COURTESY of TOM KILEY

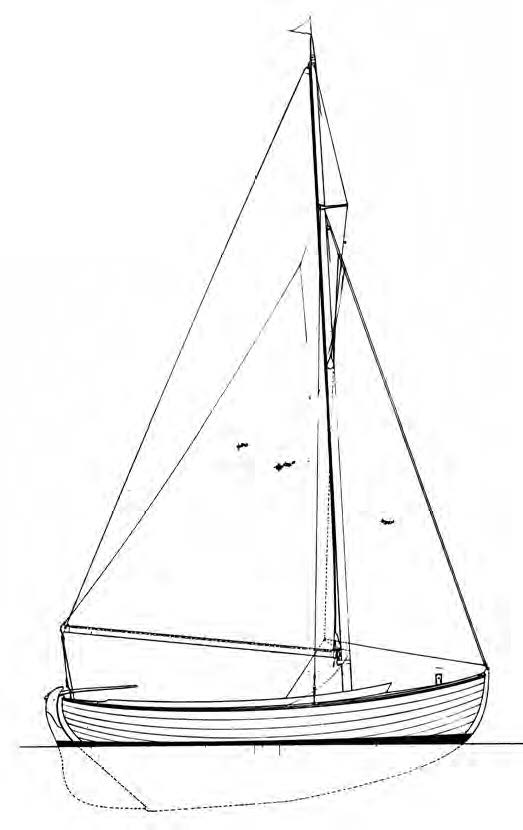

COURTESY of TOM KILEYAt only 15’ long, PRIMROSE is a commodious and seaworthy small yacht. Designer K. Aage Nielsen was

instrumental in introducing the double-enders of his native land to the United States.

Aage Nielsen mastered many different styles during his career in yacht design, but he never forgot the lovely shape of the double-ended hulls he grew up with in Faaborg, Denmark. He was largely responsible for bringing the style to North America, not only by adapting historic workboat shapes for pleasure boats but also by refining them in new ways. PRIMROSE, at just 15′ LOA and launched in 1936, is the smallest of his designs of this type.

Full-bodied, double-ended hulls would have sur-rounded Nielsen during his youth. He was 21 years old in 1925, when he emigrated to the United States to take a job with John G. Alden Company in Boston, Massachusetts. It was a golden age, when many talented young designers brought Alden’s ideas to fruition. Nielsen went on to work with his friend Murray Peter-son during the Great Depression and later in the Bos-ton office of Sparkman & Stephens, where he earned Olin Stephens’s highest respect. After World War II, Nielsen went out on his own. Throughout, he continued periodically to find inspiration in the double-enders of his native land.

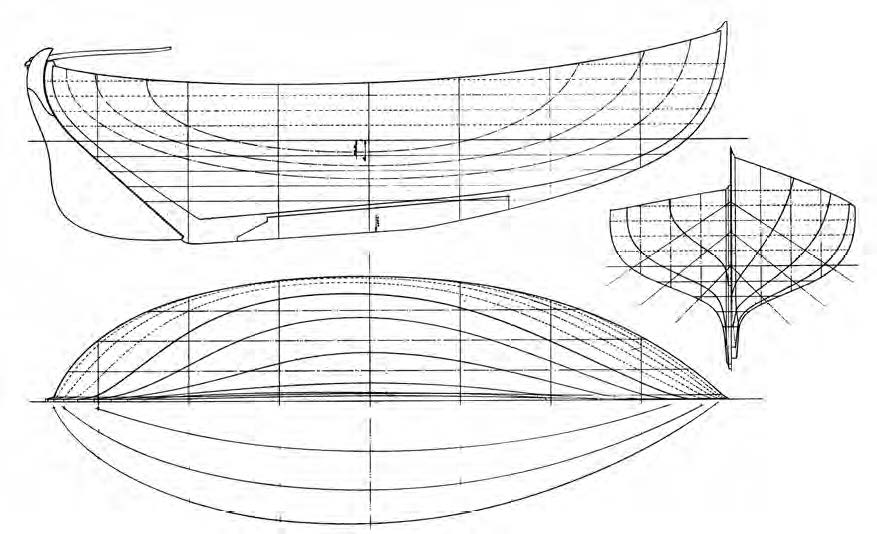

He designed a wide range of them, their sterns very nearly works of sculptural art. It’s a difficult shape to draw in two dimensions, and it has to be done right if the drawn shape is to have the right look when con-structed in three dimensions. But Nielsen had learned boatbuilding before going into design, having com-pleted a rigorous apprenticeship with roots in the European guild system. His knowledge of construction served him well as a designer throughout his career, and he held his builders to exacting standards.

Boats built to Nielsen designs tend to be highly prized by their owners. PRIMROSE is no exception. The owner of the unique little yacht—and yacht she is—is Tom Kiley of Camden, Maine, whose family has owned her since his father bought her in 1980. “This boat is a keeper,” he said. His children have grown up with the boat, and no doubt when the time comes his grandchil-dren will do the same. “It takes a half a pint of varnish, half a pint of white paint, and leftover bottom paint,” Kiley said, and he can take care of the usual seasonal maintenance himself. The boat has no engine or sys-tems, nothing to get in the way of sailing. How often does he sail her? His answer is simple: “Never enough.”

Kiley is a true aficionado of Nielsen yachts, having owned four of them over the years. In addition to PRIM-ROSE, he still owns SNOW STAR, a 36′ 9″ sloop of 1967. In the past, he has also owned two keel-centerboarders: WINSOME, a 1959, 35′ 9″ sloop; and STAR SONG, a 1965, 43′ yawl. He pays attention to his boats: PRIMROSE was extensively refit in the 1990s at Ballentine Boat Shop in Massachusetts, which among other things replanked her using white cedar to replace the original Philippine mahogany, with plank scarfs glued with epoxy to avoid using butt blocks.

COURTESY of TOM KILEY

COURTESY of TOM KILEYAs a traditional plank-on-frame hull, PRIMROSE is happiest spending the season on her mooring in Camden Harbor, Maine.

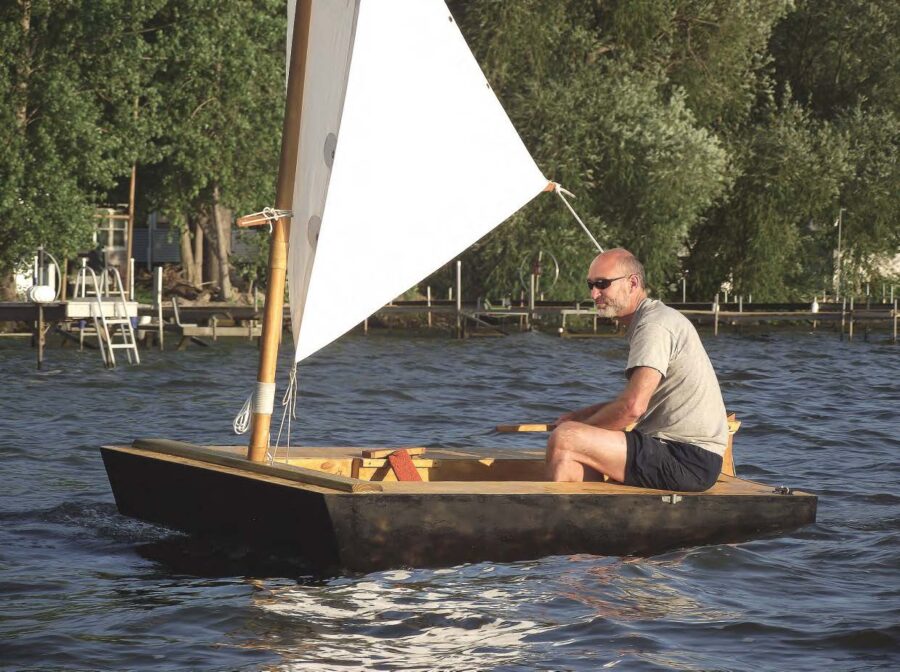

PRIMROSE rides at a mooring in Camden Har-bor, ready for any fine afternoon of daysailing. There, I caught up with Kiley and the boat in late July 2014. Kiley rowed us out to the mooring, and the familiar, unmistakable stern that Nielsen mastered so perfectly hove into view amid the crowded summer fleet. In a minute, we had cleared away the boom tent—a necessity, since the cockpit is not self-draining. In another minute, we had the jib hanked on, the marconi mainsail set, and we were ready to cast off.

In relatively light air, the boat moved very well, reminiscent of the best of the full-keeled small daysail-ers, boats like the widely admired Herreshoff 12 1⁄2. PRIMROSE has a waterline length of 13′ 5″, a foot longer than the Herreshoff, but like the 12 1⁄2, it has the feel of sailing a larger boat. Its 5′ 6″ beam makes the cockpit commodious and gives the boat very good reserve sta-bility. Like the 12 1⁄2 and its Joel White–designed cousin the Haven 12 1⁄2, PRIMROSE has a cuddy forward for stowage.

Kiley has two tillers to choose from, and most often he chooses the longer one so he can keep his weight forward, especially when sailing solo. The cockpit seats, now of teak instead of the original painted pine, are set higher aft than forward. This practical layout puts the helmsman a little higher than the crew, ensuring good visibility forward. A centerline rail on the floorboards provides comfortable footing when heeled over.

Kiley’s eye for a boat and attention to detail comes from a lifetime in yachts. He has a deep respect for Nielsen’s designs. On PRIMROSE, he points out some-what apologetically a stainless-steel shackle riding on the bronze horse traveler, saying he hasn’t yet found a suitable bronze one. But, the traveler itself is bronze, having replaced the original galvanized version. A mast break many years ago—before his family’s own-ership—was repaired by scarf-joining the sound Sitka spruce upper portion to a Douglas-fir lower portion, something he says Nielsen—a famous curmudgeon in his own times—would likely have frowned upon.

We tacked pleasantly out of Camden, the boat han-dling easily. The mainsheet leads to the helmsman’s hand, with no cleats to tempt anyone to make it off. Kiley has found it necessary to cast off the sheet imme-diately to get the pressure off the mainsail in strong gusts, which is important in a ballasted, open boat. “If we take water in here, we sink,” he said. “I have a canoe airbag I actually inflate, because if the boat fills up with water, it’s gone.” The fairly small jib tacks eas-ily, the sheets reeving through fairleads and coming aboard over the coaming, whose top edge is armored with lengths of half-round brass to resist chafing the varnish.

The tiller slips between cheek pieces at the head of the rudder, which is mounted on a very steeply raked sternpost, with the rudderhead sweeping forward to follow the profile of the stern. Such outboard rudders are typical of Danish double-enders. For a small boat, tiller steering is clearly the way to go, but for large double-enders Nielsen retained tiller steering only for NORTHERN CROWN, a 1956, 35′ 5″ sloop. For other larger yachts, he adapted the stern for use with wheel steering, with lines leading to a quadrant belowdecks. In these yachts, the rudder is set on a sternpost that is farther forward and not as steeply raked as in the traditional boats, making in effect a counter stern.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonSeated on the raised sternsheets, owner Tom Kiley has clear forward visibility from the helm. The mainsheet is never cleated off, allowing immediate depowering when needed.

PRIMROSE is a one-of-a-kind, built at the Simms Brothers yard in Dorchester, Massachusetts. (Nielsen found better success with a similar, but larger, 18′ 3″ double-ender with a small auxiliary engine, four of which were built, including FERN for author E.B. White.) Nielsen during his life was very particular about boats built to his plans. A boat such as PRIMROSE would be a challenge to get right, and Nielsen knew it. The difficult planking lines and hull shape aft require quite a lot of steam-bending and careful fitting. Hav-ing the shape look right depends entirely on building it right. Nielsen originally designed PRIMROSE to be lapstrake-planked, and she would be handsome that way; however, her client preferred carvel planking.

Nielsen always favored wood construction, shunning the industry’s move to fiberglass. He insisted on person-ally supervising each construction. By the time he died in 1984, he felt that the kind of work he demanded was becoming a thing of the past, and he stipulated that no further boats should be built to his designs. In many ways, it was an unfortunate choice, at an unfortunate time. In his final years, a resurgence in wooden yacht construction ushered in a new golden age, both in tra-ditional construction and in “composite” construction using wood veneers and epoxy to make cold-molded hulls. His plans are not generally available for use in building new boats of any kind.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonPRIMROSE was largely reconstructed at Ballentine Boat Shop in the 1990s, but much of her gear is original, including the Merriman Brothers bronze roller-reefing fitting for the main boom.

However, in the course of the production of the biography Worthy of the Sea: K. Aage Nielsen and His Legacy of Yacht Design (Tilbury House, Publishers, and Peabody Essex Museum, 2006), his family decided to pay homage to his legacy by authorizing limited permission for new construction. Nielsen for much of his career favored two yards: Walst-eds Baadevaerft in Thurø, Denmark, and Paul Luke in East Boothbay, Maine. Walsteds still builds in wood, but Luke turned to alu-minum in the 1970s. Following Nielsen’s own pattern, new construction can now be done at Walsteds (www.walsteds.dk), or Rockport Marine in Maine (www. rockportmarine.com). The latter came into play because Rockport’s owner, Taylor Allen, cares not only for his own double-enders NORTHERN CROWN and FERN but also about a dozen Nielsen yachts for custom-ers, the largest single concentration of Nielsen yachts anywhere. Someone looking for a new boat to the PRIM-ROSE design, therefore, could have a boat built professionally in the United States or Europe.

A classic yacht seems to transcend its own times. Sailing on their own or in regattas, Nielsen yachts still hold their own, in appearance and handling. “I have a great regard for that, as a sailor,” Kiley said. “I look at the design of HOLGER DANSKE [a 1964 double-ended ketch, 42’6″ LOA] or STAR SONG, and I think, wow, that was such a long time ago, and to get it so right so early, on the first try, was unbelievable. The tweaking, the little things, have changed it. They haven’t made it better. Things like self-tailing winches, and epoxy—those aren’t my ideas, that’s just staying current. But boy, to change that boat? How to make it better? I don’t see how.”

PRIMROSE stands as proof that Nielsen put as much of himself into his small boats as his large ones, and she is as timeless as any of them.

For more information about the construction of the Double-Ender 15 and other designs by K. Aage Nielsen, contact Rockport Marine, www.rockportmarine.com; or Walsteds Baadevaerft, www.walsteds.dk.

PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM/K. AAGE NIELSEN COLLECTION

PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM/K. AAGE NIELSEN COLLECTIONPRIMROSE

Particulars

LOA 15′ 1″

LWL 13′ 5″

Beam 5′ 6″

Draft 2′ 3″

Sail Area 133 sq ft

Displacement 1,720 lbs

Ballast 500 lbs outside

200 lbs inside

PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM/K. AAGE NIELSEN COLLECTION

PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM/K. AAGE NIELSEN COLLECTIONK. Aage Nielsen drew the plans for the Double-Ender 15 in 1935. She was originally intended for lapstrake construction, but the only hull known to have been built under Nielsen’s supervision—PRIMROSE, built by Simms Brother in Massachusetts in 1936—was built carvel, or smooth-skinned. Her full-keel hull form is directly inspired by the workboats Nielsen knew in Denmark during his youth. In adapting the

type for pleasure use, he paired a refined version of the traditional hull form with a modern fractional marconi rig, giving the small yacht comfortable seating and excellent performance for daysailing.

Nielsen, a masterful draftsman who was trained in construction, was known to be a stickler for personally overseeing the boats custom-built to his designs. Although new boats can be built by permission at Walsteds Baadevaerft in Denmark and Rockport Marine in Maine, his plans are not available to others for construction.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.