Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamMarsh Duck, designed by Scot Domergue, combines the performance of a sailing canoe with the range of an expedition camp-cruiser.

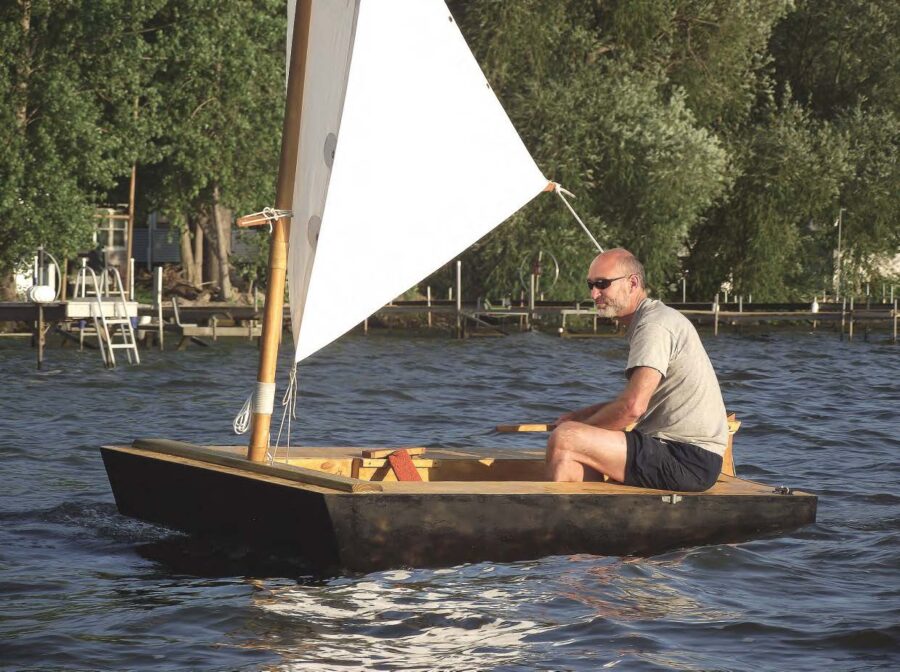

Scot Domergue wanted a boat that didn’t exist. It had to have accommodations for sleeping aboard under a solid roof and the performance of a sailing canoe. It had to be burdensome enough to carry supplies for extended solo cruising yet easily driven with sculls and a sliding seat; tough enough to drag across a rocky beach yet light enough to tow on its traler behind a bicycle. He went to the drawing board and worked up about two dozen designs. The last one, the narrowest he dared draw, became the Marsh Duck.

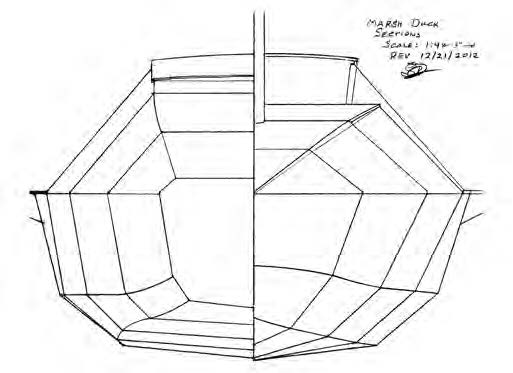

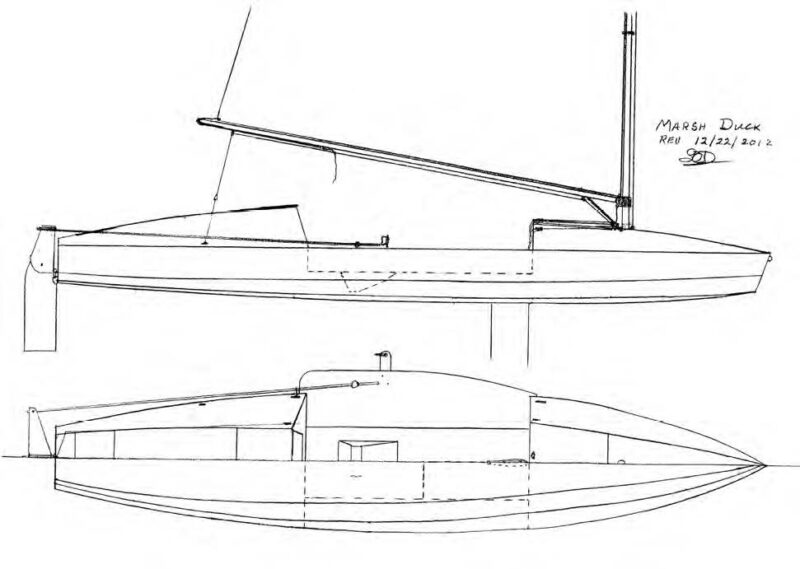

The boat is 18′ long and has a beam of 43″. The integral wings amidships increase the span to 54″. Short, easily removable outriggers add another foot to the beam. Fiberglass and epoxy over stitch-and-glue construction with 1⁄8″ and ¼” plywood brings the boat in, without sailing and rowing gear, at about 130 lbs.

Sailing performance was Scot’s primary focus when he was designing the Marsh Duck. His initial concept was inspired by the YAKABOO, a sailing canoe Frederic Fenger used to cruise the Caribbean in 1911. The Marsh Duck’s hull form was adapted from that of a more modern sailing canoe, the IC–10—an international class of sailing canoe. Scott converted the IC–10’s hull to a double-chined form appropriate for construction in plywood.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamUnder sail, the boat is steered via two push-pull tillers.

Under sail, the Marsh Duck’s canoe ancestry is evident. Sailing requires you, the live ballast, to look lively. The side decks provided me a good windward perch when the sail powered up and the Marsh Duck took off. Under the 107-sq-ft mainsail, the Marsh Duck was quite sensitive to the rather fluky offshore breeze, so I shifted my weight often and kept the sheet out of the jaws of its fairlead/jam cleat. The rudder, fully deployed for sailing, provided instant and dramatic response to my touch on the twin push-pull tillers. One of my own boats is equipped with a single push-pull tiller, so I thought I’d adapt instantly to the Marsh Duck’s system. I did, but only on the starboard tiller. On the port side I steered with starboard side reflexes, and the Marsh Duck responded by darting about like a housefly. More time at the helm would solve that problem. When I had steady wind and steered a smooth course, the Marsh Duck flew along and provided an exhilarating ride.

I had no trouble keeping the boat upright during my sailing trials, but I did a capsize drill to see how easily I could recover from a dunking. The mast and sail kept the Marsh Duck from completely turning turtle, and she floated high on her side. After making sure that the main sheet was free, I swam around the stern and grabbed the daggerboard. It didn’t take much of a pull to get the boat upright. Getting back aboard was very much like reboarding a kayak after a capsize and wet exit. To keep from pulling the Marsh Duck over on me, I had to kick and lunge to get my weight quickly amidships. A bit of tidying up in the cockpit, and I was ready to get underway again.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamFor rowing, the boom is lifted clear of the oarsman. Foot straps are unnecessary, as the seat is inclined aft to ease recovery.

Scot keeps the carbon-fiber mast up and the sail furled on the boom while rowing, which he normally does in calm conditions, preferring to sail whenever there’s a useful breeze. I had plenty of clearance under the boom for rowing. A recess in the cockpit floor serves as a foot brace. It’s fitted with a mating plug to provide a flat floor while sailing. The recess is simple, effective, and comfortably angled. There was no need to have my feet strapped in, as in a racing shell, because the tracks for the sliding seat are set on long wedges that had enough downward slope to bring me aft through the recovery of my stroke.

The rowlocks are standard for racing shells. The gates that close over the looms keep the oars from popping out of the locks, but if the boat rolls excessively they’ll push the oar handles into your thighs. Scot’s not as big as I am, so the locks weren’t set at a height that fit me well. While I had no trouble rowing at right angles to waves, I did get hung up when the waves were at an angle and induced some roll. A simple fix would be to mount the outriggers above the wings instead of below them. Builders should check the rowlock height and adjust as necessary—it’s essential for open-water rowing. I should mention that I’ve never been a fan of using a sliding seat and outriggers on open-water rowing boats. They were designed for fast, light boats racing on flat water. On rough water the overlapping handles of long sculls aren’t well suited for a rolling boat. Rowing a heavy and relatively slow boat with a sliding seat is hard on the knees. A fixed thwart and a shorter stroke, in my experience, are a better match for waves.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamDesigner-builder Domergue transports Marsh Duck on a bicycle trailer.

When I rowed across the wind the tall, bare mast and the furled sail on the boom caught enough wind to make the boat heel, enough to push the downwind oar handle to my thigh. The sliding seat rig, normally centered on the cockpit floor, can easily be set to the windward side to level the boat. On flat protected water I rowed at a relaxed 4 knots, sustained 5½ knots, and topped out just shy of 6 knots. The light, narrow hull of the Marsh Duck is easily driven, but when there’s enough wind to scuff up the water, it’s time to let the sail take over the work.

The Marsh Duck’s bottom is a wide, well-rockered panel without a skeg, so the boat can spin around without much provocation. It relies on the rudder for tracking. The rudder is rigged with two push-pull tillers, each captured alongside the cabin with a thin, cleated line that offers a little friction so I could set the rudder straight or at angle and the line would lightly hold it. Over a long haul, that works, but in close quarters that require a lot of maneuvering, every adjustment of the rudder is an interruption to rowing. Another lesser issue is that the rudder, while nicely foil-shaped to reduce drag, is extra wetted surface to pull through the water. I’d prefer to have it retracted. With the rudder up I could steer with the oars, but the stern tended to swing wildly as it lifted between strokes because my weight would slide forward at the end of the stroke. When I rowed with the rudder partially retracted, leaving the leading edge angled slightly down and immersed a few inches, it provided tracking while still allowing me to steer with asymmetrical pulls on the oars. While the absence of a fixed skeg offers more nimble steering while under sail, I’d suggest adding one to keep the stern in line while you’re rowing.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamMarsh Duck’s rowlocks are standard racing shell equipment. The shop-made outriggers are mounted on wings built into the hull. The rudder is retractable for rowing, and provides sensitive steering under sail.

The Marsh Duck has two large compartments with watertight hatches. The forward compartment can hold quite a bit of equipment. More gear can be tucked into the space under the cockpit; heavy items such as water, food, and cooking equipment stowed there can provide additional stability and keep the bow light to lift over oncoming seas.

The aft cabin felt quite roomy to me, vastly more spacious than my sneakbox, where there’s scarcely enough vertical clearance for sleeping on my side. The Marsh Duck’s cabin doesn’t have sitting headroom, but I didn’t find it at all claustrophobic. From transom to bulkhead there’s 6′ 4″ of length, plenty of room for me, at 6′, to stretch out in. There was enough width along that length to lie with my knees tucked up. Holes in the bulkhead forward provide access to the storage space under the cockpit so the cabin doesn’t need to get cluttered with gear. The companionway door is plexiglass and lets in plenty of light. The sliding hatch overhead can be moved aft for extra ventilation or stargazing. There’s a solar panel on the cabin roof to charge an electrical system for cabin lighting.

Having comfortable sleeping arrangements aboard the Marsh Duck will save a lot of time you’d otherwise spend setting up camp ashore. You can sleep at anchor or pulled up on the beach and in the morning be ready to get underway in just a few minutes.

The Marsh Duck, one of a new breed of solo cruisers, combines the compartments and the profile of an ocean rowing boat with a fast slender hull. It would be best for someone who’d enjoy, and develop the skills for, high-performance rowing and sailing. In the Marsh Duck you could ably answer the call of lifelong coastal cruiser Audrey Sutherland: “Go simple, go solo, go now.”

Plans are available from Duckworks Boatbuilder’s Supply, www.duckworksbbs.com/plans/domergue/marshduck/index.htm.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamParticulars

LOA 18′

Beam 3′ 6″

Draft 4″ – 8″

Sail area 107 sq ft

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamMarsh Duck combines the best elements of a sailing canoe, an ocean rowing boat, and a racing dinghy. She carries three reefs, and her 107 sq ft of sail may be quickly reduced to 25 sq ft.

Very interesting! Especially the comments from cruising experience…and notes re ‘tuning’ for the individual. I could see using this boat all right but might screw it up with trying to push each compromise too far (my biggest problem, trying to do everything with everything!)

Really cool boat. Are you considering ama’s or is the beam adequate enough that they would not be necessary?