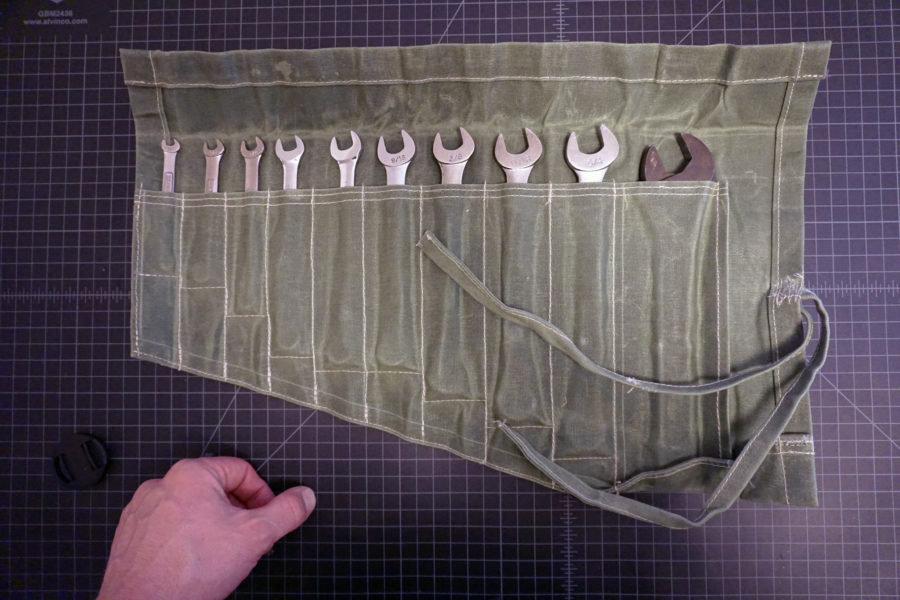

Two pieces of 9mm plywood glued together create a side fence for a jack plane. For larger planes balance on the work can be an issue. The small section of this fence could be made thicker to better balance the jointer plane over the work. photographs by the author

photographs by the author

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.

One thought on “Planing Edges Square”

Comments are closed.

Stay On Course

Clever, simple, economical and effective! Now why didn’t I think of that myself?!