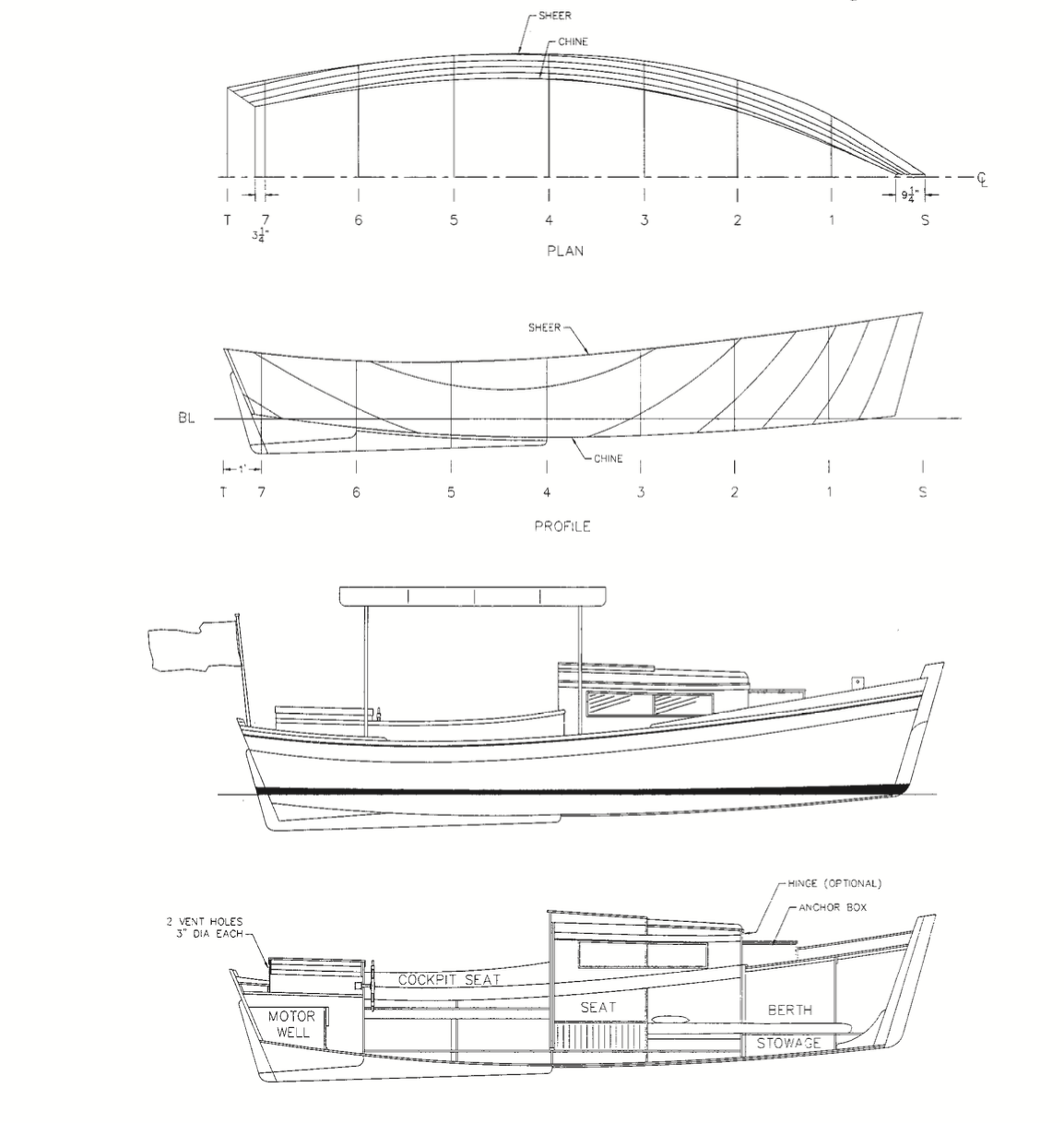

In the 1950s, Howard Chapelle drew an 18′ sharpie power skiff. He called her Campskiff. She was designed for the low-powered 5–10-hp outboard motors of the day and was intended to take her crew into the backwaters and creeks of the Eastern estuaries. For her hull planking, Chapelle called for 1⁄2″ cedar or mahogany. The bottom was planked with the same material, but was a full 7⁄ 8″ thick. For ward, the lines drawings show a full hull and a stem that just settles in at the waterline. Her proportions are nearly perfect.

Some 30 years later, designer Karl Stambaugh revisited the design, and the resulting Redwing captured the intent and all of the grace of the earlier sharpie. A close study of the two boats shows some well-thought-out improvements. With a LOA of 18′ 6″ and a beam of 6′ 6″, Redwing is bigger than Campskiff. She also has more freeboard and a finer entry. From any angle Redwing’s sheer is lovely, which is no easy feat for a flat-bottomed skiff. The house, motor well, and gracefully curved coaming complement the hull shape and add greatly to the boat’s appeal and function. The designer points out that Redwing is a light boat, 850 lbs, but she will carry heavy loads. With a motor, fuel, and batteries aft in the well and crew sprawled out in the cockpit, it will be necessary to place ballast forward, maybe several hundred pounds of it, depending on what gear is aboard, in order to trim the hull. The bottom of the stem should ride just below the waterline when the boat is at rest. Thus trimmed, handling in tight quarters even with a breeze up should be fine.

Photo by Bill Thomas

Photo by Bill ThomasKarl Stambaugh’s REDWING 18 is a plywood boat based on a Howard Chapelle design of traditional construction. Stambaugh designed his version “to make her easier to build while keeping the traditional appearance of the Chapelle design.”

Stambaugh’s Redwing is built of plywood. The first boats to this design were assembled “glue-and-screw” fashion; a “stitch-and-glue” version was later drawn. If you build stitch-and-glue, you might find the relatively quick assembly time and the bombproof filleted joints are worth the hassle of working with all that epoxy and filler. Once the hull is finished, the lion’s share of the remaining work is “traditional” plywood boat building. It’s fun stuff.

Marine-grade okoume is a near-perfect material for this type of hull. The boat’s sides are built of 12mm plywood and the bottom is created from two layers of the same material. The outside is sheathed in ’glass set in epoxy, and the results are strong and tight—just the thing needed for a cruiser that might live on a trailer. The side planks come together at a beefy, solid-wood stem. The house and deck, like the hull, are built from 12mm plywood. The deck is sheathed with Dynel cloth set in epoxy, but the weave is not filled. This makes for a strong, watertight finish that mimics the appearance of a canvas deck but requires little maintenance; and it won’t leak. The cockpit has wide seats curved to match the hull’s shape. These, coupled with high coamings, offer great comfort and space to spread out and relax while underway or tucked in for the night.

Photo by Bill Thomas

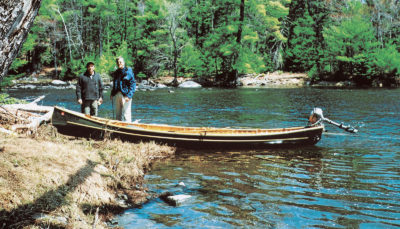

Photo by Bill ThomasRedwing might be the ultimate gunkholer. She’s designed for exploring thin and narrow waterways—places too tight for a sailboat to tack. At the end of the day, she provides ample camp-style accommodations.

Stambaugh has worked up a simple, electric propulsion system for Redwing. A small, stock 2-hp electric motor, the kind designed to be bolted to a cavitation plate, is mounted in the motorwell and driven by batteries stored forward, under the berth. With the exception of the custom-fabricated mounting bracket for the motor, all the components are off-the-shelf items. As configured, the range is about 40 miles at a leisurely 3 knots, which is a perfect speed for exploring creeks, small inland lakes, or quiet backwaters.

Most builders will probably choose to power Redwing with an outboard motor nestled in the sound-insulated motorwell. A 9.9 four-stroke is ideal, but a smaller engine will serve. One of the advantages of the 10-hp engine is that most come with electric start and a small trickle charge alternator. Steering harnesses that work with these engines are stock items, a real plus for the builder. At about two-thirds throttle, Redwing will move quietly though the water at 6+ knots and burn a half gallon of fuel per hour. On a boat as uncomplicated as Redwing, I’d keep the systems simple. A well-maintained outboard, one battery, running lights, and (just in case) an electric bilge pump are about all the complication Redwing or her crew should have to endure.

Photo by Bill Thomas

Photo by Bill ThomasDesigner Stambaugh estimates the materials cost for a Redwing 18 at about $5,000 (not including power). This figure assumes high-quality materials and finish.

Another place to avoid complication is with the cabin layout. There is a lot of room to get creative with the arrangements on an 18′ boat, but on Redwing there is room for a full-sized and comfortable V-berth, a head tucked under a seat, a fair-sized galley flat, and plenty of organized storage. Stambaugh has drawn a hard dodger for Redwing that blends in perfectly. It extends over the companionway and runs aft to the motorwell, fully sheltering the cockpit from rain and sun, without blocking the helmsman’s view or stifling the breeze while at anchor. As drawn, this awning complements the boat nicely, turns the cockpit into a living space, and can be removed easily and stored ashore if it’s not needed.

It’s the contemplated voyages in Redwing that really capture my imagination. Though designed for sheltered waters, she is capable of dealing with moderate wind and chop. Watch the weather and plan carefully and, as with any boat, be aware of her limitations. That said, I have seen Redwings along the coast of the Carolinas and on Georgia’s south coast, the Sacramento River Delta, and on Chesapeake Bay. I know of one being built in southern Maine, and I’ve seen one on Lake Michigan—trailered in from some landlocked state. The possibilities along the Florida coast alone seem limitless. Thanks in part to their shallow draft of 1′ 0″, these boats can and do get around.

Photo by Bill Thomas

Photo by Bill ThomasThe motor lives in an enclosed box, and is nearly silent. Cruising speed is about 6-9 knots, depending on choice of power.

Suitable cruising grounds abound, and if they lie far from home, a midsize car has plenty of muscle to get the boat, her gear, and her crew to the water. Redwing offers plenty of adventure in a manageable package. Keep the gear simple: a stove that can be used below on the galley flat or moved to a cockpit seat, a dishpan for a sink, and a cooler make a fine galley. I think I’d replace the V-berths with a large berth flat, which offers more sprawling room. When such a flat is outfitted with fold-up seat backs, it provides comfortable seating below. If you cruise in cool environments, there is room for a small wood heater to chase away any dampness and to boil the morning coffee. For adequate ventilation, there should be at least four opening ports in the cabin sides. Two small bronze opening ports mounted in the forward end of the house might also be welcome in warmer climates.

Photo by Bill Thomas

Photo by Bill ThomasAt only 850 lbs, Redwing is of an ideal weight to tow behind an average car. But she’s also capacious, and will carry a couple and their gear on an expedition.

Redwing works in so many ways. She is not a big boat, but she does offer the trailer-bound boater a literal (and littoral) world of options. She is economical to build and almost miserly in her fuel consumption. She is comfortable in a simple, uncomplicated way and easy to maintain. Owning a boat like Redwing would, I think, prove to be a joy and not a burden.

Plans for Redwing 18 include nine sheets, and the construction specifications include both glue-and-screw and stitch-and-glue. A full-sized frame plan is also available.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2008 and appears here as archival material. If you have more information about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Seems like the Redwing would make a perfectly fine small sailing craft; with the addition of a centerboard, and a mast step. Nice gaff or marconi rig with a correctly size jib. Perfect pocket cruiser? No?

Right, I had exactly the same thoughts. Would be a fine motor sailor.

As a life long sailor, these are the kinds of powerboats that appeal to me. No need to go fast, just a steady nice-and-easy, stately manner. I think if I were to build one, I would add a small folding windshield to the cabin top, there are times when blocking the breeze needs to be done.