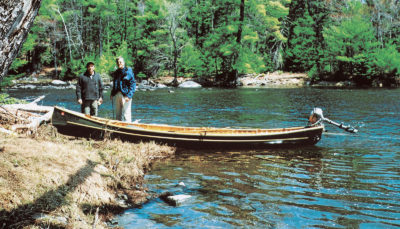

There’s something nearly archetypal about the Long Point skiff. This 15-footer has high sides and a flat bottom, and is driven by a small four-stroke outboard motor. “It used to be that everyone had one of these things,” said the designer, Tom Hill, as we skipped across a modest chop on Penobscot Bay in mid-August. “They ranged from Maine to the Chesapeake, and were called clamming or crabbing skiffs.”

Hill conceived his own version of such a skiff for fishing the waters around Provincetown, Massachusetts. He’d made frequent outings in an earlier, lighter skiff of his design. One day he found himself towing a big fish alongside that boat. The big fish attracted a school of sharks. The small skiff’s topsides were only 4mm thick, and the sharks were bumping the hull. That set Tom Hill to thinking about bigger boats. “To make a long story short,” he said, “we decided we needed a larger boat with higher sides.” (Hill all but defined lightweight boatbuilding in the 1980s. The cover of his book, Ultralight Boatbuilding, pictures him holding aloft a double-paddle canoe on the tips of the fingers of his right hand.)

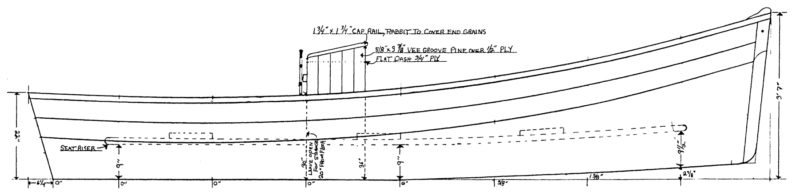

Here’s how Hill describes the Long Point’s design brief on his web site: “I wanted a flat bottom skiff that would draw a minimum amount of water to allow us to negotiate the Pamet Harbor at low tide and also be good for fishing the flats and marshes. She also needed to be deep and have a high bow for trips offshore, 15 miles from home.”

Photo by Howard Mitchell

Photo by Howard MitchellTom Hill’s Long Point skiff is a robust derivative of once-ubiquitous working craft. With a flat, narrow bottom, she is both fast and efficient.

The designer-builder bought a used 15-hp Honda longshaft. “I couldn’t afford it, but Barbara [his partner] said she’d pay for the motor if I’d build a new boat. I knew I wanted a flat-bottomed boat because I wanted to go as fast as possible” with that minimal power, said Hill. Thus inspired, Hill made his first sketch of the boat in about 15 minutes. “Once I got the profile down, I wanted to keep the bottom as narrow as possible. And I wanted plenty of flare to keep it comfortable and dry. I then decided that I should change it—which is a mistake I often make.” He tweaked the lines and poked and prodded, but ultimately reverted back to the shape he’d developed in those first 15 minutes.

The skiff’s 11⁄2″ bottom is heavy and robust, and it feels like a sidewalk underfoot—especially in the choppy waters that are often the bane of flat-bottomed boats. The Long Point originally had a 3 ⁄ 4″ bottom. “I felt some oil-canning [deflection],” said Hill of his early trials in the boat. With that, he hauled the boat, removed the console, turned over the hull, and added another layer of 3⁄4″ plywood. He added a layer of 20-oz biaxial fiberglass cloth to this, making for a bullet—or beach—proof bottom.

“I wanted to be able to beach it,” said Hill. “We often beach for lunch. That’s another beauty of flat-bottomed boats: they beach bolt-upright.” The other beauties are speed and stability. The skiff’s ultra-heavy bottom acts as ballast. “You can step aboard standing on the rail,” said Hill.

Flat-bottomed boats are efficient, too. “I’m hard-pressed to use three gallons all day,” said Hill of a typical fishing expedition. He estimates that, with the throttle wide open, the 15-hp Honda on the Long Point skiff will burn one gallon per hour, with the boat (with just the driver) running at 20 knots. The highest speed Hill has recorded in the Long Point is 24.5 mph.

Photo by Howard Mitchell

Photo by Howard MitchellThe Long Point was designed around her motor, an economical 15-hp four-stroke outboard. More power would be overkill on this boat.

The simplicity, fuel economy, and “beachability” of flat-bottomed boats comes at a cost. There’s no way around it: Such a hull pounds in a chop. But one Long Point builder reports that there is a way to sidestep this pounding— literally: Stand to one side of the console, heeling the boat a bit while under way. This presents the “V” shape of the chine, rather than the pan-flat bottom, to the waves, smoothing the ride a bit. The prudent operator, however, will also slow down in a chop, improving the comfort of the crew.

The topsides are of glued lapstrake plywood. The garboards (lowest planks) are quite wide, suggesting that the hull would come together quickly. Construction is fairly conventional. It begins with a ladder-frame strongback that’s set right on the shop floor, and molds and profiles (describing the stem and stern) are erected on this. Ribbands are bent around the molds to describe the planks, and the planking stock is hung on the boat and scribed directly from the inside; there’s no laborious transferring of offsets involved in getting the plank shapes. When the boat is planked, the chines and garboards are beveled to accept the 1 1⁄ 2″ of bottom planking, and then the bottom is fiberglassed as described above.

Photos by Matthew P. Murphy

Photos by Matthew P. MurphyThe Long Point skiff’s layout is simple and functional. A bucket (a Coast Guard requirement) does double-duty as an anchor rode locker; the console (designer–builder Hill is at the helm) is built of V-match pine glued to a plywood backing.

Hill prefers to paint his boats while they’re still on their building jigs, and that’s what he does with the Long Point skiff. The boat is held rigid, for sanding, and it’s much easier to work on a bottom “downhanded,” rather than crawling underneath an upright boat and working overhead, like Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Painting a hull while it’s still on the jig, however, will require considerable restraint of a first-time builder. There’s a near-universal urge for beginning builders to get their hulls off the molds and see them freestanding.

The completed, partially finished hull is then removed from the building jig and flipped over for framing and fitting out. The frames are installed only on the topsides, to add stiffness; the bottom is sufficiently robust to do without them. Hill used white pine for the frames of the boat we tested. The wood is lightweight and holds fastenings well. “Every ounce you can save is one less you have to drive through the water,” he said. Fitting out follows, and includes quarter knees, breasthooks, seats, console, controls, engine, tanks, etc. Building time can vary considerably, depending on the skill and pace of the builder, and level of finish.

In addition to his reputation for balancing canoes on his fingertips, Hill is known for exquisite detailing. The Long Point skiff that we trialed—the original boat, at age 11—is painted in marine enamel and looks like it just rolled out of the shop.

Hill is equally detailed in his cost estimating, and is quite confident in what one should budget for materials to build a Long Point skiff. This includes 3⁄ 4″ sapele plywood for the bottom, four sheets of similar 1⁄ 2″ material for the sides, trailer, engine, 12 coats of paint (and its associated sandpaper), controls, fuel tanks, masking tape, anchor, cushions, VHF radio, and compass. The figure is $13,000. Hill acknowledges that builders have reported substantially lower building costs, but he said that his calculation includes the finest materials and all bronze fittings and fastenings. And he questions whether those lower figures include things like masking tape and sandpaper—small items that can quietly add up.

As of the day we tested the boat, Hill had sold 123 sets of plans for the Long Point skiff. He’d sent them to all sorts of builders, but noted that the design was particularly popular with commercial fishermen, who use their skiffs as bait tenders and the like. One pair of New York City tugboat operators built one on the deck of a tug. Indeed, it’s a hardy-looking little hull, one right at home alongside its working forebears. “One of the great things,” said Hill of his experience with the design, “is the response you get from commercial boats.”

It’s been said that every boat is a compromise among speed, comfort, and efficiency. Tom Hill seems to have hit an ideal balancing point with the Long Point skiff. The boat fits her niche. “In my mind it’s perfect,” said Hill, “and I’ve had it for 11 years.”

Wide garboards and only two additional planks suggest that the hull would come together quickly. Careful attention to detail will make the boat stand out.

Plans for the Long Point Skiff are available from Tom Hill Boat Designs for $75.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I built a Long Point about 18 years ago, as quick and dirty as could be done, using exterior plywood and house paint. The plan was to run it around Plum Island Sound for oystering and getting to sandbars for fishing, then let it fall apart when I finished a cruising sailboat. Eighteen years later, my grandson is still scooting around Great Bay in New Hampshire in the boat, now with a center console so you can see over the bow. Great boat. Simple as can be yet classic workboat looks. Wonderful design.

The flat-bottomed skiff is a badly underrated type. In the right environment it can give one more value and more fun for the money than almost any other type of boat. When I was a boy in the 1950s, Narragansett Bay was full of outboard-powered “quahog” skiffs. The Long Point Skiff is a beautiful and more modern example of the type.

In my 60s, when I had time to build a boat, I chose Chesapeake Light Craft’s Peeler Skiff kit (http://cumulus.aunt-mary.net/images/peeler/), another flat-bottomed skiff using modern materials and one of today’s light and efficient outboard motors. Five years later, it has become a much-used family boat moored in Wickford’s Fishing Cove behind our daughter’s home. We use it for fishing on Narragansett Bay, picnicking, and just messing about. It’s been the smallest boat I’ve owned – and the most fun. Great work, Tom Hill!

From my research, and experience, there is no “garboard plank” on a hard-chine hull. I’ve always heard it described as the “chine plank”; maybe I’m wrong.

This is the boat I’ve been looking to build. It fits everything I’ve been looking for. I’m having trouble finding a source for the plans. I hope this comment could get to Tom Hill. It seems like maybe he has shut down his website. Any help would be greatly appreciated.

Karl

Can the hull be lengthened?

Thank you for this spotlight. This boat fills the exact niche that I am looking for as well.

Like a previous poster, unable to make contact with the designer to buy a set of plans at this time though.

I’ve been looking high and low for a Casco Bay striper boat, student lobster boat, Maine Island Trail boat. Lots of good designs, but most are over/under built for our current needs. This one (or a Tollman skiff) seem to be right on the money!

I like the lines, and really like the clean cockpit sole w/no traverse frames inside to trip on/gather crud. At 15′, how much does she weigh?

As of today, it appears that Tom Hill’s website (http://tomhillboatplans.com/) is up and plans are available.

Hallo Tom,

I am a boatbuilder from Norvay, I am building a Long Point Skiff, not in plywood, but in Norwegian pine and with teak transom and the front stem, the frames are made from teak also from old teak doors and windows.

All the teak materials are from doors and windows.

I am nearly ready with her and in a short time will put her into the water.

Some input from Norvay