I built this cabin on a slope above the South Fork of the Sauk River in 1980. Most of the materials I used were salvaged from demolition jobs I did or purchased at junk yards. The aluminum sheets I used for roofing were offset lithography plates for a book about the Umpqua National Forest. It made for interesting reading while I nailed them on the roof. The main floor was devoted to shop space; I slept in the attic above and cooked on the workbench.

Building my sneakbox, LUNA, in the winter of 1984 in a shop without electricity wasn’t as hard as it might seem. While I was living on an old mine claim in Monte Cristo in the heart of Washington’s Cascade Mountains, I used a Tote Goat trail motorcycle to power a makeshift tablesaw and a gas lawnmower engine for my bandsaw.

The view from the shop was filled with a mountain range that rises steeply about 3,000′ above the riverbed. During the winter, the county stopped plowing the road 14 miles away and I had to ski out to get supplies and ski back uphill with a heavy backpack. It was brutal work in fresh snow when I had to break trail. If I would have had an emergency during the winter, I’d have to get myself out or hope for a weekend snowmobiler to help me. There were no cell phones back then.

Once I had all the red cedar ripped into planks for cold-molding, hand tools were all I needed and what I preferred to use even if I’d had power to run electric tools. I didn’t work long hours after dark, and battery-powered lanterns and candles provided enough light.

For my sneakbox, I used a traditionally built design from Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft and adapted it for cold-molding to make the boat lighter and suitable for the short lengths of red cedar I had salvaged. I cut the molds from the particle-board side panels of video arcade machines. I’m seated at the far end of the shop.

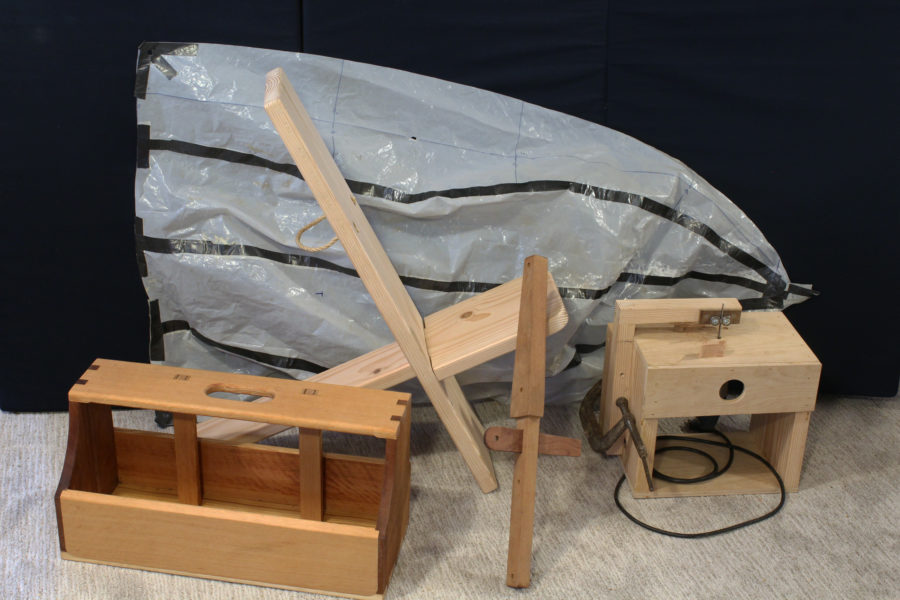

I milled the 1/8″ planks from a red-cedar driftwood log I hauled off the beach near my home in Edmonds, Washington. Here, the first of the hull’s three diagonal layers has been applied to the port side with the staples driven through salvaged packing straps to ease the removal of the staples. In the back left is the plywood-faced Gilliom bandsaw I built from a kit and powered with a Briggs & Stratton lawnmower engine.

Heat for curing the epoxy was provided by a woodstove, which worked very well even in the dead of winter when the shop roof was thickly frosted with snow. I’d fire it up for a gluing session and have the shop heated up into the 90s before I epoxied and stapled a set of planks in place. The fire would die down and the shop would cool overnight, but it never dropped below 50 degrees, even when it was freezing outside.

After I finished cold-molding the hull, I suspended it from the ceiling and went to work on the deck. Here, the first of two layers has been stapled to the building-form stringers with scraps of planking to make them easier to remove. I saved the best of the planking for the final layer of the deck. I had kept the planks stacked in the order I’d sawn them so I could bookmatch pairs for a symmetrical pattern on the top layer of the deck.

After I had laminated the hull and deck, I joined them together with a sheer clamp. There was no other framing in the hull, so I set out to fiberglass the deck and hull to the clamp on the inside to strengthen the union. That task was easy enough in the cockpit, where I could just reach through the foot-locker-sized opening and apply the ’glass and epoxy, and not so bad in the stern where the transom provided enough space for me to move around and get the ’glass-taping job done. The bow was another matter. The space between the deck and hull tapered from about 14″ at the cockpit to the 1-1/2″ sheer clamp. There was just barely enough room for me to work.

A votive candle in a tuna-fish can provided the light I needed to work on the interior of the assembled hull. (I took this photo in the bow of the finished boat.)

I put on a pair of gloves, cut fiberglass tape to length, and mixed up a batch of epoxy. To illuminate the space in the bow, I lit a votive candle, set it in an empty tuna-fish can, and pushed it ahead of me as I crawled in. I loaded a disposable brush with epoxy and went to work prodding the ’glass tape into place on the port side. It was a tight squeeze, and I could only reach the tip of the bow (a distant 5′ 6″ away from the cockpit opening) by holding the very end of the brush handle. I backed up, rolled over, and went to work on the starboard side. The daggerboard trunk, set on the starboard side of the cockpit coaming, gave me less room to work and pinned my left arm against my side. I managed to get all but the last few inches saturated with epoxy and pressed in place against the sheer clamp. To get the reach I needed to finish the job, I squeezed myself forward a few more inches. As I dipped the brush into the dish of epoxy, I smelled something burning, slightly acrid like bread smoking in a toaster. I didn’t feel or hear anything unusual, but it was easy enough to tell that I had lunged into the votive candle and set my hair on fire.

I couldn’t do anything with my left hand. It was pinned tight. The glove on my right hand was dripping with epoxy and the brush was stuck to it. For a moment, I feared that liquid epoxy might be flammable, but I had to take the chance that it wouldn’t catch fire and set the whole boat ablaze. I flicked off the brush and patted my head as I writhed out of the bow. That put the fire out, but my hair was coated with epoxy.

I had warmed the shop to cure the taping job, but I certainly didn’t want to hasten the cure of the epoxy on my head, leaving an unsightly and permanent coiffure. I closed up the shop and walked through the snow to my cabin, a dozen yards away. Brushing the epoxy out would only have spread it. I squirted the best part of a bottle of shampoo on top of my head and worked it in, trying to get every strand of hair separated. When I could run my fingers through it, I put a plastic produce bag over my hair and left it there for a couple of hours while I tended to dinner, dishes, and getting ready for bed. When I took the bag off, I was able to run a comb through my hair and pull out the gummy shampoo-and-epoxy gunk.

After the hull was sealed enough to endure a little weather, I put in on a sled made from skis and towed it by snowmobile to the plowed road. I took advantage of an opportunity to move to a log cabin on Lopez Island in Washington’s San Juan archipelago. Moving below the snow line made getting groceries a whole lot easier.

In November of 1985, I drove the sneakbox to Pittsburgh and embarked on a winter cruise aimed at Florida. Here I’m in the first mile of the Ohio River, looking over the stern at downtown Pittsburgh with the Allegheny River flowing under the bridge at left, and the Monongahela under the bridge at the right.

The following winter, I launched the sneakbox on the Allegheny River on the outskirts of Pittsburgh. Over the following two-and-a-half months and 2,400 miles I rowed downriver to New Orleans and then sailed and rowed the Intracoastal Waterway to Florida. I had some miserable times and some frightening moments, but the cruising was certainly less dangerous and more romantic than boatbuilding by candlelight.![]()

This issue goes out with special thanks to Delaney Brown, who was instrumental in producing the past two years of Small Boats Magazine.

You were a resourceful and intrepid young lad Chris! Impressive.

Not knowing a lot of folks who boatbuild off the grid, I’m imagining that few of them would take the time to bookmatch the deck planking. Quite the story, and only the beginning for that sneakbox.

Huzzah,

Skipper and Clark

Inspiring! I really enjoy your stories.

I loved your story even though I think you may be just a bit crazy! Oddly enough, I grew up in Edmonds and now live on Lopez Island. Would love to see your boat sometime if you’re still up here!

Thanks, Lyn. The sneakbox and I moved from the cabin we rented on Hooterville Lane and we’re now in Seattle.

Have to take my hat off to you. Well done. I know how it feels applying glass and epoxy in restricted spaces having built a trimaran.

Sounds like you have had an amazing life. I wish I would have discovered small boats before I discovered cars.

Good work. Fiberglass scares me—more about screwing it up than about health issues. Did you have to read the litho plates backwards?

The plates were for offset lithography so they were right reading. They get inked and then transfer the ink to a rubber “blanket,” which is reversed, and the blanket prints the ink on paper.