Pygmy Boats

Pygmy BoatsThe Wineglass Wherry, a plywood pulling boat, takes its inspiration from the beach-launched working craft of Seabright, New Jersey, and Penobscot Bay, Maine.

Paddling for long stretches of time has never been my thing. I like the convenience of my kayak perched atop the car or near the water, ready to go at a moment’s notice. Likewise, I have fond memories of kayaking expeditions to Maine islands, with all of my essentials tucked away in dry bags and stowed neatly under decks. When paddling for over an hour, however, I invariably find myself craving more leg space, or shifting my weight to restore restricted blood flow. I also find myself craving cookies, and want to dig out one of those dry bags while underway, to get to the Mint Milanos stuffed in beneath my polar fleece.

Avid paddlers, please do not take offense at this admission; it’s my shortcoming, not yours or your sport’s. You who are more sophisticated kayak folk than I might chafe at my chafing, and might suggest that I pack the cookies more thoughtfully, within arm’s reach in the cockpit. Fair enough. But still the fact remains: While paddling my kayak for long periods, I always find myself asking why I am not rowing instead.

And so I’ve been curious for years to test the Wineglass Wherry from Pygmy Boat Co. of Port Townsend, Washington. Pygmy is highly regarded for its beautiful and beautifully precise plywood kayak kits. Its boats are built by the stitch-and-glue method, whereby panels are literally sewn together with copper wire, the resulting seams then reinforced with fiberglass tape set in epoxy. By following the directions carefully, anyone can build a Pygmy kit. The resulting kayak will rival or exceed what you can buy off the shelf—in terms of both weight and performance. And you’ll have built it yourself.

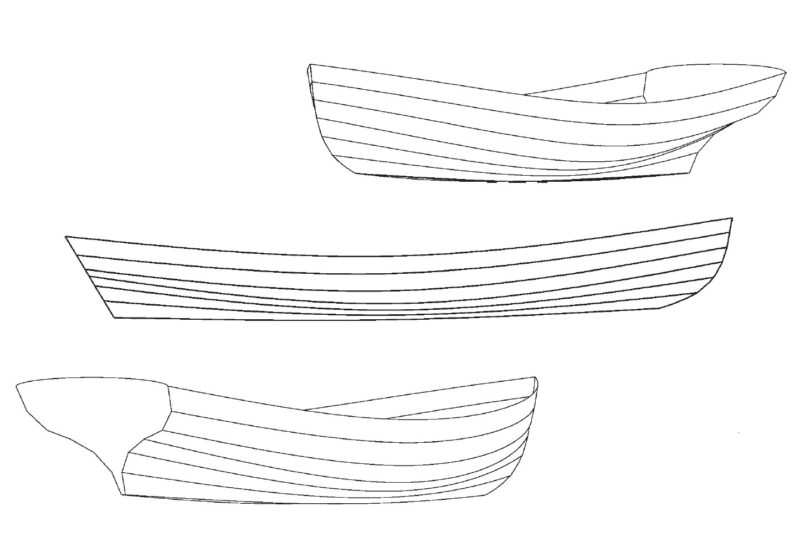

In designing the Wineglass Wherry, Pygmy’s founder, John Lockwood, used the same construction techniques as those of his kayaks. But in developing the boat’s shape, he looked back in time to salmon wherries from Maine’s Penobscot Bay and blended their features with New Jersey’s Seabright skiffs. The signature Seabright feature is the so-called box garboard. Study the photo at the top of the next page. See how the boat’s bottom is narrow and flat in the after regions, and is bordered by the two lowest planks—the garboards? That’s what I’m talking about. This feature allows the boat to stand bolt upright on the beach, and it provides a handy sump for bilgewater. The boat’s topside profile, meanwhile, bespeaks its Maine genes.

Pygmy’s headquarters are located within the grounds of the annual Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival. So, on Sunday during the 2008 show, I disappeared from the booth for a few morning hours and took a Wineglass Wherry for a spin. Here are some impressions.

Pygmy Boats

Pygmy BoatsBox garboards form the hollow keel seen here in the boat’s stern, which serves as a narrow sump for bilgewater. They also allow the boat to sit upright on the beach.

The Wineglass Wherry transports effortlessly over-land on a two-wheel dolly. Balancing its 90 lbs over the wheels, I was able to push the boat along the blacktop, down the ramp, and into the water alone, without any strain. With oars in position, I navigated the slalom of rafted boats and made my way out into calm Port Townsend Bay. The boat was reassuringly stable. With its double-ended waterline, it carried well between strokes with clean water astern and, despite its light weight, the motion in waves was not corky.

The wind built to about 12 knots during my outing, and I set courses at various relative angles. The boat was well mannered on all points of sail, tracking dead straight. This was especially impressive on a beam reach, when one might expect the boat to round up, or “weathercock.” There was none of this behavior. (Of course, I use the phrase “points of sail” figuratively. The boat has no rig, and Pygmy’s Dave Grimmer cautioned that it’s too tender for such use. “It’s essentially a pulling boat,” he said.)

The Wineglass Wherry has been a popular seller for Pygmy. Grimmer tells me that over 1,000 of the boats have been built. At least one of those was for designer Lockwood himself who, with his wife and daughter, made a four-week, 206-mile trip in 1995. The family explored numerous lakes, rivers, and creeks on the trip, and portaged between these waterways on flat trails using a two-wheeled dolly. They carried 150 lbs of gear, and report that they passed every canoe they encountered. Note that it’s the boat’s plywood construction that makes such an expedition possible. Were this boat traditionally built, with bent hardwood frames and cedar planking, it might weigh as much as 250 lbs. It would be a delight to row, still, but two people of average build could not easily lift it from the water and onto a dolly and wheel it down a narrow woods trail.

One of the joys of building your own boat is the ability to fit it out to your own requirements. My test boat in Port Townsend was a dedicated demo unit, and clearly it had seen some miles. A critique of its details would, therefore, be patently unfair. But the blank slate of this boat did give me ideas of how I might fit out my own, were I to build one.

The first thing I’d add would be a sculling notch, for the sake of versatility in tight spaces, and to allow an elegant recovery in the event of a dropped oar. The second thing I’d do would be to paint the interior, rather than leave it bright. As with my opening rant about long kayak trips, that’s just me. I prefer large expanses to be painted, and for bright surfaces to be reserved for accents and contrast. And, finally, I’d add some subtle detailing to the knees and breasthook—perhaps undercut them a little bit, for visual refinement. The ability to add such personal touches is what makes building your own boat so rewarding.

Michael Berman

Michael BermanThe Wineglass Wherry, at 90 lbs, is easily transported and beach-launched for day outings. It has also proven itself as a camp-cruiser; its designer, John Lockwood, built his own example of the design and made a month-long expedition in it—with his family, no less—in 1995.

If you’ve built a stitch-and-glue kayak, then you already know how to build a Wineglass Wherry. You won’t need a strongback or forms; the panels are simply sewn together right on the shop floor, quickly yielding the shape of a boat. It seems to me that this boat would be a logical next step for a kayak builder. I said so to Dave Grimmer, and he told me that it’s actually worked out both ways: kayak builders have indeed gone on to build Wineglass Wherries, but just as many Wherry builders have gone on the build kayaks. Go figure.

This boat turns heads. A sailboat motored by during my test on Port Townsend Bay. “Nice boat,” shouted the skipper as he passed abeam. “Did you build it?”

“No,” I admitted. “Just borrowing it.”

You, however, with a little time and effort, could answer yes—and paint it any way you like.

Pygmy Boats recently closed its doors and no longer sells Wineglass Wherry kits.

Hi from Dorset, UK. I built a Phantom hi-performance single-handed, single-sailed racing dinghy by the stitch and glue method some 25 years ago now.

I can testify that if you follow the instructions properly it is remarkably straightforward.

In my case I visited the designer, purchased a rolled-up sheet of brown paper on which were drawn all the necessary outlines for each plank, and a typed up set of instructions, and was sent on my way! So I had the added challenge of cutting out each plank.

The result, some 8 months later, was a lovely, fun single hander for a 196-lbs ex-Royal Marine. I should add that by sticking firmly to the design outlines etc, when the boat was comprehensively measured for class racing she passed with flying colors too. I had just turned 60 at the time.

Sadly I rather think that getting a kit of the Wineglass Wherry from the US would be prohibitively expensive – however she would be absolutely what I would like as I downsize from a 26′ (plastic) sailing boat for pottering around the extensive and fascinating shores of my home port of Poole Harbour in Dorset. At the time of writing all the over-wintering birds from Scandinavia are just arriving – what a sight.

PS I thoroughly enjoy your magazine – and can but dream!

I built a Wineglass as my first stitch and glue project, and it was a lovely boat. Being a sailor, I felt the need for a sail rig, and put one together, but it never quite “took”. Does anyone produce kits to this design now that Pygmy has closed? If the kit were available, particularly if it were lap strake, I’d consider building another. Improvements in CNC cutting could make “lap stitch” construction possible and improve the panel joints from their earlier butt joint configurations. This was a very easy boat to build, and the results were just beautiful!

The email linking to this page refers to “the former Pygmy Boats, Inc.” Does the company still exist? Has it changed its name? Is the kit still available and, if so, from whom?

I built the wineglass wherry over 20 years ago in my basement as my first kit build. It goes together really well and is a delight to row.

I have wondered how builders fare when glassing lapstrake boats. Seems like it could be problematic, getting the glass to go around sharp corners and into the valleys between strakes. Are there tricks that make this work out okay?

Are there any plans available for the whineglass wherry, from South Africa?