In the spring of 1970, the Marine Historical Society, now the Mystic Seaport Museum, sent out a flyer inviting recreational rowing enthusiasts to a “Small Craft Conference–Rowing Workshop” sponsored by the Small Craft Laboratory, which had been started by then Associate Curator John Gardner. Topics would be pulling boat design, reviving recreational rowing, and comparing participating boats. The flyer also suggested that participants submit a design for the “perfect boat.”

Capt. Pete Culler took an interest in the design challenge. A yacht captain, boatbuilder and designer, he had designed and supervised building the schooner INTEGRITY for his friend and sometimes employer, Waldo Howland, owner of Concordia Company. Pete and Waldo discussed the idea and Pete sketched a simple 13-1/2′ flat-bottomed skiff, similar to a 15-1/2-footer he had built in 1968. Waldo liked the result, and mimeographed a pamphlet about it which was distributed at the workshop. In it he wrote that the new skiff was “a learner’s boat for rowing and sailing, and for fun and satisfaction. Suitable for instruction and general use in summer camps, in youth training programs and at home. Rowing is fun if the boat is the right model. Big enough to be useful, long and fine lined enough to row easily. With sufficient length, she will be stable. There are many uses for a good skiff besides rowing alone. Pulling up on a beach for swimming & picnics. Go fishing or clamming. Carry passengers or cargo. Imagination and a bit of water is all you need.”

Designed to be built by amateurs, the skiff received an enthusiastic reception and, after the workshop, Culler drew up plans for what has become a classic, the Good Little Skiff.

Ben Fuller

Ben FullerThe plans don’t include a footbrace for rowing; a board spanning frames serves as a simple and effective stretcher.

I bought my 13′ Good Little Skiff, SMILE, in 1977 from Fred Kemp when he and I were working at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. I rowed and sailed her on Chesapeake creeks, then took it with me to Mystic Seaport where she was my commuter boat for more than a decade, then to Maine. The bottom is her second, as the galvanized fastenings into the chines used by Fred throughout the boat (except for the copper-riveted planking) had started to weep after 40 years. Lately she’s been in storage, and in honor of the 50th year of the Small Craft Workshop, I recommissioned her.

Traditionally built, the Good Little Skiff is perhaps 50 to 60 lbs heavier than a similar craft built today in plywood. It has more flare than most and a little powderhorn in the sheer, something Pete, unlike most designers, could get away with. Its raked transom and stern rocker make it extraordinarily unsuitable for outboards, probably no accident.

The flare is nice. Besides making the skiff distinctively handsome, it provides the width to swing an 8’ oar. Since there is a continuous riser following the sheer, the flare gives you a place to sit or squat against when sailing; if you want to shift forward or aft of the center seat, one can perch on the flare and riser as kind of a narrow bench.

Pete didn’t give the skiff much freeboard. For rowing on the open Penobscot Bay, my friends, Sam and Susan Manning, raised the sheer on theirs several inches by adding another narrow strake. After work with a batten, they tapered the strake into the stem as if it were a rubrail, and added a piece to the outboard edge of the transom to match the height of the new sheerstrake. Amidships, the new sheerstrake pretty much hit the height of the oarlock blocks needed with the original sheer because of the low freeboard.

Traditional construction provides some maintenance challenges. There are a lot of different angles, planes, and nooks to sand and paint when it’s that time. That said, a good, sound interior paint job lasts many seasons, with maybe some attention to the chines where water can pool and the seat tops, worn by sun and use.

Culler left many construction details to the builder, so I expect that no two Good Little Skiffs are the same. Following the Chesapeake tradition in which he was schooled, he called for a tight-seamed cross-planked cedar bottom. It needs to swell tight before use, as the planks shrink when dry and the seams let light through—I use “boat blankets” and a hose. You can trailer the Good Little Skiff with a traditional bottom, but you’ll have to manage the swelling. Better is to use 1/2″ marine plywood in a continuous sheet instead of cross planking.

David Cockey

David CockeyWith the author aboard, the Good Little Skiff sits right on its lines with the transom just above the water’s surface.

This skiff, like most very small boats, is really sensitive to fore-and-aft trim. Pete drew in just one thwart, so when rowing with a passenger, the bow will aim skyward. It is a simple fix: add a removable seat forward of the rowing station; the seat just rests on the riser. Mine stows under the sternsheets when not needed. There is more freeboard forward so the second set of oarlocks can be mounted on the sheer without blocks to elevate them.

Culler assumed, I think, that the boat would be sailed by two, since the tiller can’t be reached from the amidships seat. For solo sailing I added a tiller extension that is about as long as the tiller. It is just right. With my weight on the center thwart the skiff is in good fore-and-aft trim, and sitting sideways lets me slide athwartships or move to the rail to respond to heeling.

I’ve reengineered the sternsheets to have a movable section in the center, which makes painting under the seat—something recommended by Pete—a less painful process. As it happens, you can lower that section down to rest on the stowed bow seat and use the space to hold your boat bag. The bow seat becomes a shelf to keep lunches and sweaters out of the bilge, a handy feature for a boat not equipped with floorboards.

As designed, the skiff has no stretcher to brace your feet against when rowing. I used to use the end of the short keelson to which the skeg was bolted. In the recommission, I tried a plank set on edge on the chines and braced it against the frames and, after some tapering and other tuning, it proved perfect.

I’d forgotten how much fun the Good Little Skiff is—as long as the water is suitable. You can move around in the skiff without it feeling uncomfortably unstable, something that can be a little more difficult in some of today’s lightweight and often twitchy craft. What it does well is proceed under oar and sail at an easy 3- to 4-knot pace, which is doing well for a boat with a hull speed of about 4-1/3 knots. It doesn’t like a chop. Rowing in a chop where the bow slaps into the waves is miserable. And the skiff is ill-suited to open-water whitecaps.

David Cockey

David CockeyThe loose-footed spritsail is equipped with a brail that can quickly furl the sail and the sprit against the mast.

Pete gave the skiff an ample loose-footed spritsail of 70 square feet. Rigged with a brail to bundle it up, it is simple to set and douse. It moves the boat well in light summer breezes, but when you start seeing whitecaps, if you are solo, you will need a reef. Like most spritsails, it is easier to reef when the rig is struck.

Sailing to windward against a 1- to 2-knot tidal current, my tacks take me straight across my river and back a lot but don’t make much progress. It is simple to brail up the sail, pluck the mast out of the step, and lay it down over the bow. Taking to the oars, I can make steady headway uptide.

One of the things I don’t think Pete realized is how well balanced the Good Little Skiff is. As long as there is not a sea running, you can straddle the center seat and sail it without bothering with a rudder: lean forward and to leeward and the boat turns upwind, flatten it out and lean aft to turn downwind. You can keep it straight running with a bit of windward heel. It’s so easy that I mostly don’t bother to bring along a rudder when sailing, and just take along my old sculling oar, setting it into the transom’s notch for a little help turning.

David Cockey

David CockeyThe skiff has good stability for standing while sculling over the stern. The boat’s heavy construction keeps it from wagging excessively.

And the Good Little Skiff sculls beautifully. Light dinghies and skiffs can be sculled, but they don’t have the weight and fore-and-aft resistance to keep them from being wagged by a seriously wielded sculling oar. There is plenty of stability to stand and lean into the oar. My old oar has a 4′ blade and a 10′ shaft which, like duck hunter’s oars, has some curve in it. As you scull, the oar blade digs deeper.

The Good Little Skiff does skiff stuff: poking along the river shore on a leisurely afternoon sail in a nice 10-knot breeze, checking out craft in a harbor, idling the tide downriver on a calm morning under oars to explore tidal shallows, lunching on a tide-revealed sandbar, then catching the afternoon breeze and turned tide to ride home. Pete’s Good Little Skiff is hard to beat. As Howland put it in his pamphlet about Culler’s boat: “A good skiff is a fine boat and for many uses no one has ever figured out anything better or ever will.”![]()

Ben Fuller, first curator of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, and past curator of the Mystic Seaport Museum and the Penobscot Marine Museum, has been messing about in small boats for a very long time. He is owned by a dozen or more boats ranging from an International Canoe to a faering.

Good Little Skiff Particulars

[table]

Length/13′ 6″

Beam/4′ 4″

Bottom beam/2′ 10.5″

Sail area/70 sq ft

Optional sail area/83 sq ft

[/table]

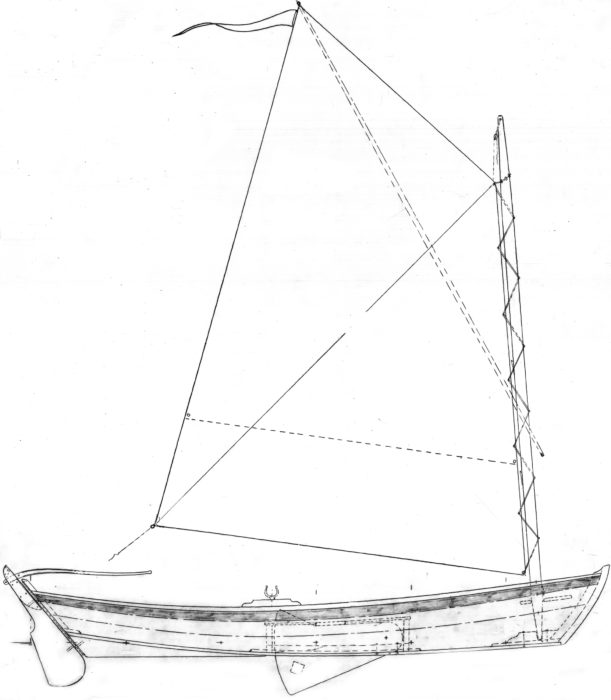

© Mystic Seaport Museum, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, Robert D. Culler Collection, SP128.5.

© Mystic Seaport Museum, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, Robert D. Culler Collection, SP128.5.Sail Plan and Construction Notes for 13’ Good Little Skiff by Robert D. Culler, 1 1/2” = 1’, 03/18/1971

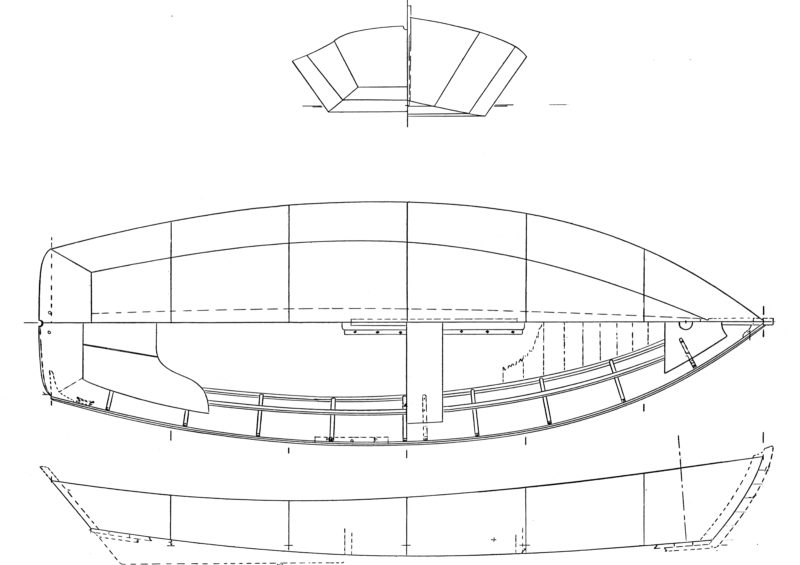

© Mystic Seaport Museum, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, Robert D. Culler Collection, SP128.5.

© Mystic Seaport Museum, Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, Robert D. Culler Collection, SP128.5.Lines and Construction for 13’ Good Little Skiff by Robert D. Culler, 1 1/2” = 1’, 03/19/1971

Plans for the 13′ Good Little Skiff are available from Mystic Seaport for $50. The two sheets include measured drawings and construction details.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Comments:

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.

Fine looking boat, sailed by an artist. Thanks for the notes on a good mess-about boat.

Hi,

In 2013, I had the good fortune to be in a wooden-boatbuilding class at the Lowell Boat Shop with 3 others; Graham MacKay was our very knowledgeable instructor. At the end of the 6-week build, there was a chance to row this relatively light and swift rowboat. A raffle was held for a chance to own this boat, but my name wasn’t selected. The lapstrake hull of the Good Little Skiff had enough rocker built into it to reduce drag. This class initiated my interests in traditional wooden small-boat building.

Finished up the fall doing skiff stuff with mine. First were some trips along the St. George on a real high tide. Poking along an oar’s length or so out, switching to the sculling oar as needed. These were trash trips and I came home with a filled skiff, getting at places that were impossible to get from land, and hard to reach by water. Mistake I made was that I wasn’t planning to do this so I didn’t have a contractor bag or boat hook. I did have boots. I reckon I pulled in a couple bag loads.

Then it was to head to a launching on a mirror-calm day of a new Australian-style Moth. Just enough air to sort the rig, but it flattened out again. Instead of carrying the 90-lb Moth back up a hillside, I volunteered to row it the mile or so around to the boat launch. It was so light that I barely felt it.

Now deciding if the skiff is my winter boat instead of the dory. Sure would be easier to clear the snow and ice out, but maybe not so good if the breeze kicked up a sea.

Why is the rear seat called sternsheets? I know what stern means, but how does “sheets” refer to a seat? Where did “sheets” derive from?

From Origins of Sea Terms, John G. Rogers, Mystic Seaport, 1985:

Stern sheets: A platform or seat in the stern of a small boat. The term sheet in this sense comes from the Old English skeat, a floorboard or platform in a boat.

Thanks for the education. I always assumed it was a reference to sheeting down to cleats on the boat’s quarters, just over top of the stern sheets. So you know… where you sheet, in the stern. Stern sheets.

Wonderful review, Ben. Such an adaptable boat. Would you share with us your rigging of the main sheet? You make it look effortless. And your lacing of the sail to the mast. How will that work when reefing? Reefing a spritsail has always been a challenge for me.

Hope you can bring your skiff to Mystic this June. Will be fun to compare with the one in the Boat Livery. Always enjoy your dockside talks.

Thanks,

Bill

Mystic was and is the objective of the rehab. Question right now is whether I’ll use the skiff as a winter boat.

Main sheet: Pete just swapped a single sheet from side quarter to quarter to get a nice lead. Indeed in some of his boats he put in kind of a thumb-cleat ladder which would work like a job sheet track.

I’m kind of lazy so I dead-end the sheet on one quarter, run it through the big grommet on the clew and then to a small turning block on a strop on the other quarter. There is friction in this system but it is good. Kind of like a ratchet block, helps you hold the sheet. If I need to fine trim just luff a little. I also have a half pin at the edge of the port stern bench which allows me to take a turn or use a slippery hitch. When I’m sailing in the center of the boat, I can also take a turn around the thwart and lead to a little wooden jam cleat at the aft end of the centerboard trunk.

David and Katherine Cockey were kind enough to launch their outboard to serve as a photo boat. Katherine did a nice job putting the boat in the position so that David could shoot. Many thanks.

Noted that I made a mistake with my Moth description: a New Zealand Moth, not Australian.

Looking at the pics, I do need to get a new set of oars made for the skiff: the ones I’ve been using for the skiff have the orange of my dory sheerstrake. They need to get some green on them. I like to do parallelograms as they are easy to do with some masking tape and don’t have paint on the tip or corners of the oars which I find gets distributed to the boat.

I take this article as an early Christmas present, as I’m currently looking into building the Good Little Skiff (or something comparable).

A few questions to the author or other experienced boat builders: The plans are originally intended for traditional solid-wood construction (clinker with cross planked bottom?). This method is probably not suitable for me, as the boat will be stored in the garage and only get wet once or twice a month (hopefully). Also, traditionally build, it will be too heavy (150 lbs?) for me to handle by myself.

So can this boat be done in clinker plywood? After reading a few books on the topic, I would say yes, but then, what do I know about boat building? Would 3/8″ okoume ply for the bottom and 1/4″ for the strakes be enough? I want to build a rowing-only version, so there’s probably less torsion to the hull. Would it be possible to keep the weight below 100 lbs? I need be able to drag the boat in and out of the water on the river bank close to my home.

Or should I forget about the Good Little Skiff and look for something else? I really love the aesthetics of the Good Little Skiff and I think it would fit my intended usage perfectly: relaxed rowing and exploring in protected waters, mostly alone, but sometimes with wife and kid, or maybe a friend. Another boat that I’m interested in would be Joel White’s Shellback Dinghy… any other suggestions?

Thanks for your comments.

Peter

I think that there have been a bunch of ply-bottomed GLSs built for trailering. I suspect that they have done 1/2″ ply, but I don’t know for sure. You might take a look at the scantlings of some of the skiffs that have been designed for ply use, and the same for the sides. Try Ian Oughtred and Chesapeake Light Craft designs. The GLS does have chine logs which make it easier to fasten those flared sides. If you want to do it in ply, do you expect to use mechanical fasteners or glue? If you do decide on glued lap, I’d still be inclined to put in enough framing to be able to support the full-length riser. Said structure stiffens things up nicely and lets you have a removable bow seat, makes installing thwarts and the stern sheets easy.

I reckon mine, soaked up, is under 200 lbs as I can muscle it around pretty easily. I have no problem pulling it up on a beach or onto the trailer.

I have built three Good Little Skiffs, all three in plywood. I use 3/8″ ply for the entire boat, and on two of the skiffs I also fiberglassed the bottom in epoxy. I used them in Puget Sound, where “beach” means smaller rocks to drag over and my original GLS, which was double planked on the bottom with 1/4″, had to have a new bottom after five years. I glassed the new bottom. I put hardwood hooks at the transom, between planking and inwhale, both sides, to take the mainsheet. It works a charm. I made my first sail out of a brown polytarp, but it was pretty ugly, so I made the second out of white polytarp. I eventually built a couple of sails out of canvas duck/boat drill. The cloth sails look better up close, but don’t work any better than the polytarp. Sprits’ls can be cut flat, so that does not matter. Consult Marino’s Sailmaker’s Apprentice. Building in plywood,, you can scarf both the bottom and the sides and have clean straight planks. You can also butt-block the sides at the seat, hiding it between two frames, but you will have to scarf the bottom to avoid a butt block there. With ply sides and the lovely flare, you do not even need frames at all. I put them in anyway, because it looks better. It also allows for the lovely inwale supports. For a handy and lovely craft, the only better one I have built and owned has been my 17′ faering beach cruiser, based mostly on White’s Shearwater. By myself, the GLS needs a trailer. With a rowing or sailing partner, two can easily carry the boat to water, and she will fit on my lumber racks for my little S-10 pickup. Complete plans for the boat are in the book Pete Culler on Wooden Boats. As to comparisons to White’s Shellback, the GLS is much easier to build, cheaper, and three feet longer.

Glad that you chimed in with the specs for a ply version. One of the things about plywood is that it makes these builds much more accessible to those without sawmill-grade lumberyard resources. I agree about the framing; the rise that it allows is real handy, except when its time to do some repainting.

Pete’s skiff was the first boat I built, back in the early ’70s. I still have letters from him that explained some of the details, as I was pretty clueless. Turned out to be a truly great little skiff. Rowed quite well and I can attest it was incredibly seaworthy in chop. Those highly flared sides really kept us upright in conditions we really shouldn’t have taken her out in. I wouldn’t mind building and playing with another one someday!