Lance Pamperin

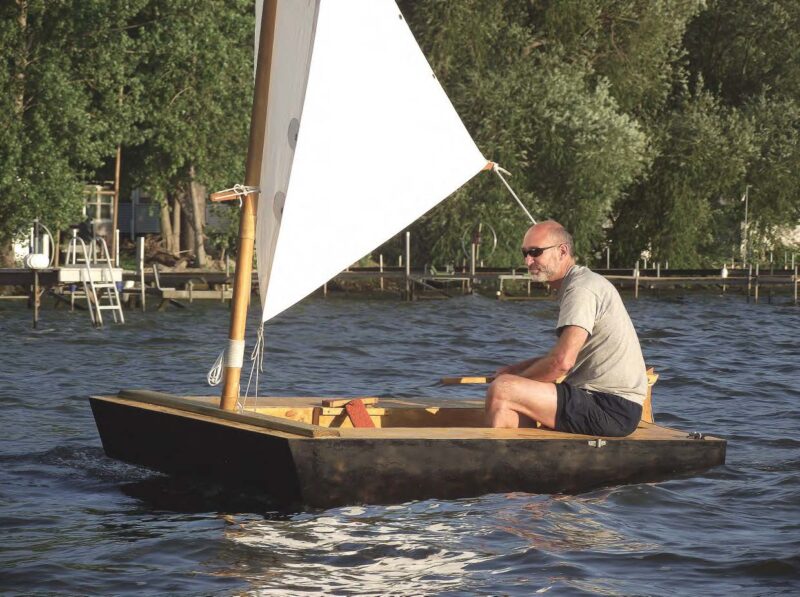

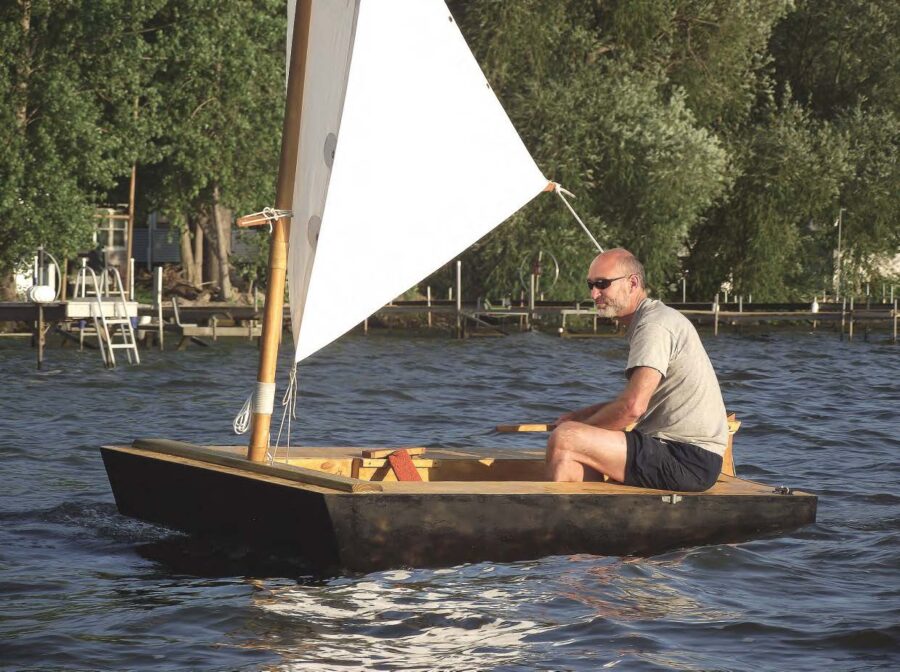

Lance PamperinA sandbox with a sail? The Puddle Duck racer may be humble in appearance, but it gets people on the water quickly for satisfying sailing.

It’s easy to be dismissive of the Puddle Duck Racer when you first see it. I usually describe the slab-sided 8′ × 4′ boat as a sandbox with rocker, a description that’s not entirely tongue-in-cheek. And yet, among its builders, who proudly refer to themselves as Puddle Duckers, this boxiest of all box boats has achieved a degree of popularity that is difficult to understand—until you try sailing one. The truth is, despite their boxy, unsophisticated looks, Puddle Ducks are pretty darn fun.

Of course, not everyone is able to suspend judgment long enough to make this discovery, something that Puddle Duck designer David “Shorty” Routh is well aware of. “They kind of look at it and say, ‘That’s not a real boat,’” he admits. But the Puddle Duck’s ultra-simple appearance is quite purposeful. “Really, I’m trying to pull in new people to get them to go in the direction of building wooden boats,” Routh explains. “The Duck is kind of like the free candy you give out to get people addicted. It had to be very unassuming looking, so anyone would look at it and think, ‘Yeah, I could probably build something like that.’”

The Puddle Duck succeeds brilliantly on that score. It’s probably not absolutely the easiest boat in the world to build—hulls with at least some flare can actually come together in the shop a little more easily—but that doesn’t matter. What matters is that to someone who has never built a boat before, someone intimidated by curves and bevels, the Puddle Duck looks simpler than other boats. And its flat-bottomed glue-and-screw construction does make it a very simple, fast build. When I talked my brother into building hull No. 892 for his kids, he was able to finish it in just five evenings, spending well under $200 (we reused the rudder, daggerboard, mast, and standing lug rig from another boat).

Tom Pamperin

Tom PamperinWith a buoyancy chamber built into each side of the boat, a Puddle Duck is easy to right after a capsize.

David Routh has no formal training in boat design, but he has spent a lot of time sailing and racing, and he knew what he was after when he created the Puddle Duck Racer in 2003: a way to get more people having fun sailing without needing to spend much money. But he wanted something more formal than the typical messabouts he started attending in the 1990s, which he says were “like a bunch of cats wandering around.” What he needed was a cheap, easy-to-build racing class that would provide an excuse for people to actually sail together, instead of just walking along the beach admiring each other’s boats. The Puddle Duck was his answer.

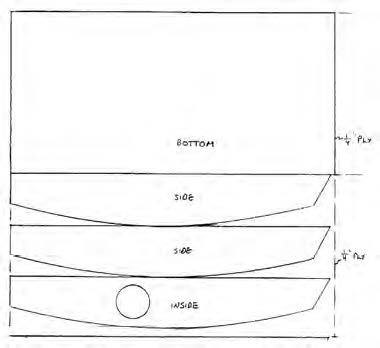

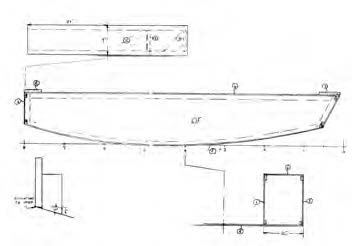

Routh describes the Puddle Duck as a developmental one-design class. The lower 10″ of each hull must be identical, with the same beam, length, rocker, and vertical sides. At official Puddle Duck events, each hull is measured to make sure it is class legal (a ¼” builder’s tolerance is allowed, and hulls that fail are allowed to compete with a penalty). Everything apart from the hull, though—rig, rudder, foils, sheer, superstructure (yes, there have been Ducks with usable cabins), and interior layout—is fair game for experimentation.

And while the Duck’s basic shape looks crude, there’s more going on with that boxy hull than might be immediately apparent. The rocker is more extreme at the ends, but flattens out in the middle—an attempt to blend the characteristics of a displacement hull and a planing hull. As a result, the boat sails better than it seems to deserve, reaching speeds up to 6 mph off the wind without too much fuss. The fastest recorded Ducker so far is Kenny Giles, who has hit 9.2 mph by GPS, using a 59-sq-ft leg-o’-mutton rig on a windy day.

“I really like the idea of having your building skills be part of the competition,” Routh says of his rules, which attempt to strike a middle ground between the arms race of open-class racing and the tight strictures of one-design classes. “It’s not about the limitations of the rules, it’s about the creativity of everything else.”

As a result of the class’s intentional openness, each Duck is laid out a bit differently within the basic shared hull shape. But it’s the rig where the developmental aspect of the class is most obvious. I’ve seen gaff-sloop Ducks, leg-o’-mutton Ducks, balance-lug Ducks, Chinese lug Ducks, lateen Ducks, standing-lug Ducks, sprit-sail Ducks, Ducks with repurposed windsurfing rigs, and one Duck rigged as a staysail cat. Routh has heard of even stranger rigs: wingsails, biplane rigs, and even a variant of the Micronesian-style proa rig described by writer and wild food forager Euell Gibbons in his book The Beachcomber Afloat.

Tom Pamperin

Tom PamperinWhen sailing off the wind, a Puddle Duck feels luxurious to its solo skippers.

Like most unballasted dinghies, the Puddle Duck should generally be sailed as flat as possible, some-thing its wide flat bottom makes a little more automatic than it would be with a more sophisticated hull shape. But the Duck’s rocker makes it extremely sensitive to fore-and-aft trim, which makes it an excellent boat to learn on—Duck skippers are punished for their mistakes in very obvious, yet relatively benign ways. Keep your weight too far forward and the bow transom will dig in deeply, the Puddle Duck’s characteristic “pig rooting” behavior. With your weight too far back, you’ll bury the transom and feel the speed drop off dramatically. Someone new to sailing, or new to dinghies, will quickly learn that small boats demand constant weight shifts and awareness of trim for optimum performance, a mindset that’s not easily learned by crewing on heavily ballasted keelboats.

With its flat bottom, and a length-to-beam ratio under 2, the Puddle Duck’s initial stability is quite high—another feature that beginning sailors will appreciate. And most Ducks are designed and built with two large buoyancy chambers (fore and aft, or one on each side), making the boat easy to right after capsizing. The use of a single externally mounted leeboard, probably the most common choice, allows builders to avoid the complications of daggerboard cases and pivoting centerboards if they prefer. Plenty of Ducks use daggerboards and centerboards, though, often set into a side buoyancy tank to save legroom.

Tom Pamperin

Tom PamperinThe Puddle Duck’s popularity has drawn serious racers to a growing number of competitive events.

Despite its awkward appearance, the Puddle Duck is a surprisingly comfortable boat to sail when it’s not bashing its way through the waves—its lack of streamlining and short waterline can make fighting a steep chop seem like riding in an unbalanced washing machine. Off the wind, though, or in flat water, a Puddle Duck feels luxurious. After his first sail in Duck No. 892, my brother described it as “an old man’s boat”—the side buoyancy tanks offer extremely comfortable seating, and the off-center daggerboard leaves plenty of room to stretch out. With a designed displacement of 630 lbs, it could easily take two adults without dragging the bow or stern. A better option, though, would be to build a second Duck. It’s such a simple design that there’s little excuse not to.

But, simplicity aside, the real genius of the Puddle Duck is the childlike innocence it brings to sailing. Tearing along at 3 knots as if possessed by a wide-eyed eagerness to seek out the unlikeliest, most ridiculous way to do things, the Puddle Duck is a boat designed for play. I’m struck by the design’s utter lack of pretension. It’s a bit silly—and at the same time endearingly naïve—that a boat with a theoretical hull speed just over 4 mph would bother to register for a Portsmouth Yardstick rating (with a handicap of 140, it’s the slowest boat on the list), but there are serious racers among the Puddle Duck crowd. On the other hand, I was able to borrow a Puddle Duck at the 2012 World Championships (the first races of any kind that I ever competed in) and place seventh overall—far behind the leaders, but having a good time all the way.

Tom Pamperin

Tom PamperinPuddle Ducks have made some serious voyages-incompany for an 8’ boat. In 2014, 12 of them finished the grueling five-day Texas 200.

Other Puddle Ducks have been used for voyages more ambitious than simple round-the-buoys racing. Completing the five-day Texas 200 in a Puddle Duck, for example, has become something of a rite of passage—12 Duckers finished the event in 2014, a record number. Upping the ante considerably, Scott Widmier attempted the 300-mile WaterTribe Everglades Challenge in his EC DUCK in 2012, reaching as high as fifth place in his class (sailing monohulls) before high winds and bad weather forced him to abandon the race (conditions were so challenging that only two mono-hulls managed to finish). Like a Chihuahua challenging a Rottweiler, the Puddle Duck just jumps in and goes at it, without seeming to realize it might look a little silly to observers. Or maybe it just doesn’t care.

Free Puddle Duck plans are available from the website www.pdracer.com/free-plans/, or from Jim Michalak at www.duckworksbbs.com/plans/jim/catbox/index.htm. Learn more at www.pdracer.com.

Tom Pamperin

Tom PamperinThe Puddle Duck is not a strict one-design; rather, it’s an open class, meaning that boats must be designed within broad measurements rather than be identical. Here we see the Catbox design, which you can download, along with others, at www.pdracer.com/free-plans.

Tom Pamperin

Tom PamperinPuddle Duck Particulars

LOA 8′

Beam 4′

Sail area 69 sq ft

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.