Time passes and carries with it our memories of even the sweetest experiences. I admit to having forgotten a lot during the past 25 years, but every moment I’ve spent in the company of BLACKBIRD remains firmly burned onto the CD of my life in boats. She’s a nautical treasure and rubs up against the edges of perfection. She may be the most appealing example of her type, a minimalist outboard-powered cruiser for sheltered waters, and the reason (or reasons) she hasn’t spawned a single sibling remains one of the most baffling mysteries of our time.

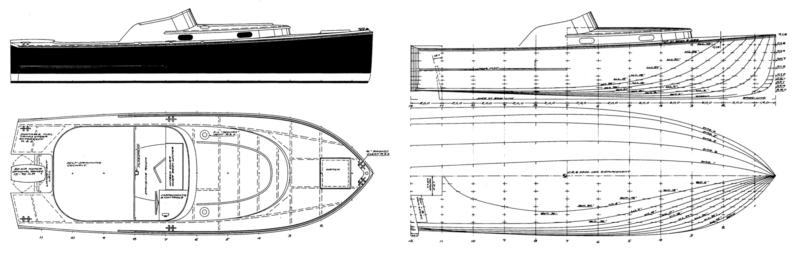

Conceived in the early 1980s by Ken Bassett, Onion River Boat Works, and massaged into her final form by Phil Bolger, BLACKBIRD embodies the spirit of carefree mobility found in the lyrics of the Mort Dixon/Ray Henderson song “Bye Bye Blackbird,” “Pack up all my cares and woe, here I go, singin’ low, bye bye blackbird.” BLACKBIRD evolved on the image of the 40′ launch ESCORT, which Al Mason designed in about 1940 when he worked at Sparkman & Stephens. Bassett latched onto the notion of building a simple, lightweight variation of the theme, which ESCORT so beautifully represents, while he watched slides of a friend’s cruise on the Rideau Canal system in Ontario, Canada. His preliminary drawings showed a hardchined hull that Bassett planned to build from plywood. He sent the drawings to Bolger for completion. Bolger shared Bassett’s admiration for Mason’s graceful launch, and he drew plans for a round-bilged hull measuring 23′ 4″ long overall and 7′ 8″ maximum beam.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

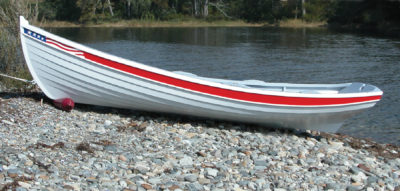

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzLikely the most beautiful outboard cruiser ever designed, the shoal draft BLACKBIRD can cozy up to a secluded island beach and let her crew step ashore.

Approximately three times longer overall than she is wide and, on the waterline, only a few inches shy of her overall length, BLACKBIRD is all about curves—the shadows and highlights of which define her shape as she moves through the water or swings to her anchor. She’s beautiful from every angle, but her relatively short overall length pushes the aesthetic limits. If we chop off so much as a foot, retaining the beam as drawn, we’d be in danger of creating a caricature. If we scale down the design by a foot—which also requires narrowing the beam—we may cramp her interior volume beyond practical use.

On the other hand, scaling up or lengthening her on the same beam would add far more than the numbers indicate. She would be faster, roomier, more stable laterally and longitudinally, more elegant, and more expensive to build or have built. In spite of our preferences—as drawn or longer—we can’t ignore the sound reasoning that established BLACKBIRD’s final dimensions. A lightweight 24′ boat handles easily on the water, tows without protest, and readily cooperates during launching and retrieving. All of these characteristics extend her cruising grounds and enhance her usefulness. I’ve often imagined towing BLACKBIRD to some obscure body of water many miles from home and camping in her during rest stops along the road.

Belowdecks, BLACKBIRD serves up a cozy space for one or two adults. We’ll label the accommodations, which comprise a V-berth, enclosed head, and a galley opposite, luxurious camping. It certainly captivated me. BLACKBIRD and I met for the first time at a marina in Grand Isle, Vermont. I’d driven north from Connecticut to meet Bassett and spend an afternoon aboard the boat. Arriving early, I went aboard and crept into the cabin like a jewel thief slipping into madame’s boudoir. Bolger has referred to the layout as “shipshape.” I have to call the ambience magical. I went forward, collapsed onto the V-berth, closed my eyes, and let the boat’s polite motion lull me to sleep. Her original owner cruised the shallow waters of south Florida and lived aboard for a number of months. Before that, he and Bassett took the boat from The WoodenBoat Show in Newport to Grand Isle via the Hudson River and Champlain Canal. In the tropics or during the summer months farther north, we’d spend more time outside than in, lounging on a beach chair in the cockpit, a large umbrella sheltering us from the sun. We’d cook on a portable grill, sip espresso that we made on the stove in the galley, and then toast the sunset with a snifter of fine brandy.

In keeping with the theme of carefree mobility, Bassett specified outboard power for BLACKBIRD—originally a 50-hp Mercury. So equipped, the boat is easier to launch and retrieve, is lighter in weight, and doesn’t require all the plumbing and through-hull fittings that an inboard does. Installing an outboard also is orders of magnitude less intimidating to an amateur builder. Mounted in a watertight well, the motor doesn’t intrude on our peace as we cruise up the river, nor does it interfere with our appreciation of BLACKBIRD’s simple beauty.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzRequiring only moderate power, the 23′ 4″ hull efficiently slides through the clear water of Eggemoggin Reach near Brooklin, Maine.

Devoid of styling gimmicks, BLACKBIRD combines the purposeful look of a workboat with the grace of a gentleman’s launch. Although a cynic could argue that the complex shapes, especially in the trunk cabin, are hard to build and unnecessary to the boat’s function, she’d lose a lot of her emotional appeal if those shapes were eliminated—at least the love-at-first-sight part. The smitten enthusiast, emotions aside, could argue that the soft shapes allow the wind to flow more easily over the structure. He’d be correct. We’re not concerned with the aerodynamics of high-speed racing boats, but we are concerned with how the strong surface winds affect the boat’s directional stability in open waters and her maneuverability under slow way in close quarters. Rounded surfaces are slipperier than are flat ones.

The same idea applies to shapes below the waterline. BLACKBIRD’s barely plumb stem caps a sharp entry, which shows some hollow in the waterlines through station No. 2. Beyond station No. 2, the hull swells out, losing deadrise and gaining buoyancy as we trace the waterlines toward the transom. The run is flat, and the deadrise diminishes to zero degrees at the transom. Bolger worked magic in the flow lines, because the boat runs cleanly at all speeds, doesn’t need spray rails, doesn’t require more than 50 hp for a satisfying top speed (about 18 knots), and doesn’t roll enough to notice. Her light weight and flat run quicken the motion, but not uncomfortably so, as I discovered during a breezy day on Lake Champlain and in seas of about 2′.

Under way, BLACKBIRD happily slips along at any speed you select. At displacement speeds, her sharp entry splits the waves, letting her buoyant midsection ride gently over the remainder. She lifts to maximum speed in a deliberate rush, as though hurrying were beneath her dignity. At top speed, she carries her chin about 18″ above the surface of the water, waiting to engage the crest of another boat’s wake or a roguishly large wave that sneaked into the train. BLACKBIRD tracks well upwind and down but, like any lightweight boat, wanders a bit as she spars with the waves. Beam seas and wind nudge her this way and that, but not alarmingly so.

A fairly long skeg helps BLACKBIRD with her directional stability, in a straight line and in turns, but it limits the radius at which she takes a turn at the higher speeds in her range. The skeg robs the propeller of solid water; the engine revs, the boat slows, and the helmsman feels silly. BLACKBIRD isn’t a hot rod and should be treated accordingly.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzBLACKBIRD combines timeless design with modern cold-molded wood-epoxy construction. She looks fine even when standing still and should never leak a drop.

Bassett cold-molded BLACKBIRD of 1⁄8″ Western red cedar, the first three courses laid diagonally and the last longitudinally. He used Philippine mahogany for the keel, Honduras mahogany for the skeg, and ash for the stem. The method is well within the ability of amateur builders, and it produces a strong, stiff, and lightweight structure. Spiling—fitting the thin planks so they butt one another without gaps—and stapling to hold them in place while the epoxy resin sets require a great deal of patience. The bare hull, as Bassett and a handful of helpers lifted it off the molds, weighed about 500 lbs. The complete boat displaces 2,800 lbs.

Building the trunk cabin and windscreen taxes the craftsman’s eye and skills more than any other part of the boat. Bassett referred to the process as an exercise in free-form construction. The cabin’s delectable oval-shaped fascia rakes slightly aft, and its sides become perpendicular as they curve toward the cockpit. The coach roof slopes toward the bow and shows diminishing camber from the windscreen forward. Working in a relatively confined area, Bassett couldn’t get far enough away to really see the shape he was creating. “We would just put in a piece of wood and bend it until it looked like what we wanted,” he said.

Coaxing the many individual elements of a design into an engaging whole is the brass ring of design and construction. In BLACKBIRD’s case, the color scheme, working with the small riot of shapes, unifies the boat. “One thing becomes another,” Bassett said. “When you look at it, when you move around in it, when you steer it, you’re not just in a certain area—you’re in a whole boat.”

To meet BLACKBIRD is to love her, the way that strangers meet and, feeling as though they’ve known one another all their lives, stay friends forever.

Ken Bassett conceived the vision for BLACKBIRD based upon earlier work of Al Mason. Phil Bolger gave form to the idea on his drawing table, and Bassett brought the boat to life in his Vermont boatshop. The result: a truly classic design.

For plans contact:

Susanne Altenburger

Phil Bolger & Friends Inc.

66 Atlantic Street

Gloucester, MA 01930-1627 USA

(Contact information updated March 2022)

Ken Bassett retired and closed Onion River Boatworks in 2017.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Is this boat for sale?

A beautiful and practical craft, suited to the waters in which she is used, and looks magnificent from every angle.

If some skilled boat builder is interested in building one, I could be interested in purchasing one!

Beautiful boat and easily one that can be hauled anywhere, launched to start exploring coves and waterways. Fast enough to get one from point A to B for an evening nightcap looking at a sunset from the stern or sitting on a beach one claimed as their own. Well done by individuals who understand the peace, joy and pride a boat can give its owner.

Classic boat, a boat we all could treasure.

Eloquently presented and built.

This boat deserves to be built out

again and again

Please have someone contact me who can build it for me.