Kmehlsphotography.com

Kmehlsphotography.comOwing to her light weight and refined shape, Harrier is exceptional under oar or sail. Designer Dias rows the boat here with author Bennett.

RAN TAN was built to Tony Dias’s Harrier design, which is, in part, a development of an earlier design of his, Marsh Hawk. But Tony will tell you that Harrier was drawn specifically for Ben Fuller, for campcruising, with a good deal of input from Ben himself. A small-boat aficionado, Ben comes from a background of rowing boats and sailing canoes—he has an interest in just about any small boat that rows and sails fast, and he is unafraid of high-tech. But he also knows and appreciates tradition better than anyone—he has been curator at Mystic Seaport and Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, and is now curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine. He came to Tony with his ideas, and together they created the Harrier double-ender.

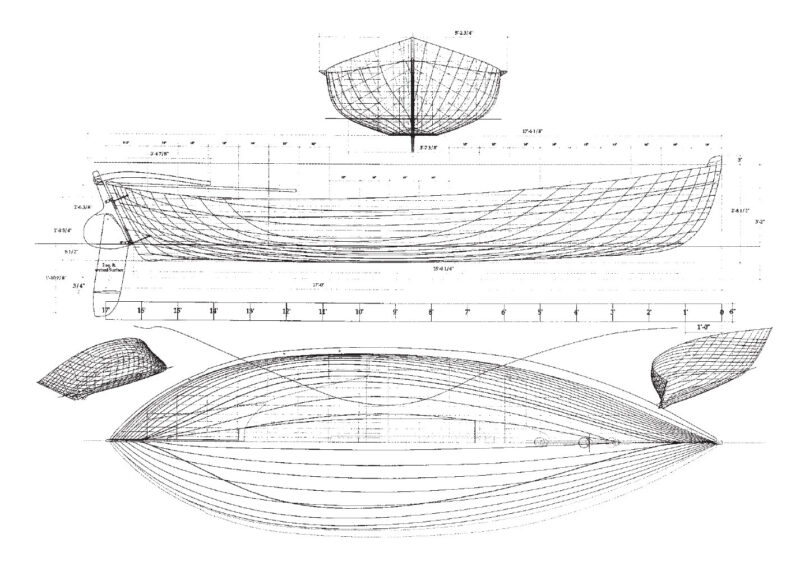

Tony takes up the story: “We started with Marsh Hawk, a round-bottomed double-ender with an external keel, but Ben wanted a boat that would beach easily. We were both very interested in the plank-bottomed wherry shape—there’s a Piscataqua wherry in the collection at Mystic; it reminds me of working boats I’ve seen in Portugal. So, our idea was to take Marsh Hawk, chop off the keel, flatten out the bottom like a wherry. In a Banks dory or a mackerel seine boat, the shape, and therefore the way the boat behaves, makes you feel at home, even though you’re in an open boat in rough water—that’s what I think we were after.”

At Rockport, Maine, we have loaded two pairs of oars into the boat and Tony is laying the daggerboard across the aft benches to act as a temporary rowing thwart. “With two people rowing you want an aft thwart, but you don’t want a permanent seat cluttering up the cockpit for sailing—the daggerboard is the perfect width and length for the job.” We pull away from the dock and immediately are up to speed, tracking easily through the harbor, the water chuckling against the lapstrake hull. We sight-see for a while but are anxious to get sailing and return to the dock to step the mast and raise sail.

Kmehlsphotography.com

Kmehlsphotography.comA high-peaked, fully battened mainsail set on carbon-fiber spars gives Harrier great power and stability. The mizzen balances the rig and adds maneuverability to the boat’s many virtues.

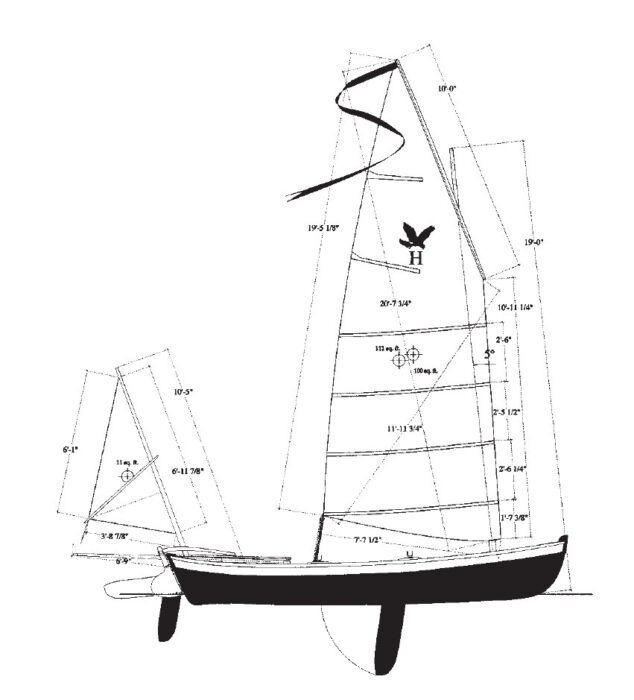

The Harrier carries a standing-lug yawl rig, high-peaked and fully battened in the main—an eye-catching blend of old and new technology. For years the lug rig was overlooked by all but European working-boat enthusiasts and designers of small sailing dinghies looking for a simple rig that could be used by children, required minimal standing rigging, could be stored within the boat’s own length, and was not aspiring to any form of “high performance.” Then came the Nigel Irens designed ROXANNE— a slippery 29′ 6″ yawl with a high-peaked standing-lug main carried on an unstayed carbon-fiber mast. “That rig, and its performance, fascinated me. For Harrier I originally drew up three or four different rigs with wooden spars, but it seemed only natural to use carbon fiber. Ben isn’t afraid of carrying sail, so isn’t concerned by a big, tall rig, and we found that if you use carbon fiber, which reduces weight aloft, you really don’t need to reef sail if you’re prepared to be athletic about it. You can reef if you want to, but the boat isn’t overpowered by the rig.”

There are other interesting features in the mainsail: the tack is low on the mast, the clew higher, and so the sail is self-vanging; there is a highly efficient downhaul to control draft; and in the lower part of the sail there are full-length battens giving stiffness (especially just above the foot) without the disadvantages that come with a boom. The battens, however, are a “work in progress.” The right level of stiffness is crucial: it has to be stiff enough so that when you’re off the wind, it doesn’t belly off like crazy and create too deep a pocket, but at the same time it has to be limber enough not to totally flatten when you’re close-hauled. As for the mizzen, it is a diminutive jib-headed spritsail that helps balance the rig, keeping the load on the helm lighter, and as Ben was to later point out, keeps the boat’s bow into the wind when reefing or at anchor. But it has uses beyond the usual: “Ben’s interested in camp-cruising, and you can use the mainmast as a ridge-pole for a tent awning—you lay the heel down against the stem and tie the head up on the mizzenmast; you almost have standing headroom in the stern.” And, as Tony was to demonstrate later, it is the perfect backrest for the idle skipper.

The joy of the carbon-fiber mast becomes apparent the minute you rig the boat. One reasonably fit person can lift the mast, one-handed, and stand it through the mast thwart into the step—and that’s all there is to it. To raise the sail there is just the one halyard counter-tensioned by the downhaul, and thanks to the boomless foot, the sail can be raised with the wind coming from any direction.

With two adults aboard, the Harrier seems bigger than her 17’6″ by 5′, and despite her lightweight construction (6mm plywood planking and a hull weight of about 200 lbs) she feels stiff and stable. Tony tells me that at the 2007 Small Reach Regatta on Eggemoggin Reach, Maine, they had three on board. “It was great—one person sits up forward, one amidships, and one right aft. With the boat more heavily loaded, it does make sense to reef down for a drier ride and less strain on the boat and the rig. When the boat’s lightly loaded, she’ll just go faster in stronger air and ride higher and drier.”

We have sailed away from the landing and are picking up zephyrs across the harbor. We are without the mizzen, for we have forgotten the boomkin. In this configuration, RAN TAN is tricky to tack in the light airs, but she will respond to, on occasion, a momentary backing of the mainsail. Tony demonstrates the boat’s stability by standing at the helm and shifting his weight as if on a surfboard; I settle comfortably on the center thwart.

Kmehlsphotography.com

Kmehlsphotography.comBen Fuller, whose vision gave rise to the Harrier design, sculls the boat at Rockport, Maine.

When Ben returns with the boomkin, we reach back to meet him and set full sail. RAN TAN is in her element. We run, wing-and-wing, down the harbor, Tony dipping beneath the mainsail every so often to check his path, me tucking lines out of the way, stowing extra clothes beneath the foredeck, and thinking about the options for sleeping aboard—on the flat floorboards either side of the daggerboard case (the center thwart is removable), or up on the seats with an infill for the aft cockpit. As we near the harbor mouth, we turn close-hauled and catch one of the few big gusts of the day. RAN TAN heels to the wind, seems to take a big gulp, and then comes back; never once do you get the feeling that she might just keep going. I was sorry there was not more wind, as it would have been fun to sit out on the wide side-wales and hike out. Tony concedes that, as with any unballasted boat, it is possible to capsize her, but even if the boat is swamped the flotation bags will keep her floating with the water level just below the top of the daggerboard case so you can bail it out.

We switch positions. I quickly become used to the tiller arrangement—not quite a “push-pull” in the Scandinavian sense, but with a rigid elbow and tiller extension that works conventionally—though with a dog leg to get it around the mizzen—and learn that she is remarkably responsive to the helm. We dip beneath sterns and shoot across bows as we pick our route through the moored boats back up the harbor. And as the occasional gust raises our speed, so we carry our way ever closer to the wind.

It is lunchtime. We head for a sandy beach on the seaward side of the town landing and, as we approach, raise the daggerboard. With no crew and no board, RAN TAN draws about 6″; even laden, we manage to run far enough up the beach that I can disembark without getting my feet wet. The tide is falling so we leave RAN TAN where she is, moored to a low tree branch. Some time later we will return to slide her down the beach on a couple of rollers and pull away from the little cove under oar. It has been a fine introduction to the boat—one that has left me hungry for more—and when I hear that RAN TAN will again be at the Small Reach Regatta later in the summer, I am delighted to think that I may get to try her in different conditions.

Harrier Double-Ender Particulars

LOA 17′ 6″

Beam 5′

Draft 6″/ 3′ 6″

Weight, (unladen) 200 lbs

Weight, (laden) 250 lbs

Designed by Tony Dias

Prototype built by The Apprenticeshop, Rockport, Maine

For plans information, contact Antonio Dias by e-mail at [email protected].

Antonio Dias

Antonio DiasExceptional detail and artful rendering are hallmarks of Tony Dias’s design style.

Antonio Dias

Antonio DiasWhile Harrier is not a simple boat to build, her plans are exceptionally well detailed and within the reach of a beginner with aptitude.

Possibly the only row sail boat out there with a toe strap. Wide external decks make hiking pleasant and let you power up enough when light to see double digits on your GPS.

I made bunk boards but finally settled on KISS sleeping on the bottom with a boat cushion to feel the bailing well. And have settled on a tent made from a hammock shelter.

We did go up from a tapered 2 1/4 carbon mast to a 3 incher as we’d forgotton that you don’t want any bend in a lug rig, and have made a stepping box to make it easy to get mast up and down. I have straps set so I can carry the mast as a bowsprit when rowing, with same straps for the long oars when sailing.

Great info Ben, as I wondered about sleeping aboard this boat. In SoEast Mass & RI, sleeping aboard is mandatory for small boat overnight cruising.

Looks pretty close to ideal!

Who is the supplier for the carbon mast?

Tony deLima, proprietor of Forte Carbon Fiber in Ledyard, Connecticut, has been with RANTAN from the start, and built the mast she now has. He has also built carbon tubes for other luggers. They’re not cheap, but figure my sticks are now a couple of decades old; my original main is now the mizzen in a Jewel.