Kathy Mansfield

Kathy MansfieldFrançois Vivier designed the handsome pocket cruiser Pen-Hir for his own use. He cruises the boat for up to two weeks at a time, often singlehanded, along the Brittany coast.

Pen-Hir is a very pretty little 24′ 7″ pocket cruiser designed by naval architect Vivier Vivier. Some of my favorite moments at the big French traditional boat festivals have been watching her sail purposefully through strong tides and sometimes strong winds in the company of schooners, pilot cutters, and fishing boats. There’s always a large sail-and-oar contingent too, numbered in the hundreds, and there we are among friends, because Vivier has designed a large proportion of them, as well as quite a few of the larger boats. There are sleek double-enders, plumb bows and transoms, raid boats like his sprightly Stir Ven design, and a proliferation of rigs from gaff and lug to gunter and marconi.

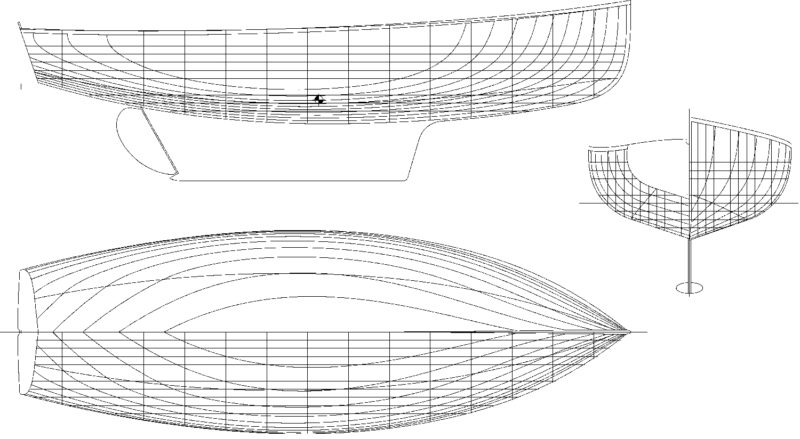

Vivier spent four years considering the design for a small, fast, good-looking cabin sailboat for himself that he could cruise for two weeks in the summer along the coast of Brittany, often singlehanded or in shallow waters. He wanted to keep it simple, without the need or expense of winches and windlasses, little to go wrong. His inspirations were the small boats of Alden and Crowninshield, the purity of Herreshoff, but updated for modern use with more beam and a larger cabin. He also added to the mix the traditional look of workboats from western Brittany that were sailing at the same time in the early 20th century, with a plumb stem and short counter, but adding the lower freeboard and elegant sheer of classic yachts.

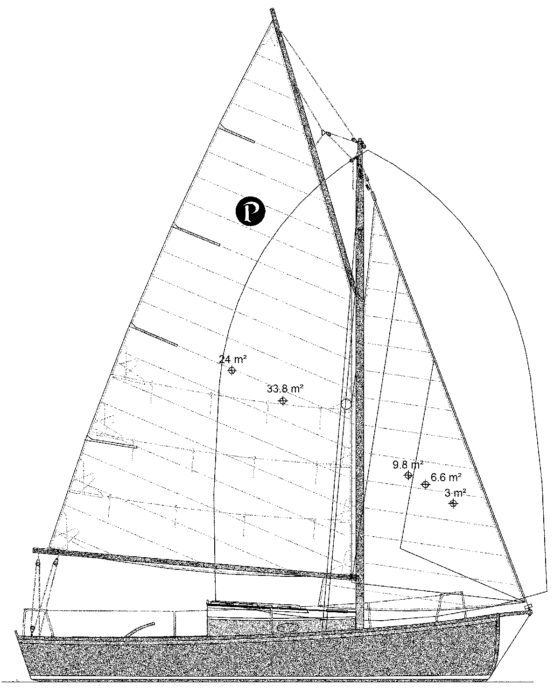

If the boat was to be trailered to different cruising areas as well as sailed locally, Vivier wanted to keep that process simple as well. A gaff rig, when peaked high enough, can point to windward like a marconi sail, but has the added advantage that the mast is in two parts so the spars can be designed the right length to fit inside the boat for trailing. The mast can also can be raised without assistance with a counterweight and tabernacle, with dedicated pole and purchase. This was his rig of choice, though he has designed a marconi option as well.

Vivier came to the project with an enormous amount of experience and a wish to try out new ideas with his own boat. A naval architect for many years designing large ships, later working as director of the French Shipbuilding Research Institute and co-founder of the French traditional boat magazine Le Chasse Marée, he has designed an impressive range of boats. He’d already designed a 27′ 10″ (8.5m) cruising boat, the Toulinguet, and a smaller weekend centerboard cruiser, the Méaban. But with the aim of simplicity, he considered a shallow, long keel and rudder, instead of a steel centerboard and hydraulic lifting gear. Weight could then be better distributed, but would the extra wetted surface slow down the boat? Here Vivier comes into his own, for careful research and analysis that might be shared with the boatbuilding community is something that comes naturally to him. Drag calculations showed that it is the number of appendages that is the critical factor rather than the wetted surface area. A shortish classic keel and integral rudder with sufficient sail area can give better lateral resistance at slow speeds than a centerboard or fin keel plus one or two rudders.

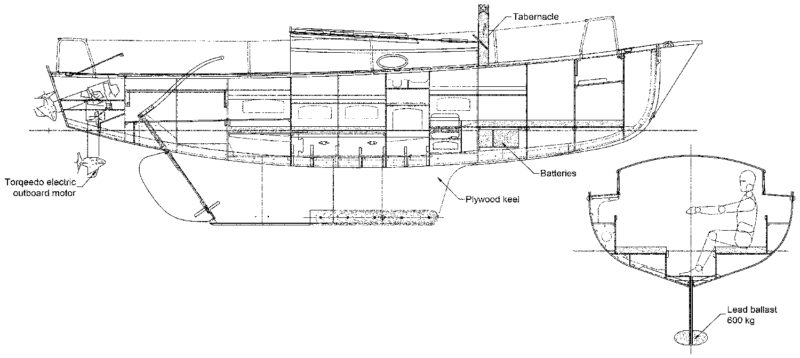

For anchoring in shallow or drying areas, Vivier then added detachable legs that would store under the cockpit side decking, to be mounted on the hull sides to keep the boat balanced on the ground. “For my father, the length of the cockpit is now determined by the boat’s draft so the legs will fit,” his son, Nicholas, said. A 13″ sculling oar also fits neatly, partly under the cockpit. It must be one of the pleasures of designing a boat.

Kathy Mansfield

Kathy MansfieldIn the interest of conservation, Vivier used birch plywood from Finland for the prototype Pen-Hir’s hull. He also conducted a longevity study on this wood and his method of using it, with promising results.

For his own boat, but not necessarily in future builds, Vivier looked at environmental considerations. Instead of using marine plywood manufactured from tropical hardwoods, he found a sustainable birch plywood made in Finland, and as a side project managed to get funding to study the durability of different types of marine plywood. Plywood samples without any protective coatings were half plunged into seawater for two years. All were damaged by the end of that time, showing that protection is essential, though mahogany survived best. The tests show too that current durability classes are not relevant to boatbuilding. Mechanical tests including density pointed to birch ply as being preferable. Despite a high density, birch was used in early airplanes. There has been no problem in the five years since the boat was built, and two others using birch plywood have been built since. Okoume plywood would need an increase in thickness, particularly in the keel area.

Pen-Hir, named after an attractive peninsula near Camaret in Brittany, was built by Nicolas at Icarai Boats near Cherbourg. Once the plywood pieces are computer-cut to shape, the boat can be ready for planking and much of the accommodation built within two weeks at the yard with two or three people working. The bottom planking is a single sheet of plywood and the sides are planked vertically, a method that Vivier has used extensively and thinks can be more accurate than using long horizontal planks. It also makes a strong, nicely rounded hull, avoiding the hard chines that often identify a plywood boat. The bulkheads and keel are made of strong, criss-crossed layers of birch plywood, the latter with 1,323 lbs (600 kg) of lead at the bottom. The bilge area and side planking are composed of two layers of 6mm ply, and the single bottom section is 12mm. The entire hull is epoxy-sheathed, and any exposed plywood edges are protected by a hardwood batten, epoxy glued and nailed in position. The curved coach roof top is laminated over a mold and glued to the oak sides. Sustainable woods are used throughout the boat: oak for floor timbers and coach roof coamings, northern pine for accommodation below, Douglas-fir for beam clamps and spars. The mast is hollow and mounted on deck, saving room down below. The bottom is coated with a long-term antifouling mix of copper and epoxy.

Kathy Mansfield

Kathy MansfieldPen-Hir sleeps two in a forepeak double. A curtain separates the sleeping space from the saloon and galley, which are airy and welllighted.

My first view of Pen-Hir on the water was of a classically low, light aqua hull and nicely proportioned oak–sided coach roof with white-painted decks, her sheer echoed in a solid oak rubrail. Her plumb bow under a short bowsprit is curved at the forefoot; she has a very ample cockpit with a short transom.

The boat coasted along in very little wind, her high-peaked gaff rig, almost gunter, set off by classic stitched sails and Douglas-fir spars. A short transom holds a mainsheet horse, keeping the cockpit free, and a well holds a Torqeedo electric engine, equivalent to about 6 hp, which can be tilted out of the water, giving a range of about 20 miles at 4 knots on a quiet sea. Oars plus a sculling notch at the stern gave extra options for harbor work. The tiller is convenient for the helmsman in any position and easily lifted out of the way. The side decks were clear, not a winch to be seen, with the mainsheet on a block and tackle and secured with a cam cleat. The jib, about 108 sq ft, is small enough to sheet in to cam cleats as well, as are the halyards. I liked the small anchor well and cover, everything neatly to hand, and the stainless-steel pulpit and guardrails were unobtrusive. The oak grabrails on the coach roof and the bronze cleats give a traditional touch.

The saloon feels spacious and bright with no centerboard trunk or mast to get in the way, with white bulkheads, oval portholes, and shelves above the two full-length berths, plus easily accessible and ample stowage and plenty of wood trim. There is a 60-liter water tank under the starboard berth, a small sink and galley stowage at the forward end, and a sliding chart table at the aft end near the cockpit hatch. At the forward end of the port berth there is a combined stove and heater. A table slides out from under the cockpit, and it can be positioned below or in the cockpit. A curved opening to the forepeak with a full double bed and more stowage plus batteries underneath is lightened by a hatch above. A curtain separates this area from the saloon, and a chemical toilet means no plumbing or through-hull fittings.

Kathy Mansfield

Kathy MansfieldPen-Hir has proven herself in winds over 22 knots, and she also ghosts well in light air—often passing much larger boats.

I’ve sailed now in a wide range of wind strengths in Pen-Hir, notching up a Force 6 last May in the Gulf of Morbihan when we sailed outside the protective gulf, Vivier sailing singlehanded so I could take photographs of the start of a parade of sail. The commentators later mentioned our presence there—no other light plywood craft under 30′ were to be seen, nor much else besides traditionally built workboats. With a couple of reefs, a sense of adventure, and a fine skipper we were in good control. At the other extreme, in light winds, and in moderate winds as well for that matter, we have slipped past boats much longer than us with great ease, our keel keeping us from slipping sideways as we work upwind. She tacks firmly and easily despite the keel, and does not feel tender. We have not been in waters shallow enough to have the keel impede our progress, with the exception of one lunch spent at a slight angle while the tide came in. The hundreds of festival boats that we have encountered at times make for a short, steep chop that Pen-Hir hardly notices, and the thought of cruising away toward the nearby beaches, the islands farther away, the coastal towns, was a very enticing thought indeed. I can envisage her far from the Brittany shores, exploring Penobscot Bay in Maine, and I think Alden and Crowninshield would have nodded approvingly.![]()

Plans for the Pen-Hir are available from François Vivier, Naval Architect.

Pen-Hir Particulars

LOA 26′ 1″

LWL 23′ 8″

Beam 9′ 2″

Draft 3′ 10″

Sail area 364 sq ft

In Pen-Hir, Vivier was inspired by the good sailing qualities of the knockabout sloops designed by B.B. Crowninshield in the early 20th century, as well as by the pure simplicity of Herreshoff boats. But he also sought a larger cabin and a wider hull than those boats carry. The plumb stem and short counter are typical of Vivier’s home waters.

Any chance someone can share the paint used on the topsides? Including the paint manufacturer, paint name and paint code to assure duplicating that beautiful color? Thank you.