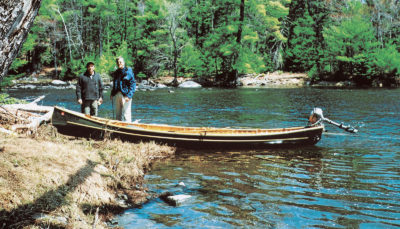

Shearwater might well be the best all-round pulling boat at the WoodenBoat waterfront—at least she was, before we installed a centerboard trunk.

When Joel White drew this elegantly simple 16′ double-ender, he recalled the traditional boats of western Norway. (At first, he named the new design “Joelselver.”) The hull’s narrow breadth at the waterline permits a slender immersed shape. Above the water, Shearwater’s sides rake outward, which provides buoyancy and reserve stability for the able little boat. The strongly raked sides also produce sufficient breadth at the rails for efficient long oars. Deliberately low freeboard reduces windage, and wind is a persistent enemy of oarsmen. Shearwater makes good speed when pulled with moderate effort, and she carries (glides) well between strokes.

A slight touch of rocker (fore-and-aft curvature) to the keel gives maneuverability, but this skiff retains adequate directional stability. Shearwater can turn quickly, and yet she handles well in a following sea. Boats with dead-straight keels and sharp ends might get us to windward quickly, but they often transform into tripping and broaching monsters when we’re running off.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzShearwater, shown here under oars with her push-pull tiller stored aboard, rows beautifully. Her rig might be considered auxiliary propulsion, while the oarsman is the primary engine.

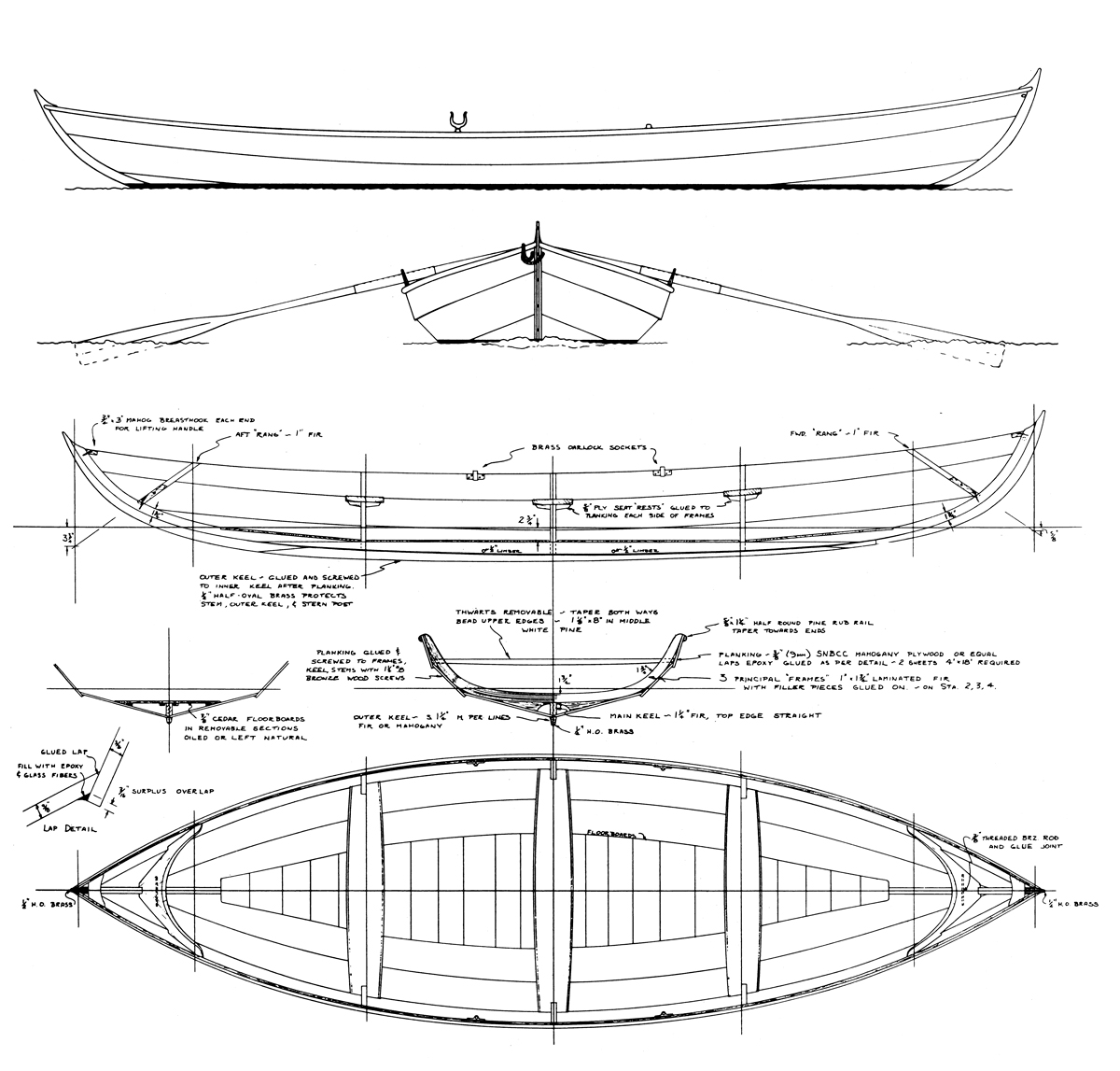

This plywood-lapstrake skiff goes together easily. WoodenBoat School students built our boat in less than two days. The eight sheets of building plans include full-sized paper patterns for frames and other components. Lofting, that is re-creating the hull lines at full scale, is not required…but paper has a nasty habit of shrinking, stretching, and slipping. Unless you work in a climate-controlled shop, you might want to redraw the lines on the floor or on sheets of white-painted plywood.

The act of lofting is inexpensive, educational, and clean. Many of us consider it good fun. Perhaps most important, it allows us to build the boat in our minds before cutting into costly mahogany plywood. For a friendly primer on this subject, see the “Lofting Demystified” section of Greg Rössel’s book Building Small Boats (WoodenBoat Publications, 1998).

The hull’s strakes (three per side) hang on three laminated frames. This glued-lapstrake hull almost demands the use of epoxy as an adhesive—for its gap-filling properties as well as its strength. While the epoxy cures, we’ll temporarily secure the strakes with steel drywall screws driven through the laps along the entire length of the hull. Let’s not forget to remove these ferrous fastenings, and to fill the resulting holes, sometime before painting. Where the strakes cross each frame, we’ll employ bronze screws. These fastenings of eternal metal will remain in place for the life of the boat.

Joel White drew a standing lug rig to provide auxiliary propulsion for Shearwater. This simple arrangement offers low-centered, easily controlled power and short spars that can stow in the boat for trailering. Unlike most modern rigs, it requires no standing rigging (stays, usually of wire rope, that support the mast). We’ll need only a little store-bought hardware. Just two blocks (pulleys) are specified on the plans.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzRigged for sail, Shearwater makes a handy camp-cruiser. The one shown here, a larger, deeper 18′ version of the original, explored islands in Maine in mid-August.

Take some care in sewing and setting the lugsail. It appreciates having sufficient draft (don’t cut it too flat), and it likes to have the halyard secured to the yard in just the right place. Casual experimentation during the first few sails should reveal the proper setup. Keep sufficient tension in the luff (the sail’s leading edge) by tightening the downhaul (a short line at the forward end of the boom). As the yard comes down at day’s end, it does so head-first. Grab hold of that stick before it takes aim at your head. Minor cautions aside, this rig seems reasonably tolerant of inattentive setup.

After we become accustomed to the Norwegian-style push-pull tiller, Shearwater sails fast and handles well in light and moderate air. As the breeze comes on, the helm gets heavy and the bow begins to punch through waves. It’s time to strike the rig. Joel knew well the foolishness of pressing a low, narrow, undecked skiff in strong winds. He viewed this skiff as a pulling boat, with auxiliary sailpower.

WoodenBoat’s Shearwater spent two years as a pure pulling boat. Then, yielding to temptation, we commissioned the addition of sailing gear. The resulting clutter of spars and the hydrodynamic drag caused by the centerboard trunk degraded the boat for rowing.

If we look at Shearwater’s bottom, the narrow slot into which the centerboard retracts appears harmless. In fact, it generates considerable drag. A long time ago, I rowed and sailed prototype fiberglass skiffs that had been laid up without gelcoat (the opaque, and often colorful, outer layer of pigmented resin seen on most ’glass boats). The translucent hulls allowed us to study water flow and wave formation as we looked out through the hulls while sailing—educational, and far more entertaining

than network television.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzShearwater is a lithe, easily built adaptation of a traditional Norwegian design—the oselver, or Os estuary boat.

As the boats moved through the water, we observed extreme turbulence in the after ends of their centerboard trunks. When we’re rowing, energy to drive this undulating light show must come from us. Even the strongest man can produce, at full effort, but a fraction of the power available from wind or mechanical contrivance.

After we learned the magnitude of increased drag, sailors worried about loss of speed—even when they were not racing. Oarsmen begrudged wasting their limited energy. In order to reduce drag, we sometimes covered the offending slots with neoprene flaps secured with bronze half-round and screws. Today, I’m told that we might use Mylar tape (slit longitudinally with a sharp knife after being applied to the hull). Perhaps you’ll consider rigging your Shearwater only for rowing. We tampered with perfection and spoiled it.

Although she’s not big compared to other 16-footers, this boat has plenty of room for solitary beach cruising. We’ll row through the morning calm and sail on the afternoon’s breeze. When we hit the beach, we can roll or drag the 150-lb cruiser up and away from danger. After supper, we’ll lift out the thwarts, and the floorboards will make for a comfortable bed. If we’ve rowed a long stretch at a fair pace, sleep should come easily.

Shearwater’s glued-plywood construction will withstand drysailing more handily than her solid wood cousins. She’s lighter, too, making for a more nimble recreational craft.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2008 and appears here as archival material. Plans are available from the WoodenBoat Store for $75 (as of 2022).

Lovely, just lovely.