of his 2,500-mile voyage from Quebec, just as I had in 1984 in my own paper canoe, which I paddled along the route Bishop had described in Voyage of the Paper Canoe.

On the last day I rowed to Cedar Key in flat water. To get this photo in the pre-drone era, I secured my 35mm SLR to the sprit and raised the sprit alongside the mast. For the image here I blended two slide scans in Photoshop to remove the spars.

I took the first step on the path that brought me to this beach in the summer of 1982 when I read a magazine article about Nathaniel Holmes Bishop. I followed that path for four years, built two boats, and paddled, rowed, and sailed nearly 5,000 miles in his wake.

The spider-like water tower of Cedar Key soon rose from the last horizon I would row LUNA to. I threaded my way through the maze of reefs and islets of Suwanee Sound to a beach on the south shore of Cedar Key, where I’d mark the end of my 2,400-mile voyage. In the cool of the afternoon, the moon and sun balanced in the east and west, the sneakbox LUNA coasted to a stop. I stepped ashore quietly with a years-long dream fulfilled.![]()

Epilogue:

In January of 1984, in Toms River, New Jersey, I caught up with Nathaniel Holmes Bishop III (1837 to 1902) after completing my 2,500-mile retracing of his Voyage of the Paper Canoe. In 1990, my son was born and named Nathan in remembrance of the man I had followed for almost 5,000 miles.

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

A remarkable tale in every aspect. The story speaks for itself. I felt I was there beside you throughout the journey. Thank you, Mr. Cunningham.

Great story, thanks! Some aspects remind me of my own small-boat cruises, or of the Melonseed Skiff I owned.

Thoroughly enjoyed reading the account of your epic journey in LUNA.

Given its unique feeding method, I think the bird you watched “in the wee hours of the morning” was almost certainly a Black Skimmer, rather than a Shearwater.

What an amazing bird, they don’t occur here in the UK but I remember watching them on a birding trip I made to Mexico in the early 2000s

Best regards

Paul Pearson

Thanks, Paul. It was indeed a Black Skimmer. I’ve made the correction.

Thanks for the editorial and the Sneakbox articles. I grew up in New Orleans and was fortunate enough to sail in the lake and canoe/kayak in the bayous with my dad and go fishing in the marshes with my grandpa. Will definitely try to inspire this adventure in my kids. Thanks!

As a lifelong boater and reader of nautical adventures, I can say your three-part series on your sneak-box adventure is a wonderfully written contribution to our nautical literature. I went back and copied out many of the strong lines in your narrative. I won’t repeat all of them here but since I have fished Deadman Bay for 45 years I will repeat your description of the local net fisherman tiller steering their outboards mounted in the foredeck from the bow. “Their skippers stood in the bows to see their way through the shallows, giving their craft the look of aquatic Minotaurs.” Writing the equal of Nathaniel Bishop. Thank you for the sensitive descriptions of the indigenous southerners.