A year ago I reviewed the Fine, a fast sliding-seat rower from Oyster Bay Boats, a shop in Madeira Park, British Columbia, run by Rick Crook, designer and boatbuilder. I was impressed by the boat and pleasantly surprised that I could row it even after I’d intentionally swamped it. In the past year Rick developed another fast rower, the Salish, a coastal rowboat that can’t be swamped. Rick described the Fine in his website as a “full-body workout machine…wider than a rowing scull, thus more stable, and suitable for ocean rowing, in reasonable conditions.” About the Salish he wrote: “Salish is built for enjoying and exploring coastal waters. She is self-bailing, and by virtue of this, will handle conditions that open boats like Fine may not.”

Christopher Cunningham

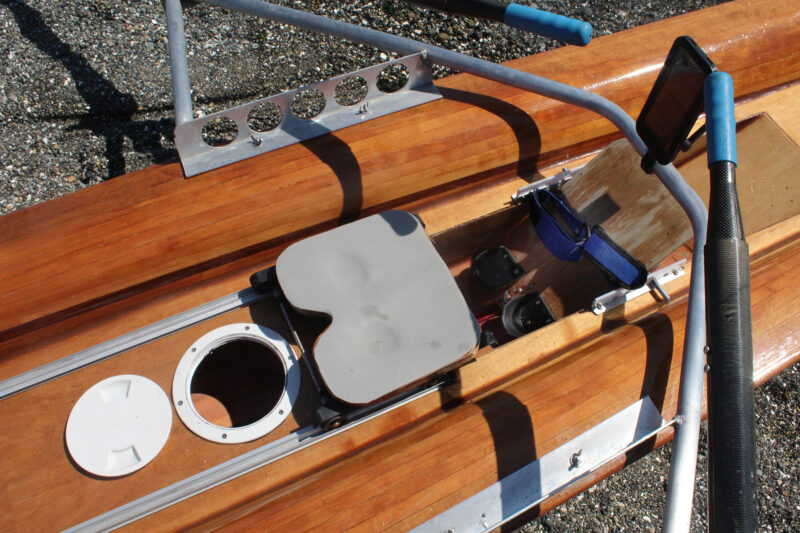

Christopher CunninghamA gasketed hatch in the foredeck provides access to the voluminous forward compartment, which is one of four watertight flotation chambers.

Like all Oyster Bay Boats, the Salish is strip-built with cedar, and sheathed inside and out with ’glass and bio-based epoxy. The deck has inconspicuous specks where staples once held the strips to the molds. The boat is finished bright, and the cedar has an appealing warm glow, but the finish isn’t brought to the high shine of strip-built boats that span the gap between boatbuilding and art. The Salish is meant to be used and accumulate the scars of adventurous service without tormenting the rower.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe rowing station has a flotation compartment under the sliding-seat deck. A plastic port provides access.

Rick weighed the Salish seen here and it came in at 69 lbs. He saved some weight by using cedar strips that were 3⁄16″ thick, thinner than the 1⁄4″ strips he usually uses, but they made building more difficult. Subsequent builds using 1⁄4″ strips would come in a bit heavier, perhaps 72 lbs. That’s more than I’d be able to lift safely all at once onto a set of roof racks. The outrigger is easily removed by spinning the wingnuts off the four bolts that secure it to the deck, but lifting the boat from its middle would be virtually impossible because there are no handholds there. To load the Salish to a cartop without help would require lifting one end at a time. I’m able to do that with my 18′ 9″ decked lapstrake canoe, which weighs about 80 lbs.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe stretcher sits in a footwell that limits how much water can get aboard without flowing out through the open transom. The sloped aft well allows water to flow up and out when the boat surges forward when rowed at speed.

Getting aboard a speedy sliding-seat boat can be awkward, especially if you must step between the tacks/slides on an elevated deck and rely on your oars to stay upright until you get seated. The Salish has excellent stability, better than I had anticipated, and Rick pointed out that there was no need for the boarding method I had been accustomed to. I could just let go of the oars, turn my backside to the boat, and sit down on the side deck. The boat would support me while I lifted my legs aboard and planted my feet at the stretcher.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe bottom of the open transom rides right at the water level. The fitting on the port side is a vent and drain for the stern’s flotation chamber.

The rigging geometry was a good fit for my 6′ frame. During the drive, the handles traveled at a comfortable and effective level that was level with the bottom of my sternum. At the recovery, the handles were high enough that they wouldn’t hit the tops of my legs if the boat were rolling when the waves kicked up. The outriggers felt very firm and didn’t flex or creak, even when I pulled my hardest. The stretcher has a plywood footboard equipped with plastic heel cups and Velcro straps. It’s set at a comfortable angle and offers a solid surface to push against and its position is adjustable. The seat has a double-acting carriage rather than ball-bearing wheels and rides on aluminum tracks. It’s a system commonly used in racing shells and is smooth and reliable.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe Salish has surprisingly good secondary stability for its 34” beam. I could very comfortably and safely sit on one side.

For my speed trials, on flat water with no wind, at a relaxed pace the boat held a steady 5 knots. At a sustainable aerobic level of effort, the Salish did 5.7 knots. In short-all-out sprints, the reading on the GPS fluctuated a good deal as the hull sped up while I moved sternward on the recovery and slowed down as I moved toward the bow during the drive. The average speed in between was about 7 knots, a satisfying clip, made especially exciting because the boat trailed a little rooster tail in its wake.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamAt the catch, when the weight of the rower (here designer/builder Rick Crook) is well aft, the transom remains right at the water level.

The Salish tracked very well, due, I expect, to the skeg and the long waterline. Pivoting the boat through 360 degrees took 10 strokes, pulling first with one oar then backing with the other. It was easy to maneuver. On one of my speed runs, a stand-up paddler surprised me by paddling across my line of travel just as I was drawing near. I had been checking over my shoulder at the water ahead and saw the paddler just in time to slam the blades into the water with the starboard oar especially deep to veer away. I was able to stop the Salish with just a kiss of its bow on the paddleboard. The paddler remained standing.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamAt the finish, the bow has enough volume to keep the rower’s weight, shifted forward, from settling noticeably deeper in the water. The Salish maintains good trim throughout the stroke.

I rowed backward to see how the open stern would behave. A normal slow speed I’d usually use for maneuvering didn’t do much so I applied more power and used the full slide to get my weight as far aft as I could at the end of the stroke. That pushed the transom into the water and, as I kept rowing, I was able to get water to flow up to the footwell and even to the deck under the sliding seat. The boat didn’t feel at all unstable with all that water aboard and the sliding seat kept me high enough that my pants didn’t get wet.

Christopher Cunningham

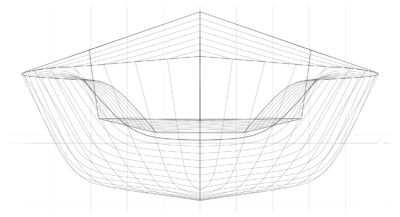

Christopher CunninghamThe Salish’s broad foredeck is the result of the flare in the hull’s forward sections. The flare provides secondary stability when the boat is heeled, and lift while rowing into waves.

I only had a few boat wakes to row through so couldn’t get a sense for the Salish’s rough-water ability, but I’d expect that the hull would provide reassuring stability. The flare forward would send spray outward and any water that came over the foredeck would soon make its way through the cockpit and footwell and drain out the stern. The closed-deck Salish can’t be swamped. Its ability to support my full weight seated on the side deck is a good indication that a rower would fall out of the boat before it capsized and be able to crawl back aboard without having to rely on the oars to provide stability. (Rick experimented with a self rescue over the stern and documented it with a video.)

Todd Dickens

Todd DickensI rowed stern-first at a brisk pace to see how much water would come aboard. While I flooded the footwell, the Salish suffered no ill effects, and its stability wasn’t diminished by the weight of the water.

Todd Dickens

Todd DickensA couple of strong forward strokes forced almost all of the water out of the footwell and onto the aft deck to flow out.

If the Salish is indeed “built for enjoying and exploring coastal waters,” it should be capable of carrying enough gear to make multi-day cruises in comfort. There is sufficient volume enclosed by the deck and hull to contain much more gear than a well-equipped backpacker can carry and the only impediment in the Salish I rowed is the lack of access to the potential protected storage areas. The hatch on the foredeck would work well for day excursions, but the opening is only just wide enough for a sleeping bag and any gear pushed forward into the bow would be out of reach without a tether. Since the boats are built to order, having a larger hatch would better suit a Salish intended for cruising. The Salish shown on the company’s website shows a round plastic hatch on the recessed aft deck. There wouldn’t be as much storage space there, but it would be a good place for heavier items such as water, tent poles, and cookware that could balance the bulkier but lighter items in the bow and maintain the boat’s proper fore-and-aft trim.

The Salish has the stability to give a novice a good introduction to sliding seat rowing, the full-body exercise a fitness buff craves, the speed to satisfy an experienced recreational rower, and the seaworthiness to take an adventurer on explorations of coastal waters.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats.

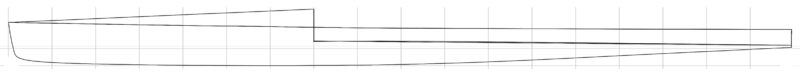

Salish Particulars

Length: 18′

Beam: 34″

Draft: 4.7″

The Salish is built to order by Oyster Bay Boats for $6,800CAD. The price includes carbon-fiber composite oars.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Very interesting boat! The self rescuing and possible storage make it extra interesting for adventure racing maybe too. I could not heave it around myself but there are little wheeled dollies maybe for one end to get it on a car rack. For portages, starts to get a lot of junk to pack.

Very good review! I got caught up in the boat as the review brought me there.

Hi Chris,

I move Salish around with a kayak dolly. If I need to manhandle it around for short distances, it balances pretty well at the hatch under the seat. I can take the hatch cover off, and pad the edge of the opening with a rag and carry it on one hip. That is not suitable for a portage, but fine to carry it down a ramp or over the seawall.

Best Regards,

Rick

Interesting minimalist seat/rigger setup.

The vertical rearview mirror is intriguing but did you find the field of vision wide enough?

Are the seat tracks adjustable fore and aft?

As for seaworthiness, what qualifies as reasonable conditions?

The device clipped to the middle of eh outrigger is a smartphone with a GPS app for speed data.

The tracks are fixed. Only the stretchers are adjustable.

Rick mentioned “reasonable” in reference to the Fine rather than the Salish. I think it makes good sense to leave it to the rower to determine what is reasonable, as the rower’s skill, strength, and judgement are as important as the boat’s potential.

Very pretty boat, I would love to see a comparison between this, the CLC Expedition Wherry, and the Angus Expedition Rowboat. I think it would make for quite a test to see how all three stack up against one another.