Fifty years ago, the Maine Maritime Museum added a 16′ dory to its collection. It apparently had been brought from Massachusetts to Maine by a summer resident of Boothbay who rowed it for many summers. The dory probably had been built around 1900 somewhere on the North Shore of Massachusetts, the center of the state’s dory-building community. That area once provided thousands of slab-sided Banks dories for fishing schooners, and hundreds of “Swampscott” round-sided dories for inshore fishing and recreation. No builders or other documentation came to the museum with the boat, so it was dubbed a North Shore dory.

Ben Fuller

Ben FullerThe original 16′ dory from the North Shore of Massachusetts, circa 1900, is now on display at the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath, Maine.

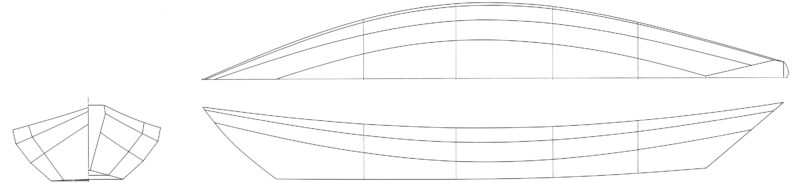

In shape, it marries the flat sides of the Banks fishing dory with the knuckles found on Swampscott dories: in the North Shore’s three strakes, the lower two have straight sections, with a knuckle in the frame at the bottom of the vertical sheerstrake.

The North Shore dory has details not found in working dories. There are beaded-edge floorboards in each section between the frames. Seat edges, inboard tops of each plank, and bottoms of the outboard planks are also beaded. The bottom has 3 1⁄2″-wide curved guard strips—called “shoes” on the drawings—beveled to meet the bottom edges of the garboards and running around the outboard edge of the bottom planking with a sturdy wide piece at each end. And it has stretched circular designs painted on each seat as well as on the removable seats at each end. These match the gray of the hull, whereas the sheerstrake and interior are white. This detail was not uncommon among recreational dories, as evidenced by several in the Mystic Seaport Museum collection, where the design’s color matches the sheerstrake. These designs may be pure decoration but also remind users to sit in the center of the boat.

Some features indicate that the dory may have been skidded into the water from a float or boathouse. There is no antifouling or other bottom paint, and the original paint inside and out is quite thin with no evidence of refinishing. The middle floorboard has worn paint. There are bits of sheet copper tacked to the base of the stem and sternpost, which would prevent wear when sliding off and onto a float.

David Dillion drew a fine set of North Shore dory plans for an article about dories in WoodenBoat No. 36, September/October 1980. The plans consist of two sheets and include lines, offsets, and construction details with a list of parts with wood types and dimensions. As part of an exhibit at the Peabody Museum (now the Peabody Essex Museum), a reconstruction of the North Shore dory was built as a hands-on demonstration. As far as I know, my dory, TIPSY, is the only other one that has been built to the plans.

About 2010, Kevin Carney, head boat instructor at the Apprenticeshop in Rockland, Maine, had some very wide pine planks with straight grain. Not wanting to waste them by cutting them into pieces, he deemed the planks perfect for replicating the North Shore dory. The challenge this dory poses is that its garboard is 16″ wide at the bow, requiring planks at least 24″ wide. When these are found, the ’Shop saves them for appropriate projects. The original had natural crook frames, which Kevin had replicated with riveted half-lap frames. Like the original, it is bronze fastened. The ’Shop built the boat on speculation, and after it was finished it spent a year or two gathering dust.

Ben Fuller

Ben FullerUnlike most working dories, the author’s North Shore dory has floorboards between the frames. He has removed the forward two panels, partly because he has found them unnecessary but also because it makes it easier to bail rainwater.

I needed a tender capable of carrying four or five crew for the Tancook whaler VERNON LANGILLE. The Apprenticeshop’s North Shore dory seemed like it would suit the purpose. We rigged it with tie-downs for the removable seats, thwarts, and floorboards so that they wouldn’t get lost in a capsize or a swamping. I added stringers under the thwarts to prevent them from flexing. As a tender, the dory didn’t do so well. It could take the weight easily but became uncomfortably unstable if the passengers rode on the seats in the bow and stern. They needed to be down on the floorboards. And, while the dory rows nicely from the stern and bow thwarts, a passenger on the center thwart keeps a bow rower from taking a full stroke.

I let go of the VERNON but I kept the dory, and row it in Camden Harbor in winter and in my cove on the St. George River in summer. With the launch ramp only 2 miles away, it often goes on a trailer for expeditions as far away as Mystic, Connecticut.

If I were building the dory as a trailer boat, I’d make the bottom and garboards of plywood. Indeed, plywood would make it possible to build this dory without access to wide pine. I’d keep the plywood as close as possible to the original scantlings, and I’d think about ’glassing the bottom and leaving off the shoes.

In the 10 years I’ve had the North Shore dory, I’ve learned a lot about it. With a waterline of about 13′, it’s hard to get it above 3 knots—it isn’t a race boat—but it’ll go all day just under 3. Without a skeg, it likes to turn. A pull on an oar can spin you past 90 degrees. This can be problematic in a crosswind but is a blessing when working the boat through a whitecapping chop.

While it is nice rowing on a flat calm day, where the dory shines is when conditions are a bit more demanding. As maneuverable as it is, it can easily work the waves in a chop. Going to windward, if the bow comes out of a crest over a trough and slaps down, the boat loses momentum. Rowing upwind, a little tacking helps prevent slapping and losing speed. Downwind in a breeze, I might row from the stern thwart and time my strokes to get little down-wave rides with each pull. Days when it is blowing 20 knots or so I call “half-boat days”: going to windward I aim to get a half boat length per stroke. On a course across the wind, a puff will catch the side of the dory and heel it a little.

The slab sides mean that the dory has less initial stability than a round-bottomed Swampscott or peapod. While you can kneel below the rubrail without taking on water, it isn’t especially stable when you’re moving about. This tippiness lets you steer some by leaning, with the dory turning away from the side you lean on. Rowing across wind on a windy day I can heel a bit to the windward or shift my weight a few inches to windward and hold a straight line.

Marti Wolfe

Marti WolfeThe dory trims well with a single rower aboard. Carrying a full water bag as adjustable ballast makes it possible to get the best boat trim for holding a course in windy conditions. A pair of 8′ oars works well when rowing amidships, allowing the hands to be comfortably separated and only slightly crossed when rowing in the forward station. However, at the aft station, where the oarlock span is narrower, 7′6″ oars are a better fit.

Trim ballast is an essential part to holding a straight course in a crosswind. I keep a full 5-gallon water bag, weighing about 40 lbs, in the bottom, which I can move forward or aft as needed to trim the boat to an appropriate angle to the wind. The bag in the stern, ahead of the tombstone transom, helps control nicely a tendency to turn into the wind—weathercocking—when the wind’s abeam. Sinking the stern with ballast raises the bow, letting it swing downwind. Then the stern acts a bit like a skeg. Going upwind, when I sometimes row from the forward thwart, I can control precisely how much bow is in the water, and the stern, with less weight, will swing downwind.

The dory works well with 8′ oars, used amidships with a hand span of space between handles or from the forward bench with a little overlap. The narrower span of the oarlocks at the stern station wants 7 1⁄2 footers, which are also useful with a shorter stroke when it’s rough and whitecapping makes it a little hard to get the oar blades out of the water.

With the notch for sculling in the tombstone transom, I can scull if I have a passenger forward or tuck the trim ballast right under the forward seat, as far forward as I can get it, to counter my weight in the stern.

Marti Wolfe

Marti WolfeThe working dories of the 1900s had no foot braces; instead, rowers pushed against the frames. The author added his own adjustable foot braces and a removable short sliding seat. Combined, these allow him to maintain a 3-knot speed even into a stiff headwind.

The original North Shore dory, like working dories of its time, had no foot braces; the frames served that purpose. I got tired of bracing against the frames, so I made some adjustable foot braces to attach to the floorboards, which make pulling much more powerful. What has really made a difference in rowing performance is adding a short sliding seat. It makes it easier to stay in the 3-knot range, but where it most helps is in my endurance and in being able to add power when rowing into a stiff headwind. It’s like having a second rower.

With its flat bottom, the dory is easy to trailer. I made a trailer-width shallow-V roller out of some PVC pipe which helps center the boat coming on. Beaching, of course, isn’t a problem, and if the tide has gone out, leaving the dory high and dry some distance to the water, the rocker in the bottom and the absence of a skeg make it easy to slip a roller or fender under the stern to facilitate getting back to the water. The oak shoes (rub strips) soak up the dings and dents, inevitable when landing on a rocky coast. In 10 years of serious use, I’ve not needed to replace the shoes and the garboard edges are unmarred. If I wanted better rowing performance, I’d take them off and replace them with a pair of straight bottom strips paralleling the 3″-wide strip secured to the centerline, which might help with tracking, but they wouldn’t protect the edges of the planks as well. A full false bottom, like that used on many dory types, would fully protect the garboards without increasing drag but would add to the weight of the boat.

John Williams

John WilliamsHaving a second rower certainly increases the power and speed but it also makes the dory less stable. To counteract this the author has added not only a 40-lb water bag, but also two 25-lb bags of shot. These can be moved around as needed for the perfect trim.

Lately, I’ve done some more rowing of the dory as a double. Two large people definitely make the dory feel unstable because the combined center of gravity of boat and crew goes higher. So, I’ve added more ballast. Besides the 40 lbs or so in my water bag, I set two 25-lb bags of shot in the bottom. Together, they have made the boat considerably stiffer and can fine-tune trim. It’s made me appreciate that heavily laden flat-sided dories shine when settled low in the water. The addition of ballast is really noticeable when pulling as a pair downwind in a breeze when the boat wants to dig its bow in and slew around into the wind.

The North Shore dory is solid as long as you stay low. I trust the dory’s stability and sea-keeping abilities enough to row year-round, though in winter I pick my days carefully. There are many fine light-wind days when there may be a big old swell running from a recent blow. The dory rides those like a duck. It’s easy to feel and look like the fisherman in his dory in Winslow Homer’s famous painting, The Fog Warning.

Is the North Shore dory for you? First, you have to like rowing. If you want more speed or only are out on relatively calm days, there are better boats. It isn’t great carrying a load of people unless you add ballast. Building the dory light with plywood would take care of the wide garboards, but the lighter construction wouldn’t add to the dory’s performance and indeed may increase the need for ballast. Adjusting the fore-and-aft trim makes a huge difference in performance when the breeze pipes up. It is a fine boat for big rollers. But if you like to dance with your boat, wiggle up and down through a chop, the North Shore dory is hard to beat.![]()

Ben Fuller, curator emeritus of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, has been messing about in small boats for a very long time. He is owned by a dozen or more boats ranging from an International Canoe to a færing.

North Shore Dory Particulars

[table]

Length/16′ 1 3⁄8″

Beam/4′ 3″

[/table]

Digital plans for the North Shore dory are sold by the Maine Maritime Museum for $20.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Thanks Ben! Nice article about these fine boats, and I like your suggestions about moveable ballast. I have a soft spot for dories, and had an Alpha-Beachcomber for 20 years that I sailed, but also rowed a lot (tough on very windy days!). It was built to the plans in John Gardner’s book and was also built as a demonstration in 1980 at the Peabody Museum by Lance Lee. I bought it from the original owner that had all the letters from when it was built. It was a wonderful boat that I sailed on Moosehead Lake and Muscongus Bay. Thanks for your article about dories!

We have the Hammond 16 Swampscott dory from John Gardner’s Dory Book and it’s perfect for picnics in Penobscot bay with our little family. Our two little ones sit side by side in the transom, my wife and I row from the forward and aft rowing stations, and the 50-lb dog (ballast(?)) sits between us. The dog moving about does shift the boat but we’ve never been nervous about the boat’s ability. It really shines in some chop!