I never met John Gardner, but I’ve spent many an afternoon with him. Leafing from one chapter of his books to another, it’s easy to get distracted by the down-to-earth practicality, the enthusiastic descriptions of traditional boats, and the ringing call to action to see these boats built anew and put to use. Just when you think you’ve got one picked out, you accidentally flip the page to another chapter, and your indecision is off on a new tack, evaluating the great Mystic Seaport historian’s solid reasoning on the virtues of yet another historic type.

Such must have been very much the way that Rick Hayden of China, Maine, spent an afternoon—or maybe many afternoons. Ultimately, he did what we all must do: he made a choice. The boat that suited his needs—the one that proved irresistible, the one he would see built— was the Moosabec Reach Boat, which occupies Chapter 3 of Gardner’s Wooden Boats to Build and Use (Mystic Seaport Museum, Connecticut, 1996).

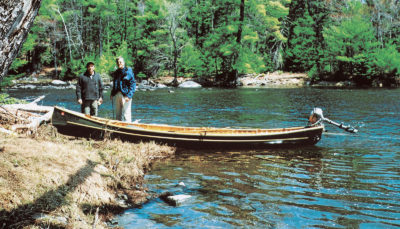

She’s a 14′ 3″ boat, with a 4′ 6″ beam, two rowing stations, and a handsome and practical two-masted sprit rig. Andy Chase of Castine, Maine, bought the original boat, which may have been built in the 19th century, in the 1970s. It was he who brought it to Gardner’s attention. Chase also documented the hull during a work-study program at Mystic Seaport while still a high school student. Originally used for lobstering and fishing on Moosabec Reach near Jonesport, Maine, such boats followed the demands and needs of their owners and builders, rowing easily to get the catch home on a calm day, and sailing safely when the wind came fair.

Photo by Peter Simpson

Photo by Peter SimpsonBuilder Peter Simpson worked directly from Gardner’s Wooden Boats to Build and Use to set up the boat’s molds—though he did find an error in the table of offsets.

Knowing the fine reputation of Rockport Marine, Hayden contacted the yard about the possibility of having the boat built there for him. It’s far outside of the yard’s usual repertoire of premium yacht work, which involves both new construction and restoration. Maybe in a couple of years they could fit it in, Hayden learned. But the yard’s purchasing agent, Priscilla Simpson, told him that her husband, Peter Simpson, one of the yard’s boatbuilders, might be able to build the boat for him at his own home shop during his spare time. Over the winter of 2005–06, it turned out to be an 800-hour project— and an enjoyable one—for Simpson.

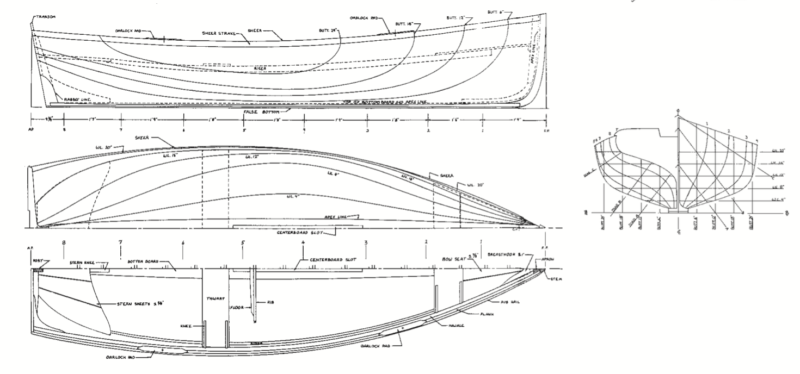

One of the great things about Gardner’s books is that he includes plans and details enough to build the boats straight out of the pages—including the critically important table of offsets, those measurements of every design line in the hull that you must have for lofting, or drawing out the lines full-sized. True, a boatbuilder needs some experience to do this. Simpson, for example, found an error in the table of offsets in the plans developed by Chase, which he said was an obvious mistake and easily fixed during lofting. A novice, however, might have a sleepless night or two and moments of self-doubt over that discrepancy.

Decisions, decisions. The boat could be built in the traditional manner, of course, using the time-tested white cedar planking on white oak steam-bent frames. Simpson, however, used 3⁄8″ okoume plywood planking to meet Hayden’s specification for a glued-lapstrake boat. She’s a rather heavy boat when fully rigged and with all her gear aboard, and yet she’s easy enough to get on a trailer when stripped down to her 200-lb hull weight. And with her plywood planking, she can be led to new waters for different kinds of adventures without requiring time to “take up” and stop the seams from weeping.

Photo by Peter Simpson

Photo by Peter SimpsonThe Moosabec boat is a traditional type, but builder Peter Simpson, working with client Rick Hayden, chose plywood-lapstrake construction for her.

The original boat, which is in the collections at Mystic Seaport, was planked in the carvel manner, meaning it had a smooth hull, with planks meeting edge-to-edge. In lapstrake planking, as the name implies, the strakes, or runs of planking, overlap, and when this is done very competently, the laps visually accentuate the shape of the hull. There isn’t any reason why this boat couldn’t be built in any number of different ways, including traditional carvel or lapstrake planking; glued-lap plywood, as in Hayden’s case; or even cold-molding, that technique of using veneers of thin planking glued up in several layers. The method chosen will reflect the builder’s experience, intended uses, and preferences.

The builder better know something of what he’s about, however. This isn’t the kind of thing a new boatbuilder should undertake, at least not without having done considerable research. It might be a good idea to have at least one glued-lap boat under your belt, completed perhaps with the aid of good instruction books or maybe even full-sized patterns for parts. A hull like this, built upside down over molds, will have to be carefully lined-off to plan where the planks and overlaps will fall. Then, the planks will all have to be “spiled,” or measured one-by-one. These traditional techniques are still necessary for this type of plywood-planked construction.

Photo by Peter Simpson

Photo by Peter SimpsonGlued-lap plywood construction makes a light boat, but many of the elements of building are as they would be with traditional lapstrake construction—including the use of multiple lap clamps.

On the other hand, it seems to me that John Gardner would have been the last person to try to frighten anyone away from taking on a boatbuilding project. Someone with good determination—which is something boatbuilders seem to have in common and in abundance— can gather the necessary skills. Gardner’s books are among the many excellent titles available for any boatbuilder’s library shelf. Better still, go watch someone like Harry Bryan of New Brunswick or Clark Poston of the International Yacht Restoration School of Newport, Rhode Island, or any number of other experienced professionals as they demonstrate boatbuilding skills at The WoodenBoat Show. If you can’t get there, look around: many other boat shows and festivals include skills demonstrations, too. One hour of listening can take all of the mythology and most of the fear out of something like spiling or cutting a stem rabbet. Also, there are lots of schools around these days that offer short courses in specific subjects, and WoodenBoat’s March/April edition always lists about 80 of them (including our own) on several continents. Spending time at boat show skills demonstrations or taking selected classes— or just talking with boatbuilders and asking questions—can save a great deal of time, and maybe even grief, later. The classes Gardner himself taught at Mystic Seaport as far back as the early 1970s were at the root of wooden boat building education, and no doubt he would have delighted in the forest of schools now branching out into specialties and widespread localities.

I had ample opportunities to watch the Moosabec Reach Boat under sail during WoodenBoat’s Small Reach Regatta (see page 20) in August 2007. For all-too-brief a time, I joined Rick Hayden and his friend, Sally Vernon, for a sail in fairly light airs on our final day. This boat is a centerboarder, so she comes about nicely even in a light breeze, but from all reports of her handling she can take quite a blow, as well. Hayden keeps the boat on what’s called a pond in Maine—a lake most other places—and his general feeling is that the boat could be rerigged to increase her sail area. In 15–20 knots of wind on our first day of sailing, Hayden found no reason to shorten sail, and the boat seemed comfortable with herself.

Photo by Peter Simpson

Photo by Peter SimpsonA modest sail plan makes the boat easy to handle, and in this boat any rig other than the original sprit-ketch might seem out of place.

The sprit-ketch rig is handsome and admirable. It simply looks right on this boat. Without the need for standing rigging, the setup and breakdown are easy. Brailing lines on both masts make sail control quick and simple. Coming in to a beach, you can get the centerboard up, brail the mizzen, then brail the main and ghost in on momentum. When the wind abandons you, the sails can be brailed up to clear the rig away and leave plenty of room to row. Hayden and Simpson favor having the forward oarsman face aft, as usual, and the helmsman face forward from the stern sheets and push on the oars. This gives good visibility all around—and it’s a sociable way to row, too. In a very high wind, one mast can be stowed and the other moved to a third maststep located in the forward thwart, aft of the forwardmost mast position, allowing good helm balance with the shortened rig.

The mainsail is loose-footed. The mizzen has a boom set fairly low, which can make moving from one side to the other a tight fit for the helmsman. But Simpson gave the tiller plenty of room to swing up out of the way, which saves the day. In any boat, the choreography involved in tacking or jibing takes only a few rehearsals to master.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzJohn Gardner of Mystic Seaport made a life study of traditional small craft, so when Andy Chase of Castine, Maine, brought him an original Moosabec Reach boat, he documented it knowing that someday later builders would carry on its rich traditions.

I love to row, but I didn’t have a chance to take the oars of the Moosabec Reach Boat during our outing. Everything about her hull form, though, with its transom stern tucking in to leave her waterline a nice, clean exit, points to easy and comfortable work on the oars. Gardner himself referred to the original boat as “surprisingly agile and easy to row,” which has been confirmed in this reconstruction.

I had never seen a Moosabec Reach Boat in the flesh before the Small Reach Regatta. This boat is the first that Hayden and Simpson had seen, too, and their sail number, MRB1, implies that there are no others, save the original. Is this possible? Can such a pretty hull and a practical boat have been overlooked for all these years despite Gardner’s high praise? If so, then the Hayden-Simpson collaboration has done John Gardner proud. May dozens more follow in her wake.

On a work-study project, Andy Chase documented his Moosabec Reach Boat for the Mystic Seaport Museum. The original boat may date to the 19th century.

Plans for the Moosabec Reach Boat are available in John Gardner’s Wooden Boats to Build and Use (Mystic Seaport, Connecticut, 1996).

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Thanks, Tom, for the clear, succinct explanations of planking alternatives. You’ve (again) made accessible the inner world of boat building and handling. How fortuitous that the ’07 Small Reach Regatta brought the Moosabec Reach to your attention. I’ll miss Small Reach but be ever grateful to the Down East Chapter for the years of hosting such grand gatherings (including, I hope, a 2021 finale).