If you are anywhere near the water, it has probably been hard to overlook the explosion in popularity of the stand-up paddleboard (SUP). Derived from surfboards, the larger and more stable SUP allows a paddler to stand in relative comfort and cruise along the water using a long paddle. Many wooden boat designers have taken notice and have answered the demand for good-looking, wooden SUPs.

My wife grew up inland and doesn’t have the deep affinity to the water and wooden boats that I do, but that changed one day a few summers ago when we rented some SUPs on a local river. She took to stand-up paddling with enthusiasm. It was fun, easy to learn, and offered an exciting way for her to get on the water; I saw a good opportunity for me to combine her interest in stand-up paddling with my passion for building wooden boats.

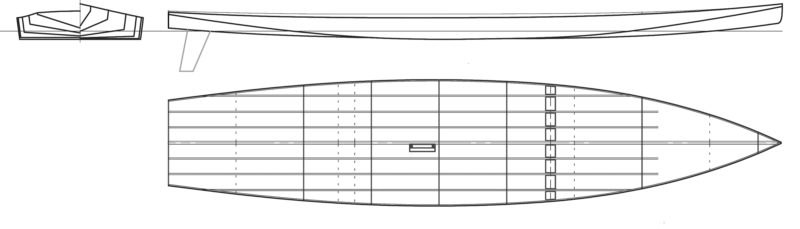

Right about this time, the Australian-born designer Michael Storer developed a wooden SUP and named it Taal after a lake near his home in the Philippines. The boats and canoes he designs are light yet strong, and while they may appear to look simple at first glance, they are actually sophisticated, elegant, and fast. His 12′ 6″ Taal is no exception. While many production SUPs resemble surfboards, they are rarely used for riding waves; they’re most often used on flat water. The Taal is designed like a displacement hull rather than a surfboard and optimized for speed, tracking, smoothness of ride, and stability on flat water.

I downloaded the PDF manual from Duckworks. It’s a comprehensive 72-page book with excellent instructions, color photos, and measured drawings. It is important to follow the plans exactly in order to achieve the boat Storer has designed. This build is more complex than most of his others and is not recommended for a first-time boatbuilder with no prior stitch-and-glue or epoxy experience. Precision in shaping the pieces and thorough epoxy application are the keys to a successful build. Dimensions in the manual are given in metric measurements—one millimeter is a finer measurement than the 1/16” mark on most tape measures.

The Taal requires three sheets of 3mm okoume plywood and some 8mm western red cedar. I was able to cut all the plywood parts out with a utility knife, as suggested in the instructions. The board is built a bit like an airplane wing with six bulkheads, a transom, and a longitudinal center plywood web that defines the shape of the board. A template for the deck camber assures that the tops of the frames all have the same curve. A second template, a half bulkhead, ensures uniform placement of stringer and deck-cleat notches.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonThe frames are concentrated in the board’s midsection where they support the paddler, leaving the ends and the overall weight light.

The deck, side, and bottom panels are drawn from the offsets in the plans, given at 400mm stations. The two pieces of each panel are joined with butt straps. The plans do offer advice for scarfing the plywood pieces together, but they state a preference for butt joints as they’re easier to align and have a cleaner appearance under varnish. The bulkheads are reinforced with 8mm-square cedar framing. The hull is stitched together using plastic zip-ties. The builder will go from a pile of small fiddly bits to a boat in the course of an afternoon. The deck is supported on 19mm x 8mm stringers that run longitudinally and rest on the cedar framing of the bulkheads. Weight is then transferred to two long stringers that run along the bottom of the board. I followed the plans include instructions for installing a commercial fin box and made a fin to fit it.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonThe vertical cutwater and the sharp V sections forward eliminate the slapping that surfboard-style paddle boards are subject to.

One fun task is using a shop-made “torture board,” Storer’s term for a flexible fairing board, to sand the support stringers to meet the deck’s graceful curve. The booklet gives both very detailed instructions for using the torture board and a template for the deck’s curve so the builder can get the stringers beveled just right.

A layer of 150 gsm (4.42-ounce) fiberglass is laid underneath the main walking area of the SUP deck which stiffens the deck considerably in this area. The deck is glued onto the hull with packing tape and a few well-placed weights. For me it was a two-person job. Be sure to watch for the slight compound curve in the forward 800mm where the crowned deck takes an upward curve to the bow.

There are a few challenges, such as placing the fin box or using a temporary bulkhead to get the correct dimensions and shape for the bow, but this is part of the pleasure of building wooden craft. I found the build to be immensely enjoyable and satisfying work.

Allison Grappone

Allison GrapponeThe carry handle is offset to starboard, and taller paddlers with long arms would carry the board with the greater part of the beam under their arms. A paddler with shorter arms would carry the Taal flipped over to put the handle on the high side.

My Taal came to 30 lbs. I think I might be able to make the whole board lighter next time if I took extra care to use only an amount of glue that is strictly necessary. While I also bought a rubber nonskid adhesive mat to stand on, Storer offers instructions for making an anti-skid area by applying a coat of varnish with sugar sprinkled on it, letting the varnish cure, and then dissolving the sugar with water. That approach could be a few ounces lighter than a mat.

The handle insert is set off-center, providing a comfortable carry for long-armed paddlers on one side and short-armed paddlers on the other. I located the handle on my Taal a bit forward of the board’s center of gravity so that it would carry slightly bow high, which I find easier to handle than a bow-down board. The hard 90-degree chines make long carries slightly irritating, but this is easily alleviated with a towel draped over the board to cushion the edges.

Allison Grappone

Allison GrapponeThe author has plenty of freeboard. The Taal is designed to carry up to 250 lbs.

Once on the water the Taal shows its strengths and design pedigree. It is fast, stable, light, and tracks true. It is important to figure out where to stand to get the correct trim because, as with a rowboat, you do not want to drag the transom. A spotter looking at the board as you move fore and aft can help with this. The trick is to be forward enough to clear the stern but to stay within the reinforced section of the deck. The Taal eats boat wakes without drama when taken head-on. The knife-like stem cleaves the wave, the bow buries but the full body shape immediately lifts the SUP back up and over the wave with a surprising amount of ease. There is no slapping as there is with surfboard-shaped boards. The Taal has excellent initial and secondary stability for a SUP. Getting on the board requires standing in the center and pushing off. There is initially a bit of wobble until the paddler gets situated, and then they Taal settles into a very solid ride with no surprises. The board inspires confidence and the paddler can focus on the stroke and the paddle rather than the task of staying right side up.

Allison Grappone

Allison GrapponeThe flat bottom amidships transitions to a V cross section at both ends. The ample rocker brings the transom out of the water to minimize drag. The elevated chine adds stability when the board is heeled.

The Taal is really designed for tracking straight and covering distance while cruising. You can make course adjustments easily, but it takes some effort to turn the Taal smartly around. For a tight turns, you’ll need to use the SUP pivot turning technique, stepping back on the board to sink the stern and raise the bow. There will be a distinct wobble with every step, but the secondary stability will kick in before you’ll get thrown off. When the pivot turn is performed correctly, the Taal will then execute a 180-degree turn in its own length. When walking the board to change trim, it is important to remember that the forward and stern sections of the deck outside the center four bulkheads are only lightly reinforced, so walking the full length of the deck is not recommended.

Storer limits the Taal carrying capacity at 250 lbs. My wife and I both got aboard one day and paddled across a lake, and found we still had freeboard with our combined 280 lbs.

Everyone who has paddled our Taal has been impressed with its speed and stability. It’s a luxurious platform to paddle on, and it also looks gorgeous on the water. With the gentle curve of the deck meeting the distinctive transom, the sharp stem, and that classic look of wood, the Taal exudes style.

This is our second full season on the Taal, and we are completely satisfied with its performance. When my brother and I visit our parents in Connecticut, we like to cruise out into the local harbor on our SUPs and check out the boats at mooring which pique our fancy. When I’m home in New Hampshire I’ll meander with the Taal around the local rivers and lakes. My wife loves to paddle out 100 yards from shore with a book, lie down, and sunbathe high and dry with little fear of falling off. The Taal is her own private beach floating in a lake surrounded by the green hills of New Hampshire.![]()

Christophe Matson currently lives in New Hampshire. At a very young age he disobeyed his father and rowed the neighbor’s Dyer Dhow across the Connecticut River to the strange new lands on the other side. Ever since he has been hooked on the idea that a small boat offers the most freedom.

Taal Particulars

Length: 12′6″

Beam: 30″

Weight: 18lbs to 31lbs depending on materials

Crew capacity: 150lbs to 250lbs

The Taal was produced by Storer Boat Plans. Plans are available from Duckworks for $80 (file download) or $105 (printed).

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Nice boat. Very similar dimensions to the Alcort Standard Sailfish. Adding a sailing rig next? 🙂

Cheers

Kent

What would you estimate the cost of high-quality materials? Quality plywood, quality epoxy, etc.

I don’t want to put a hard and firm number on this as location and conservative use of materials can differ from build to build, but from my personal experience in New England I would say a budget of $500 would be sufficient for this design for materials needed (no tools), give or take $100. Around here I can get 3mm okoume plywood for about $55 USD a sheet, and TAAL takes 3 sheets. If you coat the board, it takes about 6 liters/1.5 gallons of epoxy, and depending on the epoxy and amount you choose that’s another $100. I used a UV-resistant epoxy so I didn’t have to varnish over the epoxy coating. This kept the weight down and also reduced the amount of work. It looks great two years later with the board stored outside, uncovered, in a protected place. UV epoxy is slightly more expensive, but then there are no costs for UV-blocking varnish. A roll of fiberglass tape isn’t much, and neither is the commercial fin or finbox. Unfortunately I don’t have an accurate answer in terms of the western red cedar (other woods that he species may be used), I had some leftover from a previous project and used that, but it doesn’t take much overall. A few longer 1×4 boards will be plenty. Throw in an SUP paddle and away you go!

I feel it is important to note for other readers that it’s imperative to build the TAAL, or any of Mik Storer’s lighter weight high-performance designs, with the materials he specifies. Building a TAAL with anything other than 3mm Okoume and marine epoxy is going to create an inferior boat for minimal financial gain. Storer is very clear about this in his plans and I strongly agree.

I find a large windproof golf umbrella makes an excellent sail—instant deployment with a nice whomp like a small spinnaker. With the paddle well aft as a rudder, one can sail 90 degrees off the wind. A fun reach. Sit down over 15 to 20 knots. good for shade and rain too. $25 on Amazon

Nice build! Can you tell us specifically the epoxy you used? I like the idea of UV epoxy very much. And where did you source the fin box?

Plan has a DIY fin box plus instructions to use a standard commercial box.

I think now I’d use something like a dagger board box. Pull up fin to release weed. Or even take fin out completely to cross heavy weed.

I need to make a boat like this but using cedar in a bead-and-cove construction. I realize the boat may become heavier, but if I am smart in epoxy use I would hope the strength would be there for my saltwater needs here to fish from it in salt water. I welcome your comments.

Thank you,

Terry

I have never seen the true usefullness of these except an exponent of the the latest component of the latest fad. The surf-ski kayak fad of the ’80s was more more useful and practical.