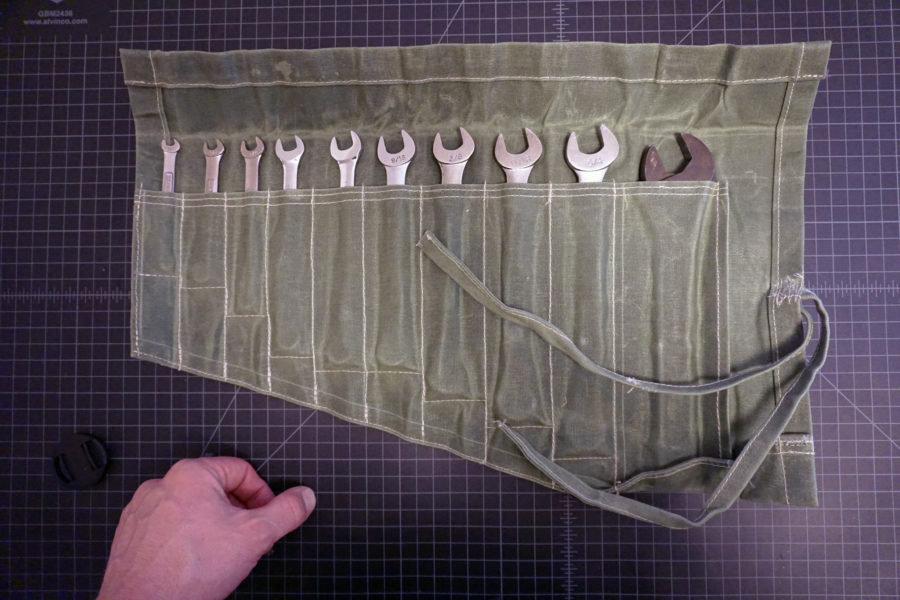

Wooden boats come with their fair share of hand-sanding, whether it’s smoothing wood surfaces or between coats of varnish or paint, so it pays to extend the useful life of sandpaper. In my experience, it’s not the abrasive particles that wear out. I’ve looked at the grit of new and well-used sandpaper through a strong magnifying lens, and there’s not much difference: the grit outlasts the paper. Some of the newer, more expensive sandpapers have thicker backing materials, but they still can be torn. Once a small tear starts on the edge, it’s likely to continue across the sheet. The paper backing of a piece of 150-grit doesn’t hold folds well and can roll, damaging the abrasive coating. The same 150-grit sandpaper with duct-tape backing doesn’t roll and keeps its shape. The sharp, undamaged folds can more effectively work into corners. Photographs by the author

Photographs by the author

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.

Comments (6)

Leave a Reply

Stay On Course

I’ve been building keel patterns for Mars Metal in Burlington Ontario for almost 28 years, I use a 17″ X 21/2″ air file (like they use in auto body shops), if I don’t put at least two layers of duct tape on the sheets first, the air file tears them apart in about 15 minutes. On the larger patterns I’m sanding F 26 fairing compound for hours at a time and can usually get through one side with a single sheet.

Cheers, Ken

Great suggestion. I’ll be making the masts and spars for the boat I’m currently building (Doug Hylan’s Siri) and will certainly use this method for final shaping. I agree that old sanding belts are less than satisfactory.

By the way, just a shout out in support of Mars Metal. I recently received the ballast keel for Siri from them – excellent work, I heartily recommend them if you don’t have the facilities to cast your own.

Andrew

Thanks !

I would never have thought of doing that, what a great idea!!

Good advice. I have already experimented with this sanding system when I build the oars for Venetian rowing which are about 3.5 meters long

Great idea. I’m making my first pair of oars and was wondering how the sandpaper would stand up to the job – I’ve got heaps of duct tape lying around from boats, so I will definitely try this trick!