I was 17 in the spring of 2020 when I decided that I would build my first wooden sailboat. I had two major criteria for this summer vacation project: the boat had to be small enough to build and store in my garage, and it could cost no more than $1,000. I also hoped the boat would comfortably fit two adults, be easy to trailer, and serve as a light daysailer on protected waters, with oars as the auxiliary power.

After reading a set of books loaned from a local boatbuilder, I decided on the 15-1/2′ Surf Crabskiff. Phil Bolger designed it as part of his first line of Instant Boats, and his intention was to create a design that a novice could build as a first boat. He began with his Elegant Punt design and extended its lines forward beyond the bow transom to a raked stem, and aft beyond the stern to a narrow, dory-style tombstone transom. The result, a 16′ cat-rigged sharpie, performs well under sail and oars, and can be built inexpensively by a complete beginner. The Surf was just what I was looking for, and I ordered the plans.

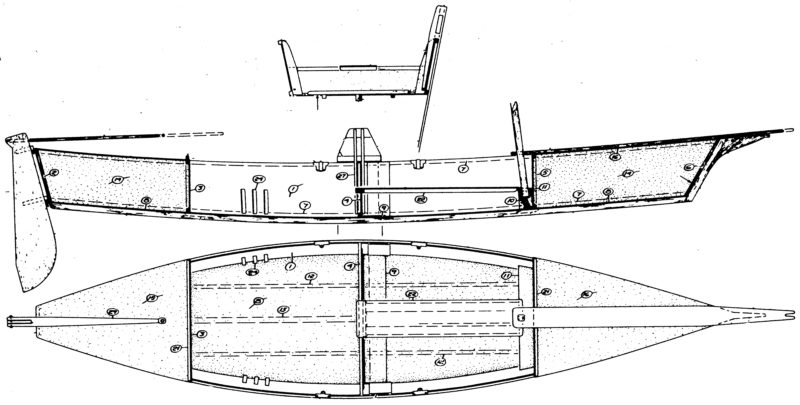

The plan set includes two 22″ x 34″ pages of drawings, and three pages of typed instructions, which are very explicit. Dynamite Payson’s book, Instant Boats, includes a step-by-step description of how to build a boat very similar to the Surf. There are also photographs of each step of the process—helpful for those of us who are just learning the vocabulary of boatbuilding.

The hull is designed for simplified chine-log construction, which eliminates the necessity for a strongback or jig. All the plywood parts except the rudder fit onto just four 4′ x 8′ sheets of 1/4″ plywood. The plans state that “marine grade” is preferred, but that high-quality exterior-grade plywood will serve. I used marine-grade okoume. For the lumber, the plans call for “almost any timber hard enough to hold nails and not too oily, acidic, etc. to hold glue.” I bought a single 10′ x 3/4″ x 12″ clear pine board, four SPF 2x4s, and used old, maple shelves for the rest. The small amount of wood, combined with the minimal epoxy compared to other types of construction, allows for economical construction, even with premium materials.

William Skelly

William SkellyThe external chines are quick to install and easy to bevel to accept the bottom panel.

The construction predates the shift Payson made to tack-and-tape in his later Instant Boat books, but I found it even more straightforward. The chine logs are external, making them exceptionally easy to install and then bevel to accept the bottom panel. All of the bevels in the boat are constant, not rolling, so they are easy to shape, and the epoxied joints between plywood pieces are reinforced with pine framing, eliminating the messy job of applying filets and fiberglass to the intersections.

The Surf has two large flotation tanks—one in the bow and the other in the stern—which were designed to be fully enclosed by the decks and bulkheads. To put these spaces to good use, I installed watertight hatches. I installed a pair of 8″ deck plates in the foredeck and made a rectangular wooden hatch for the aft deck. I store a manual bilge pump, anchor, line, and other small items in the forward compartment; the aft compartment is large enough to fit a cooler. I also did away with the decorative gammon knee and bowsprit. The sailing rig doesn’t require them and they would have made the boat too long to fit in my garage.

I started my Surf in June 2020 and finished in November, working many full days during the summer, and otherwise on evenings and weekends. I went a tad over budget (I could have come under my projected $1,000 if I’d bought the inexpensive materials recommended in Instant Boats, but I opted for better plywood, a pricy two-part primer, and bronze fasteners throughout). The materials for the boat, including epoxy and hardware, cost me about $1,200.

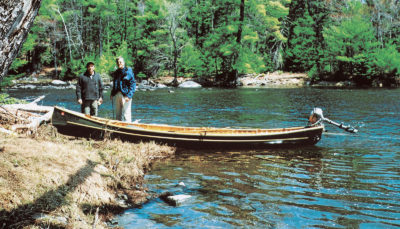

The bare hull weighs in at about 120 lbs, so you might be able to cartop a Surf, but I built a trailer for mine. Since the boat is so light, even a small car will find it easy to tow, and two people can carry it from the trailer to the water, eliminating the challenge (for me at least) of backing the trailer into the water. To launch, I simply pull up next to the ramp and have a partner help me carry the hull to the water.

Tom Nallen Jr

Tom Nallen JrThe rudder, as designed, has a fixed blade, and can only be shipped when there’s water deep enough for it. Making the rudder with a kick-up blade will ease beach launches.

Stepping the mast, with the sail furled around it, is easy alongside a dock or at the water’s edge with the bow resting on the beach. The fixed-blade rudder, however, cannot be mounted at the beach. After I step the mast and put the gear in the boat, I row to deeper water where I can ship the rudder. The transom is so far from the cockpit that it’s a sprawl across the aft deck to attach the rudder. If you are planning for beach launches and landings, make the rudder with a kick-up blade. I am currently modifying a weighted kick-up rudder to fit my transom hardware. There is a single, fully removable leeboard that slips over the side amidships; it frees up space in the cockpit that would otherwise be taken up by a daggerboard trunk.

There is ample room for two adults. The cockpit is divided into two sections, with the ’midship frame and its half bulkhead as a partition. To sail, the occupants sit on the bottom of the boat, one in each partition. Moving from one side of the cockpit to the other, while tacking, is merely a matter of shifting one’s weight because of the narrow beam. The Surf is exceptionally stable, and I have been able to keep mine level even in a 15-knot wind with just one of the two occupants hiked out. The ride is dry, pushing through motorboat wakes at hull speed.

The Surf is a joy to sail. The plans call for a sheet that goes straight from the end of the boom to the skipper’s hand, but to ease the strain of holding it, I use a one-part tackle with the sheet led through a block on the boom end and eye-spliced to a brass swivel, which is clipped to a rope traveler. While the traveler limits the tiller to an overall arc of 60 degrees, I have found that’s plenty. With its light weight and rocker, the Surf responds instantly to the helm. Because the boat is so light, it doesn’t carry much way when tacking, so to avoid getting caught in irons, I bear off to pick up speed before coming about. When tacking, I choose to leave the leeboard in place instead of shifting it to the leeward side. The difference in performance is negligible, and it simplifies tacking.

Downwind, the sprit boom keeps the sail flat, and lifting the leeboard off the gunwale and bringing it inboard helps to pick up some speed. Head-to-head against a Sunfish, the Surf (with a passenger) outperformed the solo-sailed Sunfish both upwind and downwind.

Tom Nallen Jr

Tom Nallen JrThe sprit boom sits high above the heads of the seated crew, so it won’t hurt anyone during an unexpected jibe. The leeboard slips over the rail and in moderate breezes does just as well set to windward as to leeward.

The leg-o’-mutton sprit sail has only two controlling lines—the sheet and the boom’s snotter—which makes sailing the Surf very simple and fairly safe. The sprit boom stays above the heads of the crew while coming about. Even in 17 knots of wind, the only punishment for an uncontrolled jibe is a slap from some sailcloth. The tack is secured low, very close to the foredeck, so the foot of the sail obscures the view forward. My sail has a “window” to help me see what’s ahead. While the drawings for the sail do not include reefpoints, the unstayed wooden mast bends and spills air if there is too much wind. I estimate 15 knots is the border of what is too much wind for the Surf. I once went out in 17 knots, but felt that was pushing it. To furl while afloat, I undo the sprit, and bundle the sail around the mast. Held by a few sail-ties, this arrangement keeps the windage down enough to row back to the launching point.

George Skelly

George SkellyFor rowing while at the aft station, sets of cleats fastened to the sides of the boat provide a purchase for the feet. For a bit more power a footboard could be installed between the cleats on either side.

For rowing, there is a removable fore-and-aft bench for the forward compartment. There are two pairs of oarlocks: one aft for rowing without a passenger aboard and another forward to balance a guest sitting in the stern. The standard formula for oar length indicates 6′ 9″oars would be the match for the boat’s 41″ beam; the 7′ oars I’ve used have buttons on the leathers that make for a bit of extra overlap at the handles. That required a hand-over-hand rowing style I wasn’t yet used to. The Surf turns easily and carries its way well after each stroke, even against the wind. After gliding for about 1.5 boat lengths, the Surf would start to veer, but as long as I kept rowing and paid attention I could make the boat go straight. Putting a bit of weight in the stern should improve the tacking. I will note that I am not necessarily a good judge of rowing performance, and the only other boats I have rowed in my life were either rubber dinghies or fiberglass rectangles. In comparison to those boats, the Surf rowed wonderfully. It felt much easier, even though I have yet to get used to hand-over-hand rowing. I primarily sail my Surf, so all I personally need in terms of rowing performance is enough to get me back to the beach if the wind dies. The Surf exceeds this requirement.

George Skelly

George SkellyThe plans call for a rower’s bench that runs fore and aft along the centerline, making it easy to switch between the rowing stations while remaining seated.

Although I have only sailed my Surf, christened COURAGE, for one season, the boat has already given me many adventures. Its performance suits my purpose nicely, but the Surf’s strongest point is that it is not demanding to own. A sailboat doesn’t have to trap you with yacht-club fees, endless maintenance, or a hefty price tag. The Surf is a boat that a novice, like myself, can build with little prior knowledge, then say, “Let’s go sailing,” hop in the car, and head off to another adventure. No fuss, no fees, just wind and water, wood and sailcloth.![]()

William Skelly is an 18-year-old high-school student who lives in Carlisle, Massachusetts. He has been sailing since he was 14 when he took a “Learn to Sail” course on the Charles River at Community Boating in Boston. He has since continued his sailing education at Community Boating and elsewhere, and sails during the summers and on weekends during the sailing season.

Surf Crabskiff particulars

[table]

Length/15′ 6″

Beam/3′ 7″

Sail Area/59 sq. ft.

[/table]

Plans for the Surf Crabskiff are available from H.H. Payson & Company for $45. Harold “Dynamite” Payson’s Instant Boats, which details the type of construction used in the Surf, was published in 1979 and is out of print, though copies are available on the web. Payson’s Build the New Instant Boats has been in print since 2010, but it is an introduction to tack-and-tape construction, not the fasteners-and-glue approach used for the Surf.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Excellent article, thank you 🙂 (sweet boat, too!)

Thank you for kind comment. I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

Extremely well written! Nice job on the article and thanks for taking the time to write it. The boat looks fun too…

Great fun boat. Built one about 1970.Floated away one night during storm surge. Thinking of building another with the kick-up rudder as mentioned

and a couple bilge boards built into the sides. Will use my canoe-yawl sailing rig.

Thank you for kind comment. I’m glad you enjoyed the article. The Surf is definitely a fun boat.

Great article and fine looking boat! One question: doesn’t it get fatiguing holding onto the sail all the time? Would it be possible to put a cleat somewhere to give your hand a break, or is the boat too lively for it?

Thank you for the comment. I personally haven’t gotten fatigued from holding the mainsheet for several hours straight. The load isn’t huge unless the wind is strong. I have considered adding a couple of cleats, but I sail in places where the wind is shifty, so I like to be holding the mainsheet at all times. You could probably add some jam cleats and do fine as long as you steer to the sail.

A lad that can compose a paragraph. You give me hope for the world. I have always been intrigued and skeptical of Bolger’s designs, so I built two to find out for myself. Both—Clam Skiff and Reuben’s Nymph—perform far better than I hoped. Thanks for the write-up.

Thank you for the kind comment. Phil Bolger seems to have had a talent for designing boats that perform better than their looks alone suggest.

Excellent article and boat, thank you. My copy of Instant Boats is a long-time resident of the shelf in my bathroom :-)…

Any details or photos of the trailer?

Thank you for the comment. For freshwater, I borrowed a Lowe’s mesh wire “utility trailer” and attached bunks using U-bolts and lashings. For saltwater, I made a trailer out of parts from an old, galvanized, 420 trailer a friend was looking to get rid of. On a flat-bottom boat with rocker (e.g. the Surf), the bunks should go side to side, not front to back. The bunks also need notches for the bottom skids and rowing shoe. For bunks, I used two 2x4s on their ends. I can email you some photos if you are interested. The trailer I built looks something like this one:

Very nice writing and extraordinary photos, thanks! I built the Surf in about 1986, bright sides and brick bottom paint with cream colored paint inside. It was spectacular, even with the exterior grade plywood I used. (I might choose differently now.) Sailed in Humbolt Bay in No. California, extremely enjoyable. Then I moved away from water, and the boat hung in various garages for years, hoping for use. Finally, for my last longish move, I decided I would gift the boat to the Girl Scouts – but one of my sons pre-empted that idea. He bought a trailer and took it home. It eventually sustained some storage damage, and my son took it to a boat shop on Puget Sound and had it restored. The interesting part is, it now looks very much like yours, white with blue: