This fine gunning skiff from the bays and coastal lagoons of southern New Jersey might have evolved from the lapstrake beach skiffs that worked the exposed Atlantic beaches of the Garden State. Similarities of line and construction between the beach skiffs and the melonseeds seem too powerful to ignore.

The melonseed’s dates are not certain, and some debate swirls around their history (WoodenBoat No. 180, page 50). Howard Chapelle (American Small Sailing Craft, W.W. Norton, 1951) mentions 1882 as the earliest written reference to the boats. They certainly coexisted for a time with the more famous Barnegat Bay sneakbox, a much easier boat to build. Most observers seem to agree that the melonseed came about in a search for a gunning skiff that could work in more open waters.

The sneakbox, which curiously does resemble a seed that we might find in a melon, works well in marshes and protected waters. In rough water, the sneakbox behaves as we might expect a seed from a melon to behave: it stuffs its low teaspoon-shaped snout into the first appropriately steep wave and submerges. If we clamp an outboard motor to a board bolted through a sneakbox’s transom, the little sliver of a boat will point its bow to the sky and pound our kidneys into submission.

The melonseed, with its sharp-yet-buoyant bow, knows enough to slice right through tiny waves and to climb over the big ones. Firm ’midship sections grant it stability and the ability to carry sail. A shapely, and relatively broad, raked transom eases our concern about waves that might come down on us from astern.

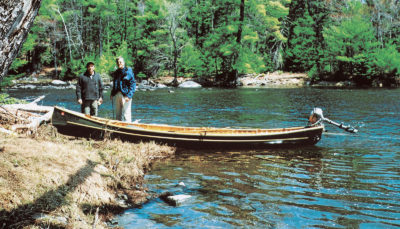

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzAlthough evolved from a Barnegat Bay duck-hunting boat, the melonseed skiff is well suited to recreation. There are several plans available for the type; the one shown here was recorded by Howard Chapelle.

By the time I arrived at the Jersey shore in the 1940s the type almost had disappeared. I never saw an original working melonseed, but the old gunning skiff left a legacy of daysailing catboats along the shores of Barnegat Bay and other shallow estuaries. These often were longer than their forebears (they ranged from about 17′ to 21′ ), and they almost always carried the fashionable gaff-headed sail in place of the gunning skiff’s spritsail. Hunters, then and now, would view the gaff rig as too heavy, too complicated, and too expensive for their purposes.

Most of the melonseed’s descendants carry pivoting centerboards in place of the original’s daggerboard. We’ll find the pivoting board far more convenient to use when sailing across the endless flats of the Jersey bays. So why did the old fellows employ daggerboards? Because day-sailing wasn’t their occupation. They were in the business of shooting ducks—lots of ducks. The longer trunks necessary to house the pivoting centerboards would have been much in the way, and they tended to leak in those pre–plywood-and-epoxy days. They were (and are) slightly more expensive and time consuming to build than the shorter, boltless daggerboard trunks.

As a further convenience, the first builders of melonseeds located the daggerboard trunk far forward below the deck, which cleared the cockpit for the job at hand. A scimitar-shaped daggerboard moved the center of lateral resistance back to where it needed to be. And it allowed the gunner to insert, raise, and lower the board without standing up. The board could be inserted almost horizontally into the trunk.

Many of the original melonseeds appear to have gone together lapstrake fashion, as did nearly all beach skiffs that worked in the surf on the Atlantic side of Jersey’s barrier islands. Other ’seeds were planked smooth— perhaps to account for some hunters’ prejudice against lapstrake hulls, which they considered “too noisy.”

Today, the nature of a melonseed’s construction might be determined by its intended use and by the extent of its builder’s experience. Smooth, plank-on-frame hulls tend not to survive life on a trailer so well as strip-built or lapstrake hulls. Given epoxy, high-quality plywood, and detailed plans, glued-lapstrake construction can be reasonably beginner-friendly. No matter how we decide to plank our ’seed, its backbone will be a sprung plank keel that we’ll bend over molds set up on a building jig. Let’s steam-bend the frames…quicker, cleaner, less expensive, and more fun than laminating them.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzWhen the wind fades, the melonseed’s simple sail can be brailed up, freeing space in the cockpit for rowing, poling, or paddling. The forward sections are fine, but still sufficiently buoyant and stable to float the crew.

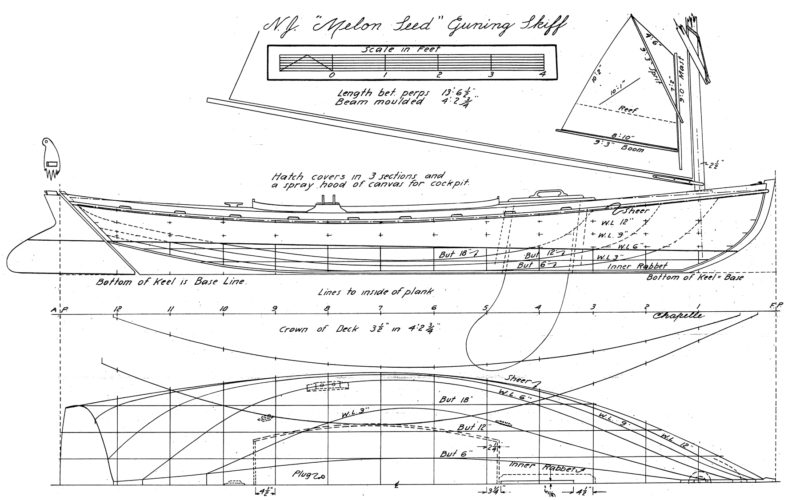

As for construction plans, experienced builders might consider Howard Chapelle’s well-drawn “melonseed of 1888.” He traced the lines shown here from unpublished plans that had been found in the files of Forest & Stream magazine. Large-scale reproductions of these drawings are available from the Smithsonian Institution, Ships Plans, P.O. Box 37012, NMAH–5004/MRC628, Washington, DC 20013; order plan ASSC–78. The drawings describe a particularly handsome boat, and they often were employed by builders of melonseeds during the type’s revival in the latter half of the 20th century.

Along time ago, I had several occasions to sail a melonseed built directly to the Chapelle drawings. The good little boat belonged to Dennis Caprio, former editor of Small Boat Journal. We sailed along the shores of western Long Island Sound. I recall one early autumn morning when (typical of that area) the breeze came on just a notch above slick calm. The melonseed ghosted well. As our weight heeled the tiny skiff, gravity seemed to fill the 51-sq-ft spritsail more easily than it would a modern jibheaded sail (particularly when the sprit rested to the weather side of the canvas).

As we tacked out from the gentrified Westport waterfront in search of a real breeze, a powerboat’s wake caught us broadside. The resulting violent rolling caused the rudder’s pintles to lift from the transom’s gudgeons. The shallow rudder now trailed uselessly astern, towed by the tiller. On its own, the melonseed immediately rounded up into the faint breeze…directly into the path of a huge express cruiser (well, it likely measured about 26′ on deck—big enough). I grabbed the free-swinging rudder blade and sculled the skiff out of harm’s way. Sometimes there’s much to be said for small, maneuverable, easily manhandled boats.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Photo by Benjamin MendlowitzWhen the wind fades, the melonseed’s simple sail can be brailed up, freeing space in the cockpit for rowing, poling, or paddling. The forward sections are fine, but still sufficiently buoyant and stable to float the crew.

In fact, the little melonseed always seemed to do everything better than the design numbers might have predicted. Given any breeze at all, it sailed faster than the diminutive rig would have suggested. It sailed drier than a boat of such slight freeboard had any right. It sailed with an easy motion, and the small cockpit and flat deck seemed acceptably comfortable…at least for a not-yet-old crew.

Sprit rigs, when properly set up, deliver about as much drive-per-dollar as any arrangement. We’ll need to keep adequate tension in the snotter (the line that secures the heel of the sprit to the mast). In strong breezes we’ll snug up the snotter. As the wind dies, we’ll ease the snotter just slightly. If we should ever have to make a sprit for one of these boats, I’ll suggest cutting the stick slightly longer than seems necessary. A little extra length will be, at worst, an easily correctable nuisance. A too-short sprit can ruin the sail’s set and the boat’s performance.

When the time comes to purchase a new sail, let’s visit a maker who boasts more than a little experience with four-edged sails. Folks who cater solely to the racing fleets might want to cut the sail too flat. The spritsail should have considerable draft (fullness) by modern standards, and the point of maximum draft should be farther forward than in a highly strung sloop’s mainsail. Thanks to the current revival of traditional arts and design, we’ll find competent makers of four-edged sails along many waterfronts.

Yes, the melonseed’s shoal draft, likable sailing characteristics, and casual trailerability all contribute to the continued popularity of this 19th-century design. But some of us are convinced that it survives primarily because it is a beautiful boat…well worth building, even if we’re not inclined to blast unfortunate ducks out of the sky.

The Melonseed lines shown here were recorded by Howard Chapelle and published in his American Small Sailing Craft. They can be purchased from the Smithsonian by writing to: Smithsonian Institution, Ships Plans, P.O. Box 37012, NMAH–5004/MRC628, Washington, DC 20013

For a comprehensive list of available melonseed plans, see “A ’Seed Catalog,” WoodenBoat No. 180 , Page 54.

Marc Barto’s plans for 13′ 4″ and 16′ melonseeds are available from The WoodenBoat Store.

You can build your own melonseed or commission custom construction at one of the fine small shops that prosper, to varying degrees, along our coasts. If you prefer fiberglass, Roger Crawford makes ’seeds in that material to the Chapelle lines. He does business as Crawford Boatbuilding. His boats include considerable wooden trim. A good friend of ours refers to them as “fiberglass-hulled wooden boats.”

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Today’s Small Boats Mag email got me reminiscing about my melonseed. PATIENCE was built by Alex Hadden from Chapelle’s plans which he obtained from the Smithsonian. I kept track of her progress on this webpage which shows her construction. What a great boat. She is the epitome of what Small Boats Mag is all about.

Walt Allan

P.S. I sold her this past summer as jumping about in her got hard for my 77 year-old body.

Great boats! It will 7 years now sailing my Barto 16, RIVUS. It’s a joy to sail, fast. stable and not bad to look at. There are a few dozen more ‘seeds of various designs listed here.

Same reason I sold my Mark Barto Melonseed, built by Howard Katz of Arlington, Virginia, in my early 80s. Beautiful boat. Sold to a gentleman on Cape Cod some years ago.

First one I saw was one built by Joe Liener in the late 1940s to the Chapelle lines. I know of only two other sets taken off old boats. Joe planked his in aircraft plywood as he had ready access to it, working in the small boat shop of the Philadelphia Naval Yard, a shop he would eventually run. The detailing on his ‘seed is worth a study, things like a way of handling the transom as it extends above the aft deck that allowed a small outboard to be used. Joe used his boat in the South Jersey marshes, carrying it in the back of one of the classic big American station wagons.

His boat, I think, is directly responsible for the revival of interest, as several apprentices saw and sailed it in 1976, then went on to build them, which, in turn, let others see them.

As far as I know, only three sets of plans survived from the working days: Chapelle’s, one drawn by Wayne Yarnell from a 16 footer, and one measured by Barry Thomas at Mystic. I don’t know of any historic ones in museum collections. I believe that Joe’s is in the Independence Seaport Museum collection.

A slightly different 12′ melon seed, was documented by Geoff Scofield and Mike Alford at the North Carolina Maritime Museum. They built a replica of the boat which was still sailing on one of the lakes in North Carolina in the ’90s. I believe the original boat still exists and may be on exhibit at the Delaware Bay Estuary Center, in Bivalve, New Jersey, or at a recently organized Life Saving Museum near Cape May Courthouse, NJ, where the boat was owned.

Who is Wayne Yarnell and where can the plans for his 16 footer be found? Any other info on it?

In the November 2016 issue the “Seaford Skiff” of Long Island’s Great South Bay was written up. “Skiff” and melonseeds are like sister and brother. Mystic Seaport has a few “skiffs” including my sister’s, named RoRo. The museum also has plans. These are delicious little boats. And they are wonderful training boats for kids (like me, some 60 odd years ago). Mystic also has a replica they built a few years ago in their boat livery. A great way to find out how wonderful both types of boats are. But a wee comment—if you look at the foto with the man on the foredeck next to the mast, imagine that you have tied up to a dock with only room for the bowline. Imagine swinging around the mast to then step on the dock. Imagine doing that after frostbite racing. I do not have to imagine how cold the water is if you don’t make it around.

Enjoy and Merry Christmas to all

The man in the images was me 30 some years ago and I wouldn’t try that trick now at 70 regardless of the melon seed’s stability. Of course the boat is floating next to the shore in 2′ water in a sandy-bottomed lake in New Jersey.

So Roger, you no longer can do the Laser/Finn trick: Lean the boat way over one side then run around the mast on the other?

I’m glad Small Boats has reprinted this article. 1st, in response to Ben picking on Roger for no longer doing the “Laser/Finn trick.. Long before Lasers were ever seen on the Great South Bay a few of the kids graduated to the Finn class and brought the lean the boat trick to the Finns… The aura of Paul Elstrum as the animal sailer attacking the wind and waves around a racecourse was compelling….

2nd.. Mystic Seaport had a special display of some of the boats which were stored away from view and called it-“-If they could talk”–one was supposed to be my sister’s Seaford Skiff.. I drove all the way from the Outer Banks of NC to see it.. My sailing buddy of my youth, Brian Donohue, is a volunteer at Mystic. He told them a person who had actually sailed her would be coming… Imagine our dismay when we found out that they had decided NOT to display the RoRo.. After that disappointment we lifted each others spririts by walking among the boats on display.. We knew the backgrounds behind most of the boats. As we walked and talked we found people starting to follow us as if we were tour guides… .. Hmm?…. I wonder if anyone can match my claim to fame… I was the last to sail a boat donated to Mystic (the RoRo) and also the last to sail another boat donated to another museum….. My uncle donated his W-Cat built by Wilbur Ketchum to the Long Island Maritime Museum. I was the last to sail the Yes Pop….

Marc Bartow built a few and we usually see one at the Chesapeake Bay Small Boat Festival in October (but not this year) When I met him a few years ago, he was living on old Dickerson mid-cockpit that belonged to a Mr. Roberts, who owned the Worton Creek Marina in Chestertown, Maryland.

The boat in the images was begun by Valerie Danforth to the Chapelle lines. Valerie was one of John Gardner’s apprentices at Mystic Seaport and brought the backbone and mold to Philadelphia Maritime Museum (PMM) when she came there to work with me as a boatbuilder at the Museum’s Workshop on the Water. The boat was later finished by Peter Lauser of New Britain, Pennsylvania. The sprit rig was hastily cobbled together using bits and pieces from two 12′ duckboat class sneakboxes. The images were taken by Ben Mendelowitz at the Tuckerton Decoy Festival in about 1982 as part of a portfolio of Delaware Valley/Jersey Shore boats he was putting together for his first Museum exhibition.

I was one of Joe Liener’s “students”, referenced by Ben Fuller, while I worked to build and organize PMM’s Workshop on the Water, beginning in 1978. Sailing the “Seed” was icing on the cake during my many visits to Joe’s home to learn boatbuilding and vernacular New Jersey/ Delaware estuary small boat lore, of which Joe was a Master. The lines of his boat were provided by W.P. Stephens who took them from a half model. According to Joe, Stephens felt that the melon seed was the best boat of its size. While I’ve never made the comparison between the two, Joe believed that the boat he built had less hollow in the fore sections than the Chapelle version, giving it more buoyancy to carry the weight of the rig, and sweeter buttocks for her entry.

The lines of Joe’s boat were taken by Jon Etheredge while he worked with me as Master Boatbuilder at the Workshop on the Water in the 80s. I took those lines, for a 13.6″ boat, with me to North Carolina where I expanded them to make a 15′ version. Joe and I had often looked at the Yarnell 15′ melon seed lines and agreed that she was more catboat and less melon seed because of her fuller lines. I wanted to build a 15′ melon-seed that had the elegant sailing qualities of Joe’s boat. Dave Lucas, boatbuilder of Bradenton, Florida, and I have seen over 22 built to the new lines and I think it has worked.

Roger, did you or John record the little detail on the transom that allowed a small outboard to be fixed to the ‘seed. As I recall, the transom extends above the afterdeck on these in a graceful arc. Joe cut away the forward corner of the transom extension so the top harmonizes with the sheer, but left it proud for a few inches in the center so you had enough meat for the motor, and made the arc of the transom high enough for space to seat the outboard.

I’ll have to look! It’s been so long since I looked at our plans that I can’t remember.