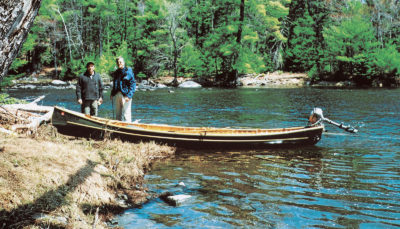

I’ve been the subject of a helluva lot of flattery over the past three days—not to say that I don’t appreciate it,” said Jim Hulm, beaming, while working his fantail launch alongside a floating dock at Connecticut’s Mystic Seaport. It was a Sunday in June, the third day of the 2007 WoodenBoat Show, and Hulm’s 26-footer, JOLENA III, had created a buzz among spectators. Its power plant, on the other hand, had created hardly any buzz at all.

Hulm, an Englishman living in New Hampshire, had built the boat a few years before to a modified design by Iain Oughtred—who had developed the plans for a client in England. The original was 30′ long, and had a cabin and head and other accoutrement. Hulm shortened the distance between the construction molds, creating a hull 4′ shorter than the original boat. “Iain was quite excited about that,” he said of the modification, “because it would give more spring to the sheer—which it does.” The shorter boat has no cabin. It’s an open day launch.

Photo by Matthew P. Murphy

Photo by Matthew P. MurphyJOLENA III is an adaptation of an Iain Oughtred design. She is inspired by the steam powered Thames River launches that came into vogue in England in the 1860s, but her propulsion system and construction are thoroughly modern.

The builder changed the propulsion, too. The 30-footer was launched with “a big old gas engine about amidships”—though designer Oughtred reports that the original boat is now electric powered. Hulm’s 26-footer, on the other hand, has had an EVA Advanced Electric motor since its launching. “EVA [Electric Vehicles of America] is a small company that set out to provide vehicle conversions — for deliver y vans and the like.” Hulm chose a 36-volt motor, though it will withstand the 48 volts of his battery bank. The battery bank is composed of eight 6-volt golf-cart batteries. The motor is coupled to the propeller shaft by a timing belt running at a 5:1 reduction ratio and turning a 20 x 19 three-bladed bronze wheel. “Dave Gerr’s book, The Propeller Handbook, was my bible when I was putting this together,” said Hulm.

What does this machinery translate to? The motor puts out about 5 hp and the boat will travel 20 miles on a single charge. Hulm said that “people often ask, ‘What if you slow down? Do you get better mileage?’ The answer is no; it’s still 20 miles [on a single charge],” regardless of speed. “While it’s true that the power needed to move a displacement hull drops off dramatically at lower speeds,” he said, “the electrical efficiency of the motor also drops at lower RPM. Running at 5 mph for 4 hours puts the same demand on the batteries as 2 mph for 10 hours.”

This is the first boat Jim Hulm has built from scratch. His previous experience included the construction of a Glen-L 14 kit sailboat and the restoration of a Turnabout. He then restored an 1890s fantail launch. “I restored that and put it in a museum,” he said, “and then I got to this.”

Richard M. Mitchell, in his book The Steam Launch (International Marine, 1982), gives an excellent history of steam launches. He notes the year 1860 as “a convenient peg” after which steam power in small boats became possible. “They [the boats] grew lighter, trimmer, thriftier, and more numerous, and as their marketability increased, competent builders began to produce a few, at the same time making further refinements.”

One of the principal refinements of this era was the development of the elliptical, overhanging stern— the so-called “fantail.” This stern configuration allows a narrow, fine-lined shape like a steam yacht to swing a big, slow-turning propeller. The stern, Mitchell notes, is “only incidentally beautiful.” Some might say it is downright seductive, for that stern shape has outlived the power-plant technology that gave it life.

Steam launches developed on the Thames in response to the demand for livery boats. There is a long tradition in London of fluvial courtships, and thus a tradition of oar-powered pleasure boats. “Commercial steam launches,” writes Mitchell, “evolved out of rowed boats and small working steamers and were shaped not by custom but by determined efforts to make money with engines in boats.” Between 1868 and 1875, one builder, Yarrow, had built 350 launches “at first for gentlemen and their ladies along the Thames, later to be used as ship’s boats on oceangoing vessels.”

Photos by Matthew P. Murphy

Photos by Matthew P. MurphyJim Hulm (at helm) installed in JOLENA III a motor devised for electric delivery vans. The timing-belt drive provides a reduction ratio of 5:1.

One of the beauties (depending on your bias) of power-boating on the Thames is its strict speed limit. It varies between 4 and 8 knots, so there is no pressure to develop faster, resource-guzzling boats. An outing under power remains, essentially, a motorboat excursion at rowing speeds. In fact, there is a unique craft there—a cousin to the early fantail launch—that appears fast in profile, with its sloping stern (almost a reverse counter) and rakish windshield. Its speed, however, is restricted to the low legal maximum.

JOLENA III, said Iain Oughtred, “is a fairly typical Thames River launch.” Her predecessor was designed “for a guy from Egypt who wanted an impressive-looking launch,” and was built of glued lapstrake plywood. In addition to tweaking the original’s dimensions and power plant in the creation of JOLENA III, Jim Hulm changed the construction. He built his boat of 3⁄8″ strip planks covered with two diagonally opposed layers of cedar veneer, creating a smooth-skinned hull more in keeping with the early carvel-planked launches. The hull is covered inside and out with 10-oz fiberglass cloth, with an additional layer of 4-oz Dynel cloth on the outside. Jim Hulm accomplished much of the modification on his own, in conversation with designer Oughtred. Strip planking, said Oughtred, “is just not a type of construction that interests me.” Oughtred is known mostly for his exquisite small sailing craft, and glued plywood is his construction method of choice.

People interested in owning a boat such as JOLENA III, but not interested in building, would do well to speak with the folks at Elco. They manufacture a line of fiberglass fantail launches, and also sell complete drive systems. Their power plants range from below 2 hp to 8 hp, and there’s a hybrid arrangement (think Prius), as well. These systems would be of interest to readers wanting to build a boat, but not wanting to engineer the mechanicals from scratch, as Jim Hulm did. Other fantail launch plans are available, too. Phil Bolger has drawn an exceptionally pretty one (a 23-footer whose plans are available from The WoodenBoat Store, ). JOLENA III has a varnished deck, seats, and console—and plenty of other brightwork, too. This will raise maintenance concerns for some readers. Here’s what Jim Hulm has to say about that: “I haven’t put a lick of varnish on it in five years.” The boat’s brightwork is in fine shape—a testament to the benefits of thoughtful storage. He keeps the boat under cover when it’s not in use. “People talk about the high cost of maintaining a wooden boat,” said Hulm, but he has demonstrated that the cost can be reasonable “if you keep it [the boat] in the right environment.”

At the helm of JOLENA III, Jim Hulm is a happy man. During our brief excursion on the Mystic River, he reduced the satisfaction of building his boat to these three things: “First,” he said, “it’s the satisfaction of building something with your hands; second, it’s the intellectual challenge of laying out the interior; and third, it’s the artistic challenge of creating something that just plain looks nice.” Uncounted builders worldwide owe a debt to Iain Oughtred for giving them a leg up on point number three.

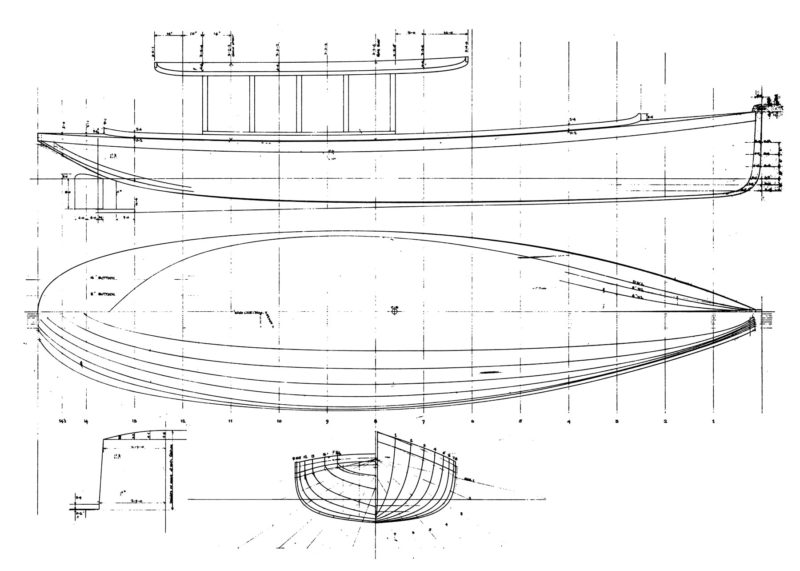

JOLENA III was built to the modified lines of this 30-footer that Iain Oughtred designed for a customer in England. Jim Hulm reduced the station spacing for his boat, creating a 26-footer.

As of November 2022, Plans for the 30′ version of JOLENA III do not appear on Ian Oughtred’s website. The review appears here as archival material.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I live on the Thames in England and have a boat almost identical to JOLENA. This article explains the situation perfectly: the speed limit is 4 knots where we are and this is perfect for a little cruise with a bottle of wine in the summer. My boat is called GEM and was built in about 1926 and is of carvel construction. I converted mine to electric some years ago and find that the batteries need to be replaced every 5 years or so, when the cruising distance drops off a cliff.

I sensed immediately the Mystic River area in the photo, delightful as is the beautiful JOLENA III.

Question: Why the round bottom (other than beauty)? Any benefits from a flat bottom given same propulsion set-up?

Please share your speed vs power curve: knots per kw.

Please share your speed vs power data on your beautiful launch.