In November 2019, my husband Fredrik and I were looking for a small boat for a long expedition in remote areas of Alaska. We needed a boat we could row, sail, and beach. We began our search by visiting Gig Harbor Boat Works, where the Salish Voyager was still in the design stage. We rowed their Jersey Skiff, which has the same hull shape, and liked it. As we were about to leave, Falk Bock, the production manager, mentioned that a cruising version of the skiff, the Salish Voyager, was in the works and might fit our needs perfectly.

The Jersey Skiff and the Salish Voyager are both modern interpretations of boats from the late 1800s—small rowing and sailing vessels for fishing off the New Jersey shore. The story goes that these seaworthy little craft, which could be launched and recovered through the surf, were also used for rescuing shipwrecked sailors and salvaging their cargo.

Safety was the prime consideration in the design and building of what was to be an expedition boat. In August 2020, Hull #1 of the Salish Voyager had its first sea trial and became Gig Harbor Boat Works’ demonstration boat. Our boat is Hull #2.

In June 2021, we met our new boat in Haines, Alaska, and began putting it and ourselves through our paces. We did a 10-day shakedown before embarking on our 14-month, 1,500-mile maiden voyage.

The Voyager, built of hand-laid fiberglass and reinforced with a variety of core materials, was easy to load and unload from a trailer and, with a little practice, we could rig the boat with its simple balance lugsail, in 15 minutes.

We were able to roll the 440-lb boat above the high tide line by pushing it over two inflatable beach rollers—although three would have been easier. For steeper beaches, we rigged a system with a long rope and two pulleys set up with a three-to-one mechanical purchase. We were to be sailing in a region that has a 20′-plus tidal range, and it was critical to have a boat that could go dry conveniently in a variety of situations. Because the Voyager has a box keel, it rests upright on the beach. For extra protection on rocky beaches, we took advantage of the optional stainless-steel keel rub strips. Despite the relative ease of beaching, we discovered that anchoring off was even easier: on all but the stormiest of nights, we used 300′ of rope to create an outhaul system to hold the boat offshore while we camped.

When we boarded the unloaded boat for the first time, the initial stability felt a bit unnerving but, when we tried to capsize it, the secondary stability turned out to be amazing. Walking the gunwales was easy; tipping the boat over for capsize-recovery practice was not. I finally managed to capsize the boat by standing on a gunwale and pulling on the mast. The aluminum mast and boom are hollow and airtight and prevent the boat from turning turtle. The ample flotation in the hull’s multiple compartments ensure that the hull sits high in the water when on its side. Climbing onto the daggerboard allowed me to quickly right the boat. A rather non-athletic scissors kick brought me back on board over the side.

Our capsize practice was done in calm water with the boat unloaded, but it left me with a sense of confidence. The cockpit, which is self-bailing, didn’t take on much water. Pulling the plug in the recessed scupper let the majority of the water drain out. When loaded for an expedition, the boat would float considerably lower, and more water could remain in the cockpit. However, it would still float high enough to recover from a capsize with a manageable amount of bailing.

Photographs by Fredrik Norrsell

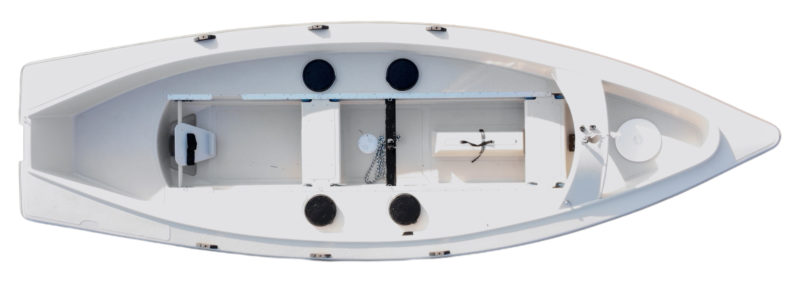

Photographs by Fredrik NorrsellWhen seen from above the ample storage and uncluttered cockpit are apparent. Storage beneath the side benches and foredeck is accessed via the large circular hatches. The cockpit’s raised floor keeps feet and gear dry. The aft sliding seat allows a second crewmember to either row while facing aft, or steer facing forward.

Our Salish Voyager carried everything we needed for well over six weeks at a time—food, camping gear, cameras, and an extensive collection of books, maps, fishing, and crabbing gear. The cruise-laden boat had the stability we needed to be able to stand up, change clothes, and move about the boat. This proved key to our comfort during our long journey.

The hatch in the cockpit floor gives access to a shallow compartment for storing extra fuel, canned goods, and beach rollers. The pry-out hatches on the side benches have a low profile and don’t interfere with seating. During this downwind run, the daggerboard is set forward of the mast and a plug is put into its trunk to keep water from splashing into the cockpit.

We had a round 10″ hatch in the bow, four 8″-diameter hatches on the side seats, and one long, shallow, 10″ × 20″ hatch in the floor that we used for extra fuel, canned goods, and beach rollers. Gig Harbor Boat Works offers several different hatch-cover types and arrangements. We were happy with the larger Beckson pry-out deck plates we chose for the side benches, because they were nearly flush and didn’t interrupt the seating surfaces as the raised flanges with rubber lids would. We installed a few tie-down points on the deck to help secure larger items, such as the tent, sleeping bags, and cooler.

When furled the sail, boom, and yard are raised above head height while the daggerboard is stowed forward of the mast. The bow and stern rowing stations have plenty of room between them but the rowers still have to focus on rowing in synch to avoid clashing oars.

The Salish Voyager has three sets of oarlocks and tracks on the parallel-sided benches support the sliding seats. The boat can be set up for either one rower in a center position or two rowers fore and aft. We didn’t experiment much with the center position as there were almost always two of us in the boat. Being able to keep moving while one person attended to making lunch, changing clothes, looking ahead on the chart, or simply taking a coffee break was helpful. If only one person was rowing, the forward position was the most powerful. When rowing, it was important to keep cadence with each other. If we were too far out of sync, we could—and did—occasionally clash oars. During our cruise, one of us could row at about 2 1⁄2 knots in calm water with a negligible current. The two of us together could row at 3 1⁄2 knots and keep it up all day. If wind or current were against us, having two rowers made the difference between hard work and attaining an enjoyable glide.

We always rowed with the mast in place and the bundled boom, yard, and sail suspended above head level and well out of the way. To minimize windage, we kept our bundle tidy and tight with four quick-release straps, but some weathercocking was inevitable. On one occasion we had the opportunity to row into a cave. It took us only ten minutes to remove the mast and sail and leave it on the beach. (It is not possible to row with the mast and/or the sail bundle inside the boat.)

Fully laden, the Voyager drew about 8″. As former kayakers, being able to row in shallow water close to shore was important to us. We were glad to discover that our minimal draft allowed us to maneuver around icebergs and through tricky reefs. For especially tight situations, one person looking forward and manning the tiller while the other rowed worked well.

The Salish Voyager is as suited to light breezes as it is to stiff blows. The single balance lugsail, generously sized at 100 sq ft, is easily rigged and controlled when singlehanded. The two sets of reefpoints allow the boat to be sailed comfortably as the wind pipes up.

With its 100 sq ft balance lugsail, the Salish Voyager performs well in a light wind. While we could often make way faster under oars than under sail, some days it just felt good to be lazy. One of my favorite ways of making way was “motorsailing.” With a mild headwind, one of us would take to the oars and the other the tiller. The oars felt exceptionally light as we flew along at 3 knots, about the same speed as if both people were rowing. Plus, with the extra speed the rowing provided, we could point higher upwind with the sail.

Over the course of two summers, we had about a 70/30 rowing-to-sailing split, which is considered good for our area. Our average sailing speed was between 3 and 4 knots. Top speeds were close to 5 knots, the theoretical hull speed.

The wineglass transom, deep skeg, and fine entry all enhance the Salish Voyager’s performance under oar. When sailing, the oars can be stowed up on the side decks, captured in their oarlocks. This keeps them both out of the way and also readily to hand if needed. Here the lugsail has its first reef tucked in.

The Salish Voyager has two sets of reefpoints, which allow for reducing the sail by 25 and 50 percent. This helped keep high winds from overpowering the boat. In a 10- to 15-knot tailwind, we sailed downwind in a following sea, double-reefed, at a manageable 4 1⁄2 knots. Both Fredrik and I are conservative by nature and reef early but even so, on a long trip it was inevitable that we would get caught out in winds that were stronger and gustier than we may have wished. At these times, we kept the sail tightly bundled. We put one person on the tiller and the other on the oars. Rowing provided more momentum than the bare mast could provide, and improved steerage, until we could find a lee or a safe haven.

When Gig Harbor Boat Works was designing the Salish Voyager they heard from several people who were looking for a beach cruiser that they could sleep aboard. For one person, sleeping aboard the Salish Voyager is easy, just lie down on the floor—there is 6′4″ of space between the daggerboard case and the aft bulkhead. As a couple, we experimented with making a platform at seat level. While this worked well and felt completely stable, we didn’t devise a good way to keep out the rain and bugs, so we chose to camp ashore in a tent.

In maritime endeavors we are kept safe by a balance of judgment, skill, and a good seaworthy vessel. The Salish Voyager proved a great choice for our expedition. It held up well in tough conditions for 14 months straight. It is a boat that a novice can handle, yet even after more than a year, I consider it a better sailer than I am a sailor. We can, and will, continue to grow into its capabilities for quite some time.![]()

Fredrik’s life as a nature photographer, and Nancy’s work as a writer and author of Riding Into the Heart of Patagonia, blend well together. They are currently working on the book Going Wild: A Summer of Paddling, Living, and Eating Wild. Small, self-propelled boats have always been part of their life as lifelong wilderness guides and outdoor educators.

Salish Voyager Particulars

[table]

Length/16′11″

Beam/5′7″

Displacement/440 lbs

Sail area/100 sq ft

[/table]

The Salish Voyager is available from Gig Harbor Boat Works for $11,495 for the rowing version, $17,495 for sailing. Many options are available.

The Salish Voyager is available from Gig Harbor Boat Works for $11,495 for the rowing version, $17,495 for sailing. Many options are available.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

…and how will we know when the book comes out? Perhaps SBM will print an excerpt?

Thanks for the rundown on the boat and how you used it. I look forward to the book when it is published.

I’m blown away you can pack for 6 weeks. Can you publish your stowage list?

I second the above question – Thanks!

My impressions of the boat mirror those in the article. The first time I boarded her the tenderness caught me off guard (and put on quite a show for the neighbors) but too much initial stability would make a her a poor row boat. Secondary stability is fine though.

The capsize recovery characteristics are much better than other designs I looked at and one of the main reasons for choosing her.

If you see one with a green stripe named Opium that’s us!

Interesting boat. And well sorted out. I like the double slides. I’ve had good luck in a similar smaller boat extending my mast and sail over the bow with some suitable straps as we often get an old swell with a calm that makes rowing with the mast up pretty miserable.

Let’s get to the important question, how was the fishing??

I was under the impression that the boat is self-bailing, but it sounds as if you had to sponge it out. Does it self-bail to some degree?

Yes, it is self bailing. I think their description of the capsize test with empty load vs full load is helpful. It will sit lower in the water when there’s six weeks of gear in storage.

Sounds like an amazing trip. Did I miss a link to a blog? Can’t wait to see more photos. Thanks for sharing.

Yes, Fredrik and Nancy have a great series of blog posts up here: https://ghboats.com/tag/wild-places/