Hird Island is surrounded mostly by marsh grass, but along its easterly face a meandering deep-water creek sidles close to shore where a few dwellings and docks have sprung up. Here it’s quiet except for an occasional outboard motor. Ashore, you travel in electric golf carts instead of autos. You’re in the heart of Georgia marshland—tidal, sheltered, and, most of all, silent where the call of birds is apt to be the loudest sound you’ll hear.

Because of the island’s proximity to the Atlantic, there’s a surprising current from the incoming and outgoing tide, so rowing isn’t always the best way of exploring, and the winding nature of the meandering creeks (there are miles and miles of them) oftentimes makes sailing a challenge. To fit in appropriately, Doug Hylan (who has a cottage on Hird Island) selected electric power and a simple skiff of plywood with a centerboard and small sail to be used when the wind suited. He keeps her in a shed when he’s away, which is most of the year, but in only a few minutes after arriving he is able to launch and set her up for use.

Photo by Anne Bray

Photo by Anne BrayThe reedy shallows of Georgia call for a shoal-draft boat that can easily navigate the channels—and with its electric motor, this skiff can do so without disturbing the peace and quiet.

Energy, of course, comes from batteries, a pair of 12- volt, deep-cycle ones housed under the forward seat in dedicated compartments each side of the centerboard trunk. They connect to a Minn Kota Endura 30 trolling motor that’s been cut down to fit within a capped well, completely hidden from view. The motor can be hoisted clear of the water and a plug inserted in the opening, which reduces drag when sailing or rowing. So rigged, the motor still lives inside the well. A transom-mounted rudder steers the boat; the motor is fixed in the straight-ahead direction. The rudder operates by means of a continuous steering line easily reached from anywhere in the boat. You just grab the line (it runs through a series of eyes mounted on the inwale) and pull or push on it to move the rudder and steer the boat—and it works under sail and oars as well as under power. Initially, it’s not as intuitive as a wheel or tiller, but you soon get used to it, and steering this way becomes as natural as any other method. One of its advantages is that there’s enough friction in the system so the rudder stays where you put it and the boat holds its heading without your having to tend continuously to steering.

Motor speed and direction (i.e. forward and reverse), while normally controlled by twisting a stock trolling motor’s steering handle, here are operated by rotating a knob mounted on the side of the boat within easy reach of where you sit. A setup like this requires some rewiring and extra carpentry, but is well worth it in terms of convenience.

Watertight compartments in the bow and stern keep the heavy batteries from sinking the boat if for any reason she should accidentally fill with water. The motorwell is a box within the aft compartment accessed by a deck hatch. (You can access the compartment itself through a door in the bulkhead.) Between the permanent forward and aft seats, there’s a removable thwart for rowing. Being flat-bottomed, this is an easy boat to walk around in, although you’ll find yourself sitting side-by-side with your companion most of the time, leaning comfortably against the backrest and enjoying the view—and the silence of electric power.

Photo by Anne Bray

Photo by Anne BrayWhen there’s room to tack and depth to lower the centerboard, the skiff’s dead-simple but very effective lugsail lets the breeze do the work.

In using the boat, Doug usually goes electric: “While I first envisioned this skiff as doing a fair amount of sailing, in fact our usage has evolved in two other directions, both based on electric power. The first is wine-and-cheese sunset cruises with my wife, Jean. Here the quietness of the motor and the private proximity of the passenger pro- mote lovely conversations (perhaps helped along by the wine). Our second favorite use of this boat has been for wonderful moonlight cruises. Sailing has receded partly from my own laziness, but also because the range under batteries has turned out to be far more than I expected.” The range has been more than four hours at maximum speed.

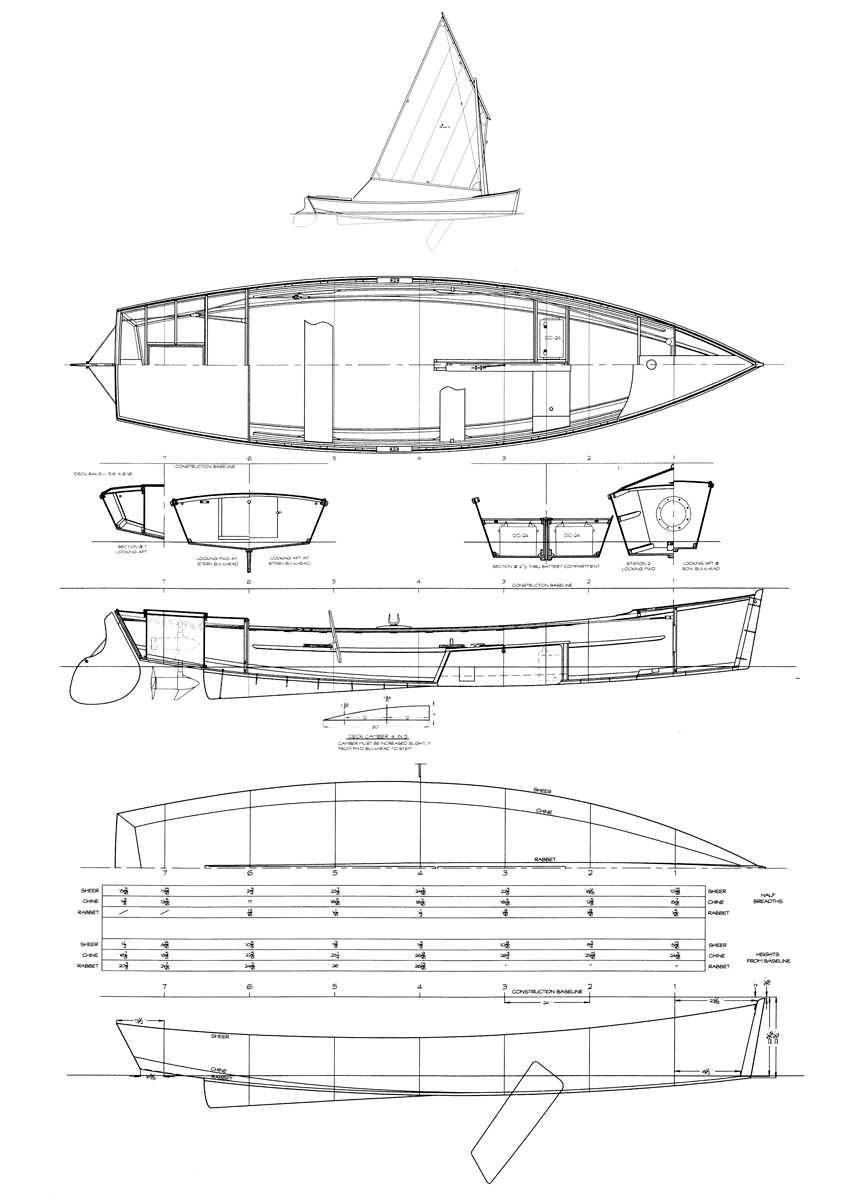

Although Doug used stitch-and-glue construction for the boat he built for himself, he decided that conventional chines would be easier, so he has drawn the plans that way, with station molds 2′ apart erected on a ladder-type frame to define the hull shape. The forward half of the hull is absolutely flat on the bottom, but as it approaches the stern, the bottom takes on a shallow V-shape to reduce its drag, especially while heeled under sail.

Photos by Maynard Bray

Photos by Maynard BrayTop—The skiff’s electric motor, which is nicely hidden away in an aft compartment, and can be hoisted out and replaced by a fitted cap to reduce drag when rowing or sailing. Above left—Batteries reside underneath the rowing thwart. Above right—The rudder line runs in a continuous loop just below the gunwale, always in easy reach.

Doug Hylan’s drawings consist of six sheets: a sail and spar plan; lines and offsets; construction; building jig and stem patterns; plywood panel layouts; and molds, transom, and rudder patterns. The set includes basic instructions and a CD of photographs. The skiff’s sides are of 1⁄4″ plywood, and the bottom is of 3⁄8″. In building, you begin by gluing two sheets of each thickness together for length, then marking and cutting out the pieces. Seven molds are needed, and their shapes come from full-sized patterns. They’re set up on the ladder frame as depicted and described in the notes, along with the inner stem and transom. Sides are bent around, the chines are added, then the bottom—and, before you know it, you have a hull. From there, with the boat turned right-side-up, it’s a matter of adding the remaining items like centerboard trunk, bulkheads, decks, etc. In all, it’s a pretty straightforward building job suitable for first-timers.

After watching Doug build the first of this design and admiring its characteristics (and how quickly it went together), I was eager to try it out. This happened at Doug’s place in Georgia. We sailed her and ran her under power along those narrow, marsh-grass-bordered creeks and found her perfectly suited to calm water and moderate winds. Speed is fine propelled either way, the sail being large enough to make her move well and respond, and there being enough thrust (30 lbs at full throttle) to be more than sufficient to move along at a good clip even against an adverse current.

But, best of all, was the silence!![]()

Doug Hylan’s plans for the Hird Island skiff are characteristically easy to follow and complete. The hull is marked by its simple construction and good looks.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2009 — for more information, visit Hylan & Brown Boatbuilders.

Love the design. Love the low profile.

This boat was one of the inspirations for going electric with my own boat, John Welsford’s Walkabout design. It’s another slippery hull that goes fast under oars, so electric seemed likely to work. The motor is an EP Carry outboard, modified to replace the tiller with rope steering via a forward mounted wheel, move the motor control into the cockpit, and control the tilt from in the cockpit with a telescoping pole. First try was with an e-bike battery, which briefly worked but exceeded the motor voltage limit. Now with a 26 V LiPO battery and a fold-down 180 W solar panel range at 4 knots is unlimited during summer daylight and 4 hours on battery after dark. My cruising grounds are the Sacramento Delta, an area of winding sloughs that sounds a lot like the Georgia marshland that Mr. Hylan designed his boat for.

There’s a photo of my boat here.

We lived on those Georgia marshes for twenty years and meandering along the creeks in small boats was a year-round delight… until jetskeets arrived on the scene and began tearing around the winding waters. It became a safety issue so we mounted tall bicycle-flag whips on the boats and kayaks so jetskeets would see we were around the corners and might avoid running us down. There were some VERY close calls. The local dolphins didn’t care for the jetskeets at all either.

Love this. Wondering what kind of electric motor and battery set up is being used? Could see using this tooling around South Sound.